A Dartmouth Response: Project ABC, Now in Its Fifth Year

Dean of the Tucker Foundation

Inever felt that I was the angry, youngBlack. But I am Black, young, and veryangry and frustrated. I am angry because1700 Blacks live on one half of acity block, because 12-year-olds carryknives and pimp for their 16-year-old sisters.I am angry because my Harlem cousinsthink that all fathers only come for visitsif they exist, that all parents drink incessantly. . . and that all grandmothers workas domestics when they are 78 years old.

I am angry because my uncle died yesterdayin a filthy hospital for Blacks inLake City, South Carolina. He died becauseof a clogged catherizer and because thereare four nurses for 256 patients and nobodycould check the equipment.

Most of all I am angry because for mostthere is no hope or will to survive, and formost there is only the myth of God, mythof mercy, and fear. - ABC student.

In North Andover, Massachusetts, it was formerly a private home; in Amherst, a nursery school; in Andover, a Phillips Academy house; in Appleton, Wisconsin, a college dormitory; in White River Junction, Vermont, a rooming house; in Northfield, Minnesota, a private residence; in Lebanon, New Hampshire, private apartments; in Hanover, a faculty residence. Although their histories are richly diverse, these eight large private houses, stretching over 1500 miles of American landscape, share a common bond - each has been purchased or leased by a group of citizens in a public school community for use as an ABC (A Better Chance) residence.

The eight residences are interesting because collectively they house, feed and educate over 100 people each day. They are important in that each represents the effort of a group of citizens, acting privately and without fanfare, to make the public school in their community available to promising youngsters who, without such a chance, might be trapped permanently by poverty and all its attendant erosions.

- beds being made, drawers and doors in motion, breakfasts bolted, lunches packed, hasty exits with armloads of books. Each has steady traffic - Board members keeping in touch, dinner guests, high school friends, host families picking up students for weekend visits, college undergraduates arriving to provide tutoring; the serviceman, the cook, the cleaner. Each has evening quiet - study from seven to ten. Each is home for ten ABC students, two college tutors, and an experienced secondary school teacher (the resident-director) and his family. Each residence has morning commotion

Why did we create a program under one roof rather than place ABC students with individual families? Certainly the residence makes it more difficult to weave students into the community and we run the risk of having the residence labeled or stigmatized. We weighed these drawbacks against the advantages of a single residence and its opportunities for preserving ingredients which seemed so important to ABC's early success: close association with an experienced teacherhousemaster, easy identification with college-age tutors living in the residence, opportunity for ABC students to support one another, and a living-eating-studying climate conductive to sustaining an urgency about program objectives.

But perhaps more important than any of these reasons was our concern that ABC students continue to be themselves. Assimilation into a white family or a white community was not our objective. We wanted to protect and preserve the many special qualities that the students brought with them. We wanted to foster confidence in themselves and a strong self-image. We wanted, in every way possible, to increase their understanding of social problems, to develop their capacity to deal with these problems, and to reinforce their determination to invest their own lives in bringing about positive social change. The residence, which demands constant interaction among the director's family, undergraduates, and ABC students, makes these objectives realistic.

In many respects these public school residences are not unlike dormitories at the more than 100 independent secondary schools which, in five years, have enrolled 1100 ABC students. And, given its generous national publicity and rapid expansion, ABC might well have remained exclusively within the independent schools. The success of the students from 1964 on attracted new private schools, new colleges to provide the summer transition (Mount Holyoke, Williams, Carleton, and Duke) and new financial support. Nevertheless, those of us close to this effort were acutely aware that ABC, as originally conceived, was severely limited by both the physical capacity and the financial resources of the private schools.

The total enrollment in ABC preparatory schools is 25,000. Most have Negro enrollments well below 5%. Even if they make steady gains in the years ahead, perhaps to a 10% level, the total places for ABC-type youngsters will be only 2500. Considering the magnitude of the problem nationally, a scholarship umbrella for 2500 students can hardly qualify as more than a very selective initiative quite outside the thrust, in numbers and intensity, of the revolution necessary to achieve equal educational opportunity for every youngster in our society. Furthermore, in that ABC annually was turning down hundreds of equally qualified applicants it was imperative that we find new opportunities.

