Dear Mr. Cunningham; Please forgive this belated reply to your challenging letter of May 11 on the Dartmouth “strike.” I have delayed in order to find time for a rather exhaustive exposition of thoughts that have been on my mind for some time, and I certainly must also apologize for the lengthiness. I was in Vietnam for a total of more than five years between 1953 and 1968, so the subject comes close to the bone. At the same time, I am a lifelong member of the Dartmouth family (my father was a professor there for a quarter century), and your strike has stirred my keen interest.

Let me say at once that I join other alumni with whom I have discussed the strike in approving the moderate manner in which you have expressed your views. I also concur with your thesis that the United States should get out of Vietnam, but for quite a different set of reasons.

First, about the argument of your letter. You have raised some critical questions, but more as unsupported assertions than a reasoned plea. What is your authority for writing that it is a strike “by Dartmouth College?” Were all the students and faculty members polled? One of the reasons for the present disarray of the nation certainly lies in bewilderment resulting from that kind of claim, the question of who speaks for whom. The public opinion polls continue to show a majority supporting Mr. Nixon’s policy in Indo-China (together with a wish to get out when possible), so what is your authority for writing that “Mr. Nixon’s ‘Silent Major- ity’ is not a majority?”

Similarly, how about some arguments to support your point that “expanding the war is a dangerous way to achieve peace?” If that is true as a general principle, as you imply, does if follow that the Allies were wrong to land troops in Europe in 1944 to destroy the Nazis, or indeed that Washing- ton was wrong to expand the war by crossing the Delaware? If you are a pacifist, opposed to all war, then let’s hear the arguments. It just isn’t good enough to be unqualifiedly in favor of peace. I’m sure you realize that, but you have nevertheless provoked me to try to analyze the question as it applies to the mess we are in today, and particularly to the dilemma of Vietnam.

If there is a single, dominating fallacy in the thinking of a good many people today on foreign policy, it is the idea that you can “declare” peace, that we have the option simply to disarm and spend the money on programs like cleaning up the environment. (In fact, mankind surely has the resources to preserve both the environment and the peace.) It is a harsh but undeniable fact that human beings are the only animal with an instinctive drive to fight their own species. However repugnant the thought may be, the only peace the world has ever known has always been created by force, and weakness has always invited aggression. To deny that reality is to be contemptuous of thousands of years of human history, yet there seems to be a countervailing instinct among modern democracies to try to deny it anyway.

We fought in World War I to “make the world safe for democracy,” but the principle had been put aside twenty years later when a new generation permitted the rise of Hitler. Perhaps it is a characteristic of youth raised in a democratic environment to insist that war is unthinkable. I can recall petitions circulated at Dartmouth in the 1930’5, when Hitler was already in business, in which we were invited to pledge never to bear arms, no matter what the issue. That kind of thinking—personified by the youthful hero of the era, Charles Lindbergh—led us to defer confronting the Nazis until it was almost too late. By 1945, when the war was won, it had become an absolute that aggression anywhere was a peril that must be opposed, and it seemed inconceivable that this could ever again be denied.

Events led the Allies to invoke the principle almost immediately in the late 1940’s as the Russians converted Central Europe into a system of colonial provinces, while China fell to the Communists in one of the greatest disasters of our time. The global American reaction against further aggression, reinforced by the formation of NATO, was so successful that it forced the Communist powers to turn inward to improve their own standards of living by better management, and eventually to grudg- ing relaxation of a few of the rigid Stalinist constrictions on individual freedom. The frustration also led to internal fragmentation of the Communist world, the Soviet-Chinese schism, and such liberalization movements as Poland and Czechoslovakia. But it is essential to remember the lasting wisdom in President Kennedy’s remark that the nub of the argument among the Communists is “how to bury us.”

It is a grim—yet familiar—irony that members of your generation, as the benefi- ciary of a quarter century of peace preserved by American power, as well as years of unprecedented economic prosperity, should now be opposed to some of the key policies that made this possible.