Increasingly we asked whether it would not be possible to extend ABC to public schools across the nation which were not now serving broad socio-economic groups. Might not these schools serve as an enormous resource for equalizing educational opportunity? Selecting one (and the nearest) to test this theory, in September 1966 we launched ABC in Hanover High School.

From Georgia, Alabama, Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, ABC students came to Hanover by a route identical to that used for hundreds of ABC students previously enrolled in preparatory schools. They were chosen by a Hanover-Norwich Committee from among those identified and recruited by the Independent Schools Talent Search. We made use of the Talent Search administrative machinery, field experience, and network of resource persons living in urban and rural ghettos throughout the country. The same criteria used to identify private school applicants - economic hardship, academic potential, motivation, and limited educational opportunity were used to select the Hanover High School ABC students.

Although the focus of ABC continues to be preparation for college and, ultimately, for leadership roles in society, we continue to search for genuine "risks" those students who, if not offered an educational alternative, most probably will be lost to the leadership sector of our society. And we continue to reject apparent "winners." Applicants judged capable of "making it" without the ABC opportunity receive a letter explaining that ABC scholarships must be limited to those who appear to have greater need.

Making such distinctions is obviously difficult. We work with imperfect evidence and the knowledge that only through sustained interaction with a student can a teacher fully appreciate the range and depth of his talents as well as his limitations. Watching a so-called "winner" from a Southern Negro high school fail successive English theme assignments does, however, make one aware of the extent to which "risk" is a relative term.

During the first two years of the Hanover program, ABC students made steady progress in rigorous college preparatory courses. Five of the ten made honor roll; A and B achievement is the expected level of performance. Of the three ABC students who graduated from Hanover High School in June, one is enrolled at Duke University and two at Dartmouth.

ABC life is not all study, although it is fair to say that these students are expected to work harder than most of their contemporaries. Eight of the ten play on the school's athletic teams, one is very much involved in art, one in drama, and two in music. One serves on the Teen Canteen student board, another on the Youth Fellowship Board; one was recommended for All-State Band, another became a semi-finalist in the New Hampshire-wide election for youth Governor.

Perhaps more important than grades, activities or awards is the simple fact that these young people have experienced an educational alternative. Only in this way will they develop broader perspectives. Only in this way will they begin to understand the possibilities for change. Perhaps most revealing are the comments of a student from Georgia: "ABC has put many doors in front of me," he said. "The doors are not yet open but for the first time in my life, the doorknobs are within reach." He believes that he is developing both the competence and the will to influence directly future events for his people both in Georgia and beyond.

We believe that ABC has been no less important to local high school students. The following yearbook comments, written by classmates of a graduating ABC student, suggest that Hanover-Norwich students also have much to learn about their society:

"Though I don't really know you well, I like your quiet way. You seem to know what you want and I hope you will always get it. You have a sincere feeling for the good of all mankind. I think it is very admirable, _______, and wish the best in everything you do for your fellow citizens."

"I can truly say that meeting and knowing you has been an experience for me. I have learned many things. A clue to understanding is knowing someone like you...."

"... one of the most wonderful persons I know. Thanks for all you have done for me. It is more than you know."

"You may not believe it, but I have enjoyed knowing you more than anyone else this year. You have really changed my way of thinking about a lot of things. I could never thank you enough."

And the community has benefited. Whether the interaction occurs in the home of a host family, at Teen Canteen, on Main Street or in a dentist's chair, the community is heavily involved and will identify with ABC's successes and failures.

Our concern for what this program might do for ABC students, local high school students, and the community is surpassed only by our concern for what it may do to change those conditions which now make ABC necessary. This effort will be successful only as its graduates, beyond college, are determined to serve their people. Permanent change must be brought about by those from within using their experiences from without. The outside experience must prepare them for leadership and reinforce their determination to exercise that leadership with and through their people. That is the ultimate goal of ABC.

The public school ABC idea was conceived as a community enterprise - not a college or a private school initiative, but a community effort. But could this idea - tested and proven in a college community - work equally well in a town without 3000 undergraduates? Could it take hold in a community which would see ABC as something new? To answer these questions, The Rockefeller Foundation made a three-year grant to enable Dartmouth to test ABC in a second public school community.

The Hanover ABC resident-director, Tom Mikula, was familiar with the town of Andover, Mass., from his teaching days at Phillips Academy. He was aware of the concern exhibited by its citizens for the quality of its schools and he knew of a men's group at West Parish Church who were tired of "chicken-dinner brotherhood" and were searching for a meaningful program of social action. The West Parish Fishermen were impressed by the ABC story - both the need and the promise. It seemed to be precisely the project for which they had been searching. It was obvious, however, that ABC was an undertaking that would require help from the entire community and the base of support was therefore broadened to other Andover churches.

There were problems that delayed a quick acceptance of ABC — an overcrowded high school, a new building whose completion was rumored to be delayed, a stirring of unrest because of rising costs. The ABC committee worked conscientiously with school officials and with school committee members for a favorable hearing.

There followed a series of public meetings and panel discussions. Members of the committee fanned out to neighborhoods to answer the many questions regarding legal, social and educational aspects of the program. A brochure was mailed to all registered voters. Local and Boston newspapers reported the issue fully. By March, town meeting time, the issue was in the hands of the citizens of Andover. By a vote of 528 to 119 they launched the program.

Suitable housing was located, students were selected, and a resident-director was found from the Andover High School faculty. Two Dartmouth students were selected to live in the residence and teach in the high school. As in the case of the Hanover resident-tutors, these undergraduates continued to be full-time students at Dartmouth, receiving three course credits for their teaching.

Sixty Dartmouth students have lived with and assumed responsibility for ABC students either during the summer or during the academic year in one of the public school residences. In choosing undergraduates to work with ABC we have searched especially for those who show promise of relating easily and well to teenagers, those who are disciplined intellectually and in personal behavior, and those who are prepared to invest themselves fully in other human beings without being unrealistic or overly ambitious about the possibilities for human change.

We have not searched for those undergraduates with a prior commitment to education or social work. Rather, we see ABC as an important vehicle for exposing large numbers of undergraduates to social problems with the conviction that this is a terribly important ingredient in their preparation for future responsibility, be it in business, the arts, the professions or government service.

Frequently I am asked whether these undergraduates are typical. Sometimes implied in the question is the suspicion that a large percentage might be drawn from the more radical or far-out under-graduate constituencies. This is not the case.

To a remarkable degree, ABC tutors mirror the larger student body - 75% are public school graduates, 60% belong to fraternities, 15% are varsity athletes (including this year's football captain, Randy Wallick). Where the tutor profile does differ from the campus profile is in the three areas of race, affluence, and academic achievement. Thirty-five percent of the tutors are Negro as compared with less than 3% of the student body. This reflects a definite effort to provide black support for the 70% of the ABC students who are black. Sixty percent of the tutors have received financial aid as compared with 40% of the student body. The largest difference, however, between ABC tutors and other undergraduates is in the area of academic achievement. The academic records of the 30 tutors who are now alumni show that 21 of the 30 graduated with honors. This number includes seven members of Phi Beta Kappa and four Rhodes Scholars.

At its best, the experience of living in the ABC residence and teaching in the high school forces the undergraduate to grapple with the tough questions of human growth and development. Why does one student work slowly and one fast, one smoothly and one awkwardly, one under pressure and one when left alone? What accounts for one visualizing spacial relationships and his neighbor "seeing" everything in one dimension? Why does one come eager and one bored, one cooperative and one hostile, one thoughtful and one selfish, one modest and one arrogant? Who should teach? What should be taught? How? What is the proper role of administrators, school board members, and parents?

And the resident-tutor may come to understand ways in which one motivates the unmotivated, the advantages of indirect as opposed to direct education, the hazards of threats and sarcasm, the proper uses of punishment and reward, the power of example. And he may have to make up his mind about those middle-class values much maligned by his generation planningahead, keeping appointments, following schedules, making good on commitments, being accountable for one's actions, subordinating one's self to others, self-discipline, humility.

The future of ABC, in a very real sense, is in the hands of college under-graduates. Much of its direction is their responsibility - the selection of tutors, preparation for the summer program, visits to secondary schools, recruitment in ghettos, generating interest in new communities, staffing the ABC residences, visiting ABC homes and families, circulating newsletters, and directing the summer program. For each boy and his family, they work to sustain those hopes and aspirations that were quickened when ABC entered their lives. Under-graduate response has been widespread, enthusiastic, and in dramatic contrast to those who stand apart from all such efforts contemptuous of "a sell-out, the white man's bag, establishment charity, 19th century noblesse oblige, paternalism, and middle-class morality." Unstint- ing of themselves, unflagging in their optimism, soberly aware of their responsibilities, these undergraduates, more than any of us, have persuaded ABC students that they can hold their own with the best that this country can produce.