The irony becomes even more uncomfort- able when you consider the change in the situation today as compared with the immediate postwar years when the U. S. inherited global responsibility as the dom- inating power in a shattered world, capped of course by our atomic monopoly. As recently as 1958, I stood on the beach at Beirut and watched the U. S. Marines come ashore without opposition. Today the Soviet Navy maintains some seventy-odd warships in the eastern Mediterranean, which certain- ly is no longer an American lake. There have been similar shifts in the power balance in many other places, as nations recover the muscle lost in World War 11. Despite the views of many American rightwingers, we no longer have the option to apply military force by whim all over the world.

On the contrary, we are slowly reverting to the prewar status when security could be achieved only collectively through alliances among strong and sovereign nations. In direct proportion to our loss of unilateral power, the need for a clear and steady understanding of our values and objectives has grown, along with the threat to our ultimate security in a troubled, confused and often hostile world. We are moving into a period of crisis in international security comparable to the angry, directionless furor of the late 1930’5. By chance of history, Vietnam has become a critical focus of today’s furor.

The essential U. S. objective in Vietnam was the same as in World War 11, the Berlin Blockade, and Korea: to block totalitarian aggression, as represented this time in the effort of the Viet Cong to take over South Vietnam by force. We came close to success in our support for Ngo Dinh Diem, who remained in power for eight years until 1963. However badly the Kennedy-!ohnson- Nixon decisions of the 1960’s may look today, there never was a clear-cut moment when it was logical to get out of Vietnam. Until now. And even now a substantial part of the argument relates to the unacceptable damage that Vietnam is doing to the American body politic, rather than the case for being there in the first place.

The explanation of the bind we are in lies in a reality of the struggle in Vietnam that has received deplorably little attention: that the error was not in the principle of U. S. intervention, but in a puzzling failure of performance after we got there. The failure was so monumental as- to stagger even the critic—the inability of the world’s most powerful nation to establish order among 15 million peasants despite the commitment of a half-million highly trained troops, sup- ported by an annual budget of $3O billion, the best weaponry the world has ever known in unlimited quantities, reinforced by more than a million men in the South Vietnamese forces.

Vietnam has been the first outright failure of a great national undertaking in modern American history, and the psychological shock certainly lies at the root of the fragmentation of our country today. In effect, millions of Americans, especially young Americans, have tried to sublimate the failure in Vietnam, or excuse it, by saying that we should not have been in Vietnam in the first place. With more justification, they have read the Vietnam disaster as evidence that something is wrong with American leadership, and in the thinking of the generation that got us into this mess, i.e. my generation.

The desirable reaction now is not hind- sight recrimination against the Establish- ment, but to try to understand what really happened in Vietnam, and to think in terms of better performance next time. You can be sure there will be a next time, no doubt with your generation in the saddle, and with problems that may not even be conceivable today.

Ideologically, Ho Chi Minh’s Vietminh movement, which he began organizing in the 1930’5, was an extension of Chinese Communism. But it was also inspired by Vietnamese hatred of French colonialism, which surely ranks among the least enlight- ened of our time. The Vietminh contained a distinct “Titoist” character in the sense that they sought successfully to steer a relatively independent course between the Chinese and the Russians. But the Vietminh were always dedicated to the prime objective of extending Communist power into the rich lands of Southeast Asia and the subjugation of the peoples who lived there—as proved most recently by revelations of the extent of Vietnamese Communist penetration of Laos and Cambodia.

The Viet Cong in South Vietnam were formed out of Vietminh stay-behind cadres after the Geneva agreements of 1954 that partitioned the country. They have always been such total creatures of the Vietminh regime in Hanoi that very few Westerners today can even name any of the V. C. leaders. U. S. intelligence has mountains of evidence, such as secret radio intercepts, proving that the V. C. take even minor operational orders directly from Hanoi or its covert southern proconsul. The Communist propaganda line that the V. C. are indigenous patriots is as absurd as it is successful among unknowledgeable Western- ers seeking an excuse for failure in Vietnam.

Certainly the various regimes in Saigon have been corrupt, weak and a major cause of our plight today, but none of them compares with the totalitarian ruthlessness of the Vietminh/Viet Cong. In degree of cynically efficient subjugation of the human mind, the Asian variety of Communism makes even the Stalinists in Russia and Hitler’s Gestapo seem like gangs of Mafia thugs. (If you have the time one day, read Ed Hunter’s book Brain Washing in RedChina.)