Every human enterprise needs what our Asian friends call "the one" - the Director. Two years ago, when the public school ABC idea took shape in the minds of a few people in Hanover and Norwich the group turned to "the one" whose skill in the classroom, experience in housemastering, and personal blend of compassion and toughness made him an ideal candidate - Tom Mikula, a member of the Phillips (Andover) Academy mathematics faculty who had served ABC for three summers as Mathematics Coordinator. The group wanted someone who knew, as only a private school housemaster can know, what it means to commit oneself and one's family 'round the clock to the education of other people's children. The person must be clear in purpose and resolute in his determination to share, daily, all the frustrations, agonies, and triumphs of young people beginning their mysterious journey to the far side of adolescence.

A person of this dedication is exceedingly rare: his home (and phone) becomes public, his wife the substitute mother, his children catalysts for "the action," his hair grayer. Through it all, he gives of himself fully, genuinely, patiently, not only to ten ABC students, but to the resident college undergraduates and, where spirit and energy permit, to his own family. His return is the satisfaction that comes from having participated in something worthwhile in a very special and very personal way.

Two families, the Tom Mikulas in Hanover and the Bill Deacons in Andover, are veterans. This September, seven other experienced teachers, with their families, became resident-directors.

ABC began with the avowed intention of selecting all students, Negro and white, from New England. Because we encountered considerable reticence among qualified applicants in the North Country and because of the special urgency of helping the Negro, the major portion of early ABC students came from urban areas and the South. The problem of recruiting youngsters from our own region was compounded by the difficulty of finding scholarship money for Vermont and New Hampshire applicants. In the early years, as we circulated their folders to private schools, these candidates simply did not generate interest comparable to that of the Negro, the Indian, or the Appalachian white. More recently, however, with the development of the ABC residence, we have found new opportunity to help promising youngsters from this region.

As we followed the progress of ABC students in Hanover High School we found ourselves wondering whether special tutoring, a close relationship with college undergraduates, pride in belonging to a special program, and the advantages of structured study and discipline would not similarly benefit high school students from Hanover and Norwich. Was it not possible that many of them had needs which were not now being met within the system? Was it not possible to offer them A Better Chance as we worked also with those who had been selected from areas of the country with more obvious social and educational problems? With guidance from school officials and beginning with six students whom they selected, ABC was extended to include six students from Hanover and Norwich. Along with the national ABC students and Dartmouth undergraduates, these local students spent each school night studying in the residence from seven to ten.

The experiment worked only moderately well. For a few it was important. For others, it became a burden and their participation was erratic. We believed the idea sound but concluded that local students must be given the opportunity to participate fully from the outset, including the ABC summer experience at Dartmouth. It was at this point that we turned to our neighbors in Lebanon to explore with them the possibility of starting an ABC program which would include both youngsters selected nationally and an equal number chosen locally from Lebanon families.

There is a Dartmouth tradition of sorts which points incoming freshmen to a class project. Traditionally, it may be a cannon hauled down from Hanover Center or a Saturday afternoon half-time display of questionable taste. September 1967 was different. Virtually before they were hatched from the orientation, many '71s were asking tough' questions about traditions of this kind and. whether they were, in fact, appropriate to the maturity of the Class or the climate of the times.

Though there is nothing inherently wrong with half-time antics at Harvard or dragging a cannon to the Green, the Class of 1971 believed that it could do much better. Happily, there occurred one of those rare occasions when good thinking is followed by equally good action. The Class Council met and referred to a class referendum the proposition that the Class of '71, while spending four years in Hanover preparing for selected graduate schools, would simultaneously commit itself to college preparation of promising young people who otherwise might not have the opportunity for higher education. 571 voted yes, 92 no. Of those voting yes over 50% indicated their desire to participate directly.

In collaboration with the newly formed Lebanon ABC Board of Directors, the Class of '71 assumed responsibility for staffing the residence and coordinating teams of additional tutors who commute to the residence each school night. From 7 to 10 they study with the twenty Lebanon ABC students - ten from Lebanon and ten from cities and towns beyond New England (all of whom attended the Dartmouth summer program).

Will this indeed grow as a class project or will it wither in the hands of a few stalwart but undermanned committees? Will examinations, papers, athletic contests, and road trips to Smith relegate these youngsters, five miles from Hanover, to an ever lower priority? Or will these college students sustain, responsibly, their full commitment to help these high school students through to college? In the answer to this question lies the final chapter of the Class of '71 Lebanon ABC Project. And the way in which that chapter is written may tell us something about the realities and potential of "student power" as applied to a major social issue of our time.

There was one member of the Class of '71 who had his own idea about how the class vote might be translated into concrete action. Duane Bird Bear, a Mandan Indian from South Dakota, submitted a proposal to Dean Seymour in which he pointed to the small numbers and high attrition of Indian students and recognized that "If the College wants to fulfill its commitment of giving Indian students a complete education and subsequently reduce the attrition rate, then it must do more than trust to its admissions procedures and hope the qualified students will earn a degree. Part of the problem stems from the fact that the College does not recognize that Indian students come from a background and culture that is entirely different from the typical American middle-class background as represented by the majority of students at Dartmouth. There should be an effort made to assimilate these students into this new environment, just as there is an effort made to help foreign students at Dartmouth."

Duane's initiative came at a time when those of us who had carried ABC responsibilities were increasingly pessimistic about our lack of success with the American Indian From the time in 1964 when the first ABC Indian got halfway to Hanover from the Cherokee Reservation and turned back, our record has continued erratic. Whereas our success with the Negro has been close to 90%, our success with the Indian has been no more than 60%. (When we reported the 60% figure to the Bureau of Indian Affairs they were eager to visit ABC to see what we were doing right!) Out of Duane Bird Bear's initiative, our continued inadequacy, and the Bureau's interest grew the Hartford (White River Junction), Vermont ABC Program for American Indians.

Ten students selected by the Bureau, five Chemawas from Alaska and five from various tribes scattered throughout the Southwest, along with ten Hartford youngsters selected by the Hartford ABC Board of Directors, attended the Dartmouth ABC summer program. (Though wishing we might somehow change the number to nine or eleven, we stayed with ten, as it developed, not-so-little Indians.) During the summer at Dartmouth these 20 students prepared for their accelerated program at Hartford High School. As in Lebanon, the ten Hartford students live at home but study in the residence each night with the other ABC students and a team of Dartmouth undergraduates.

We like to think that by creating a situation in which Indians are in the majority they may begin to develop some of the determination and confidence characteristic of other ABC minority groups. Though the experience of the past five years prevents us from being overly optimistic, we are hopeful. If the project does succeed, and certainly the citizens of Hartford have done an extraordinary job in launching this effort, it may be that Dartmouth will for the first time in two hundred years begin to take seriously Eleazar Wheelock's historic commitment to the people whose land we occupy.

Over the past year we have met with school administrators and school board members in other Upper Valley communities to determine potential interest in ABC. We are encouraged to believe that should the Lebanon and Hartford programs prosper, others will follow. If this occurs, it will provide fuller opportunity for Dartmouth to serve communities and schools in its regional neighborhood. Undergraduates living in ABC residences and teaching in nearby high schools will link Dartmouth in its Third Century with that historic past when each winter the College closed so that its students could teach in schoolhouses throughout Vermont and New Hampshire.

We can envision Dartmouth eventually working closely with as many as ten Upper Valley communities which have committed themselves to ABC. And we would hope to see this pattern duplicated elsewhere. For this reason, five of the new public school programs begun this September were located near a college or university. In addition to the Lebanon and Hartford relationship with Dartmouth, the Amherst program uses Amherst and University of Massachusetts students, the Appleton program draws upon Lawrence University, and the Northfield program is staffed by students from Carleton College. These programs each follow the basic pattern established in Hanover and more recently in Andover.

During the initial years of operation, the cost of educating ten disadvantaged youngsters in a public school residence is approximately $30,000 per year or $3,000 per student.

Depending upon the extent of its own resources, a community developing ABC receives two or three years of outside financial help. In order to qualify for these funds, the community must first raise one-third of the annual cost or $l0,000 each year. This one-third can be met through a combination of cash and in-kind contribution.