In 1954, I witnessed the Vietminh taking over Hanoi from the French, and it was a spectacle I can neither forget nor adequately describe. You could literally feel the might of a superbly organized police state come over the people, insidiously clothed in patriotic slogans, imposed by lock-stepping troops in tennis shoes. “You are deliriously happy,” shouted the agit-prop workers through megaphones, “your joy is un- bounded.” It was “joy” by the numbers, imposed, disciplined joy from which any true spontaneity (which surely existed) was drained in advance, never again to be tolerated.

North Vietnam became a community where it is a crime not to report to the police a simple suspicion of a neighbor’s political loyalties, meaning the slightest digression from enthusiastic support of the official line. A man was subject to arrest if he merely lived on the same street as a discovered offender and had failed to detect and report him: he was guilty of a crime he did not know he had committed. The degree to which the Asian Communists have suppressed human dignity and the most basic principles of human freedom is difficult for an American even to conceive.

How, then, did the U. S. go wrong in Vietnam? Essentially the error resulted from a frozen misconception among American leaders that the tactics we used successfully in World War II and Korea must be equally applicable in Vietnam. Uncannily, this was exactly the mistake the French made in Indo-China, yet we failed to learn from them. We assumed, as the French had, that we could overwhelm the Viet Cong with tanks, airplanes and big guns. We refused to recognize—and this is the key to the disaster—that Mao Tse-tung and Vo Nguyen Giap had developed a new form of warfare. (The Communists call it “liberation war,” a huge misnomer in view of its objective, but the term has stuck.) It was designed specifically to make it possible for an army of peasants with little capital or technological resources to defeat an ultra- modern enemy. In effect, the technique was to outflank a modern force by astonishingly imaginative guerrilla tactics against which fancy weaponry was almost meaningless.

If you are interested in this, there is an excellent book on the subject called No ExitFrom Vietnam by Sir Robert Thompson, published about a year ago. Thompson was one of the architects of the British victory over the Communist insurgents in Malaya in the 1950’s and subsequently served in Vietnam for about five years as head of a British Advisory Mission. His advice to the Americans and Vietnamese was treated with deplorably little response.

The key to the Asian Communists’ success, as Thompson’s book spells out, lies in their techniques for blending themselves with the people so totally, and covertly, that the Western enemy is denied a target for his big guns and airplanes—except the target of the people themselves, which of course is unacceptable. The blending process is based in large measure on intimidation—“support us or take the consequences”—followed up by intensive, compulsory indoctrination of the people in Communist ideology, rein- forced by police state controls.

The heart of such controls rests in tens of thousands of covert agents—the so-called “infrastructure”—who have been working in the hamlets in many cases for decades, creating communities where the real boss, like the Mafia in Chicago or New York, is the undercover commander who enforces his wishes by sweet persuasion if possible, uninhibited terror if necessary. For years, there has been an average of better than fivethousand murders and kidnappings annually throughout South Vietnam, mostly of hamlet leaders, teachers and other local government employees. (Indeed the fact that the Saigon government can still recruit such officials, despite the terror, is remarkable evidence of the degree of anti-Communist feeling that continues to exist 'in the South.)

Seeded through thousands of the 12,000 hamlets in South Vietnam, the infrastructure not only provides recruits but, equally importantly, it also is one of the world’s best intelligence networks. It makes it virtually impossible for Allied units to achieve surprise in attacks on the Viet Cong, or even to find them at all. It prevents establishment of a lasting Saigon government presence, except through permanent occupation, and of course its observation network is the reason who so many thousands of Allied “sweeps” into enemy territory have found nothing but empty jungle. V. C. terrorization of the peasants has been revealed repeatedly by their failure to warn U. S. and Vietnamese forces of impending ambush, or hidden mines, leading occasionally to such uncontrollable anger as the My Lai mas- sacre.