Communities have been imaginative about meeting this requirement. It is accomplished most often through a combination of tuition waiver, medical contributions, reduced rent, tax benefits on the residence as an educational facility, the obtaining of serviceable second-hand furniture, and free labor by skilled (and not-so-skilled) workers for remodeling, plumbing, and repairs. Two additional requirements must be met before the community qualifies for the remaining two-thirds from outside sources - approval of the residence and the resident-director by the national ABC Director on the Tucker Foundation staff.

The money for the summer ABC and the two-thirds assistance to newly developing public school communities comes primarily from private sources - corporations, foundations, and individuals. Roughly 10% of the 100 public school students are supported by the Office of Economic Opportunity.

It has been our experience that the per-student cost can be lowered in each successive year of operation. It is doubtful, however, that in many communities it can be lowered to the point where outside funds are no longer necessary. It is our hope, nonetheless, that eventually small scholarships financed jointly by federal, state, local and private sources might provide a full year of education in an ABC residence for as little as $l,000 per student.

This seems especially realistic for a community that is able to obtain both a tuition waiver (as five have already done) and the funds to purchase the residence outright. With these two major items provided for, financial assistance is necessary only for food, transportation, upkeep of the residence, a cook-cleaner, personal expenses, and insurance. Through a program of self-help the students, collectively, earn their $3 weekly allowance and a portion of their travel expenses for the spring vacation trip home.

In addition to these expenses, there is the initial cost of preparing the students in the summer program. As part of their vote which established ABC in 1964, the Dartmouth Trustees provided free dormitory housing. The other summer costs which amount to approximately $l,000 per student must be raised annually by the Tucker Foundation from outside sources.

We believe that the ABC student who has the capacity and courage to make his way in the high school of a predominantly white community will take with him confidence and self-esteem that will enable him subsequently to compete in selective colleges and universities. We believe also that the ABC experience will enable him subsequently to provide the leadership so desperately needed by his people.

The public school community that accepts the ABC challenge not only provides the opportunity for such accomplishment but also gives something special to the education of its own children. In the words of a citizen of Andover, Mass., "ABC is an opportunity for our community to demonstrate whether or not it is prepared to move confidently into the future - a future which must include people of all races and backgrounds if our town is going to provide our children with an environment that is relevant to the world in which they are going to live."

This nation has vast material resources and equally vast human needs. By mobilizing local initiative, ABC provides one way in which these resources can serve these needs - now.

The primary question for the future is whether hundreds, perhaps thousands, of communities throughout the country will stake their resources and energy on the proposition that our American society must offer equal educational opportunity to every youngster — in short, that the American dream will become a reality - that America is believable.

In April, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, the Trustees established a committee to "review Dartmouth's commitment to the objective of equal opportunities with a view both to strengthening existing programs and to developing in all sectors of the institution appropriate new initiatives." Under the chairmanship of John R. McLane Jr. '38 of Manchester, N. H., the committee subsequently recommended that the Dartmouth alumni might play an important role in the national expansion of the ABC public school idea. At its June meeting, following a presentation by Chairman McLane, the Alumni Council voted to establish a committee to work with the Tucker Foundation in extending ABC to public schools across the country and to consider participation in other activities which may be recommended by the McLane Committee and approved by the Council.

Such a committee, if purposeful and energetic, could prove an important example to undergraduates frustrated by what they perceive as irrelevance and rigidity within existing organizations. And such a committee may enable alumni and undergraduates, spanning the generations, to work together to help solve a truly Great Issue of our time.

ABC boys attending Hanover High have breakfast at their Wheelock St. residence.

John Brigand '69, resident tutor in Hanover,with Beverly Love, who enteredDartmouth from Hanover High this fall.

Like the other ABC students at HanoverHigh School, Winston Baker (c) enjoysa busy and friendly school experience.

Bill McCurine '69 (l), associate directorof the ABC summer program, withDuane Bird Bear '71, who sparked theclass project for Indians at Hartford, Vt.

Thomas M. Mikula, Director of ProjectABC, is also resident director of theHanover home where the ABC boys live.

Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall meeting in Washington with American Indianboys on their way to Dartmouth for the fifth summer session of Project ABC.

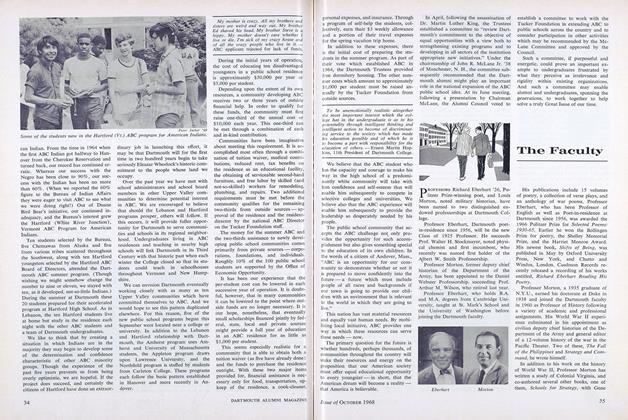

Some of the students now in the Hartford (Vt.) ABC program for American Indians.

Our need is to build more just communitieswhere equal opportunity for all,regardless of race or color, is the realitythat morally as well as economically canalone validate our faith in a competitivesociety. It is, I think, not mere rhetoric tosay that the future of my country dependson the outcome of this educational undertakingas it has never previously dependedon any undertaking in war or peace, exceptpossibly our Civil War. - President John Sloan Dickey, Convocation Address at Toronto University, 1968.

At the heart of the matter is this question:do communities like Andover, isolatedas they are from a problem. that affects themainstream of America, have a responsibilityto concern themselves directly withhelping the lesser privileged peoples of thiscountry to help themselves?—The Andover (Mass.) Townsman, February 2, 1967.

He was the best friend I ever had andthe best friend anyone could ever have. Hetrusted me a great deal and I thank himfor that. ... It gave me more confidence. -ABC student writing about his Dartmouth tutor.

The chief changes since I last spoke withyou have been internal. The decisive factorwas the opportunity of working in ProjectABC last summer. It was the first time thatI have ever really invested myself in someone else, and the experience was richly rewarding.In particular, I found that thesettlement that I had thought that I hadmade with life during my last years atDartmouth seemed thin, brittle and unreal.Views that I had thought arose from aclear observation of practical affairsseemed cynical and lacking in a core ofhuman concern for myself or others. Dartmouth Resident-Tutor.

After going to school in _________ foralmost three months I can see the differencein schools. Now I wish I had not given upthe chance I was given in the ABC program.I really wish I could do it over againand believe me I would really put all myability into the project. But, I gave up mychance and I would like to tell you Mr.Mikula that I admire you for all you aredoing for this project. You have given upmuch of your privacy to help the boys andgirls of the city and to me you are a goodexample of someone who cares for mypeople. ___ ABC dropout to ABC Director.

It's time Lebanon residents give theirchildren a chance to meet people with adifferent color of skin and from a differentbackground, for indeed, it seems to us thatLebanon school children will benefit asmuch, if not more, from an ABC programthan the ABC boys themselves. — Valley News editorial, April 10, 1968.

"... the most inspiring single event ofthe year." - Dean Thaddeus Seymour, commenting on the Class of '71 Lebanon ABC Project.

______ _______ is one of those rareand interesting students who show up fromtime to time on the edge of this reservation-bound,small Wyoming town. Hisabilities are high - his learning accomplishmentstoo quick and below his aptitudelevel. Why? He comes from an areakindly and realistically defined as one ofcultural lag.... He is ready for a librarythat has Dickens, Hardy and Conradrather than the horse and pony novels wehave. He is ready to hear a different drummer - and let the tune be Beethoven orBartok - as long as it is not cowboy music.In short, he needs teachers, resources,and inspiration to challenge him. I shouldhate to think of him ending up with adusty open-mouthed mute stare so commonto this landscape. His ability is equal to it.His enthusiasm could meet such a challenge.His future could be far from bleak.Simply, he needs a break. - English Teacher.

My mother is crazy. All my brothers andsisters are weird and way out. My brotherEd shaved his head. My brother Steve is ahippy. My mother doesn't care whether Ilive or die. I'm sick of my crazy house andof all the crazy people who live in it. - ABC applicant rejected for lack of funds.

To be unemotionally realistic altogetherthe most important interest which the college has in the undergraduate is as to hispotentiality through intelligent thinking andintelligent action to become of discriminating service to the society which has madehis education possible and of which he isto become a part with responsibility for theeducation of others. - Ernest Martin Hopkins, 11th President of Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJOHN THORNTON OF CLAPHAM

October 1968 By FRANK W. FETTER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

October 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1968 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

October 1968 By DR. STANLEY B. WELD, FLETCHER CLARK JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1968 By JOHN HURD, INGHAM C. BAKER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

October 1968 By THOMAS J. SWARTZ JR., HERMAN E. MULLER JR.