Generally, Allied tactics in Vietnam have been based on exactly the reverse of the correct priorities. Where the Communists concentrated on control of the people, we tried first to achieve “military” victory by seeking to bring the V. C. into classical big- unit battle. The Communists shrewdly exploited this to keep us engaged in the bush along the frontiers, and thus off the backs of the secret agents who had fastened police state discipline on the hamlets. During the past year or two, there has been grudging recognition of this mistake, leading to an ambitious “pacification” program in the countryside which has improved the situation appreciably. But the program never was given first priority; its application has been sloppy and unimaginative; and the V. C. infrastructure in many parts of the South is as strong today as ever.

By dint of sheer numbers and firepower, of course, the Allies did force the Com- munists to bring in hundreds of thousands of North Vietnamese troops to stay in business. By 1969, the struggle was slowly swinging our way, and we probably could have prevailed eventually, but we will never know. The cost was too high to preserve the necessary political support at home. We were, in short, suckered into defeat by attrition exactly as Mao and Giap had planned. And our disastrous effort to try the same sterile tactics in Cambodia has now demonstrated that the Nixon Administration still does not understand what went wrong.

It has become fashionable among critics of the Vietnam war to say that we failed because the people did not want our side to win. This is certainly not the case. The South Vietnamese know all about the harsh life in the North, and there is strong evidence that they prefer the Saigon government for all its faults. If that were not the case, the government would have collapsed years ago. The V. C. plainly expected just that at the time of the so- called Tet offensive in early 1968. Instead, not a single South Vietnamese unit defected, and the offensive ultimately was judged to be a major V. C. blunder. The ingredients unquestionably existed for victory over the Viet Cong and the establishment of a stable, independent government, if only we had been smart enough to recognize the right way to go at it.

If the U. S. had devoted its main effort to rooting out the infrastructure, the mecha- nism of V. C. control of the people, and to providing direct and permanent security to the hamlets, we probably could have saved South Vietnam. It probably could have been saved, moreover, with appreciably less cost in lives and treasure. In effect, what was needed was a massive police action to establish real security at the hamlet level, as the British demonstrated in Malaya, not the empty big-bang tactics of maneuvering armies.

Why we refused to see this—even though men like Thompson and a good many junior officers in the field began pushing for such tactics years ago—is baffling. Despite the fact that we were facing the first great failure in American military history, we

changed commanders in Saigon only once in five years—in dramatic contrast with our performance in other wars that were going badly, e.g. the half-dozen commanders that Lincoln went through before he arrived at Grant. A form of hardening of the arteries in the Pentagon and White House perhaps? Or the intractible stubbornness of Lyndon John- son and Generals Taylor, Westmoreland and Wheeler? Whatever the explanation, this has been a sorry moment, and the peril of failure to learn from it is incalculably great.

Thus my reasoning in writing at the outset that I agree we must get out of Vietnam. The cost of bumbling has simply become greater than the real estate is worth, not to speak of some 40,000 American lives in futile sacrifice, and the violent disruption of our domestic community.

If you have the fortitude to struggle through all this, I will be pleased to hear your reaction. In any case, it has been a useful exercise for me—and it has certainly taught you a lasting lesson about the dangers of writing provocative letters to alumni.

The letters sent by undergraduates to Dartmouth alumni during Strike Week in May produced a voluminous exchange of correspondence, but no other undergraduate received an an- swer quite like the one William 1. Cunningham ’72 got from lohn M. Mecklin ’39, a member of the Board of Editors of Fortune Magazine, who wrote at length about Vietnam and what went wrong there. Mr. Mecklin as foreign correspondent and as Public Affairs Officer in the American Embassy in Saigon spent more than five years in Vietnam between 1953 and 1968. He is the author of the book. Mission in Torment: An Inti-mate Account of the U. S. Role inVietnam (Doubleday, 1965). From 1953 to 1955 he was foreign corres- pondent for Time in Vietnam, cover- ing the disastrous French campaign and the establishment of the Diem regime. He later covered the Middle East and West Germany for Time. His father was the late John Moffatt Mecklin, renowned Dartmouth profes- sor of sociology from 1920 to 1941.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryLiberating the Ph.D.