CHARLES F. DEY '52

Features

-

Feature

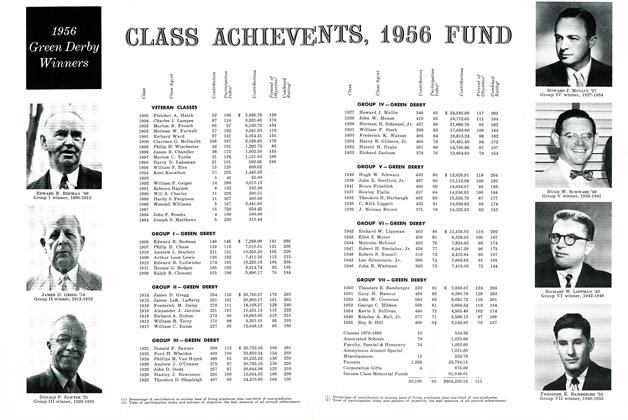

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVENTS, 1956 FUND

December 1956 -

Feature

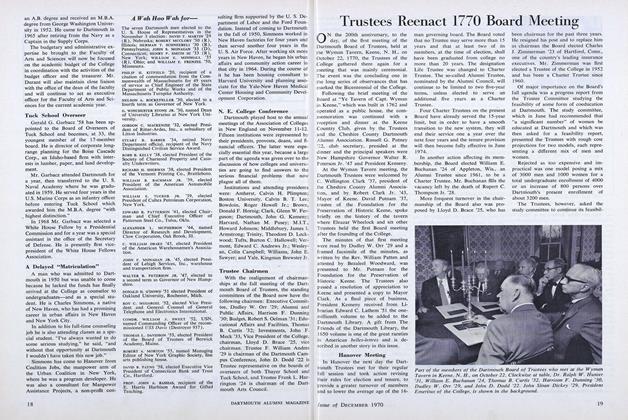

FeatureTrustees Reenact 1770 Board Meeting

DECEMBER 1970 -

Feature

FeatureExtracurriculn Vitae

January 1975 -

Cover Story

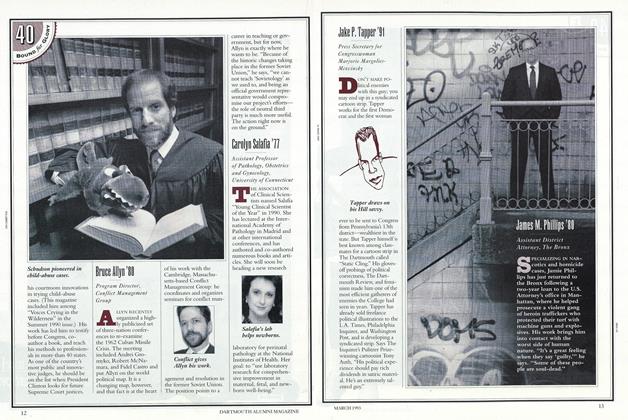

Cover StoryJames M. Phillips '80

March 1993 -

Feature

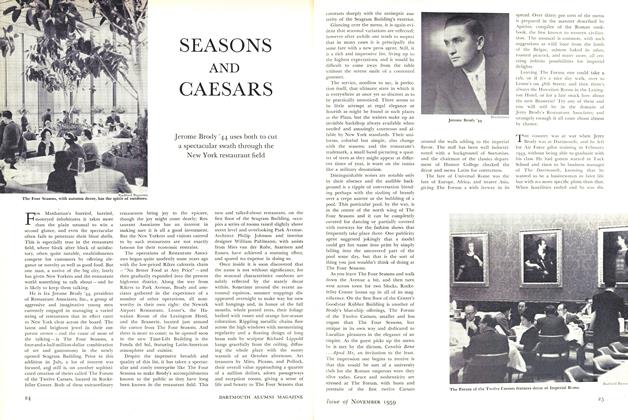

FeatureSEASONS AND CAESARS

November 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PUT A SMILE ON AN ADMISSIONS OFFICER'S FACE

Jan/Feb 2009 By MARIA LASKARIS '84