October 1970 By Robert B. Graham ’40 -

Feature

FeatureEleazar Is Outdone

October 1970 By Charles Jay Kershner -

Feature

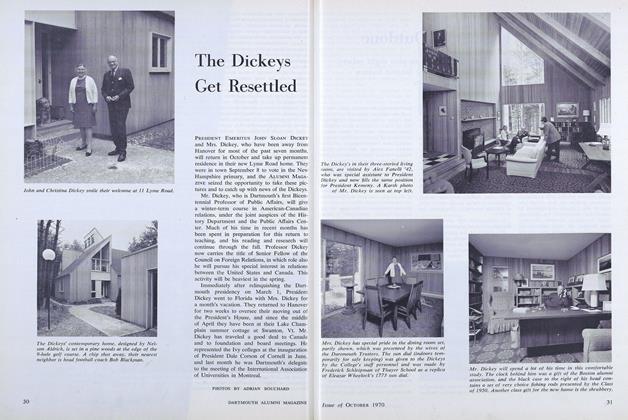

FeatureThe Dickeys Get Resettled

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

October 1970 By William R. Meyer -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

October 1970 By Jack DeGange -

Class Notes

Class Notes1955

October 1970 By JOSEPH D. MATHEWSON, JOHN G. DEMAS

Article

-

Article

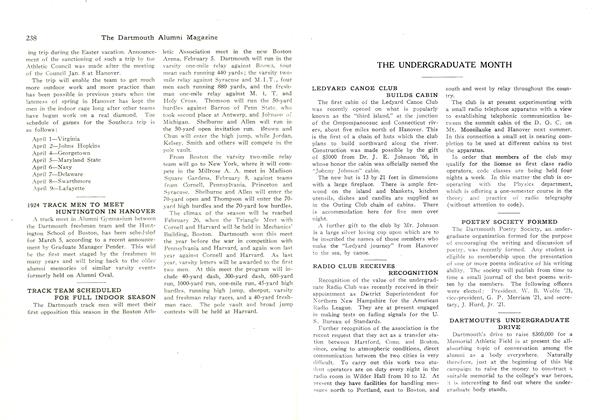

ArticleLEDYARD CANOE CLUB BUILDS CABIN

February 1921 -

Article

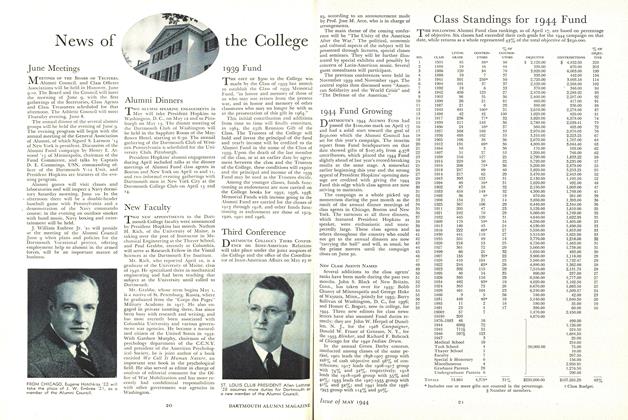

ArticleThird Conference

May 1944 -

Article

ArticleCaptain Leonard R. Kojm

MAY 1969 -

Article

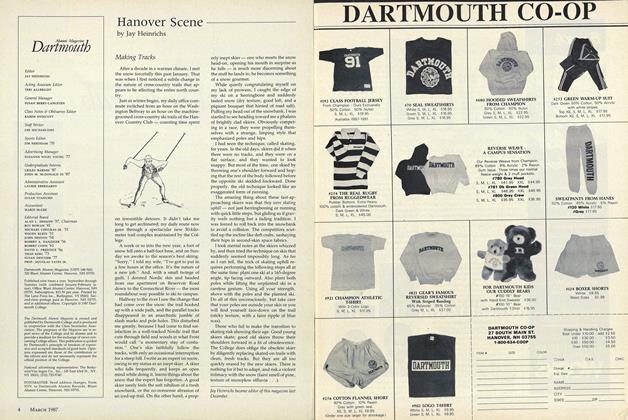

ArticleHanover Scene

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

Article3-D in 2-D

April 1995 By Robert H. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Off-Broadway

SEPTEMBER 1997 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75