Maurice Mandelbaum'29. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press1971. 553 pp. $15.

The field of 19th Century intellectual history has not lacked major interpretive and synthetic studies, but Mandelbaum's work is clearly in a class by itself. This book is the product of years of deep reflection and is likely to provide the stimulus for major reinterpretations and the germ for much future. scholarship. In the jargon of the guild, it is the kind of study which intimates "a book in every footnote." It is rich and provocative for both historians and philosophers (which, given present circumstances, is saying a great deal), but also for the dedicated layman who is interested in exploring the origins and implications of the premises of much of our modern thinking.

Mandelbaum's command of his sources and materials is staggering. He ranges freely but also very surely among the major European intellectual traditions and thinkers of the period, an exceedingly diverse and complex group of men including Hegel, Comte, Mill, Darwin, Marx, and Nietzsche. In addition he draws upon a host of less well-known figures such as the intuitionists F.H. Jacobi and Maine de Biran, the scientifically oriented philosophers Hermann Helmholtz and Ernst Mach, and an eclectic group of social psychologists and anthropologists. The author has a truly remarkable ability to align thinkers drawn from various disciplines and traditions along common intellectual fronts without divesting them of their individual peculiarities and nuances. In his approach Mandelbaum has avoided the pitfall of historical anachronism which plagues many works in the field.

The work is organized thematicaly, according to what the author considers to be the dominant assumptions or pattern ft presuppositions operative in the thought of the period. The major themes emerge as: (1) historicism, which is not merely a matter of the cultivation of "historical seinse" or a manner of looking at things historically, but rather the view that a phenomenon can be understood and evaluated only in terms of a schema or process of overall develoment; (2) the related but not identical doctrine of the malleability of man, which stressed the infinite mutability of human nature and which coalesced with historicism to foster an implicit belief in "Progress"; (3) the diverse currents of irrationalism which were united in the effort to impose strict limits on man's rational intellect and, in some cases, to discredit it altogether. Mandelbaun finds that the basic philosophical conflict of the century was waged between two polar positions of metaphysical physical idealism and positivism. He effectively tively refutes the notion that the 19th Century was an age of irreligion or philosophical materialism. Religion in fact assumed the subtle form of various doctrines of "divine immanance" and became linked with the growing concern with the deeperecesses of the mind and unconscious. By way of the author's lucid exposition we are led to recognize that the pattern woven from these strands is, with some important exceptions and alterations, still very much at the foundation of modern thought.

Each extended historical section of the work is concluded by a critical and theoretical treatment. Mandelbaum does not conceal his serious objections to the dominant philosophical and intellectual modes of the 19th Century; implicit in the work in his concern that we move beyond this questionable legacy. He argues trenchantly against the premises of historicism, the idea of the unlimited variability of human nature, and the misguided yearning for concrete immediacy and "identity with things" which lay at the heart of the intuitionist attack on conceptual reason. The author emerges as a philosophical pluralist and individualist and a firm defender of the claims of human reason.

The book, written very concisely, requires a corresponding effort of concentration on the part of the reader. It is not susceptible to a carefree overview, for Mandelbaum is almost surgically precise. But the work repays sustained attention in full. The distinctions between "organicism" and "geneticism," distinctions between the systematic and critical forms of positivism, between the explanatory and evaluative aspects of historicism, and between the rationalist and voluntarist forms of idealism are particularly apt and useful. The extensive footnotes at the back of the book are highly informative and integral to the work itself. They serve to clarify a great number of tangled textual problems—due in part to poor previous translations—and also to bring the treatment of issues up to the level of the most recent contemporary debate.

This is a "relevant" work of intellctual history and philosophy. One hopes that Mandelbaun will provide a sequel for the 20th Century.

Dartmouth Instructor in History, Mr. Ermarthconcentrates on France, Germany,Italy and Austria in his course entitledLiberalism, Democracy, and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Europe.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Plan

January 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

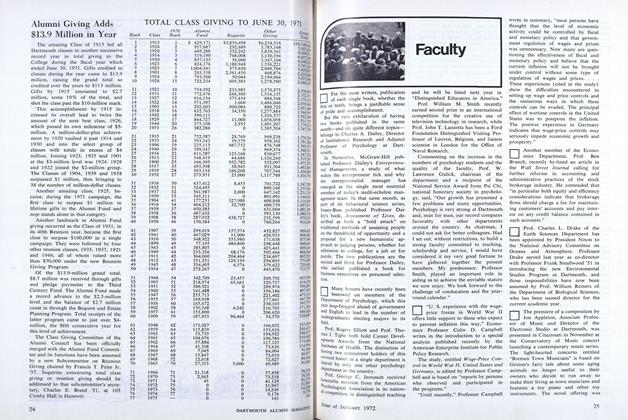

FeatureAlumni Giving Adds $13.9 Million in Year

January 1972 -

Feature

FeatureConserver of the Crafts

January 1972 -

Feature

FeatureAnti-Bigot

January 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureThe American Dream

January 1972 By A.T.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1972 By RICHARD M. ZUCKERMAN '72

Books

-

Books

BooksTROUT FISHING

June 1950 By Albert H. Hastorf -

Books

BooksThe Biology of Death

June, 1923 By H. G. Coar -

Books

BooksSUCH IS LIFE

June 1952 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksEDWARD COKE, ORACLE OF THE LAW.

FEBRUARY 1930 By James P. Richardson -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN BRITAIN, INCLUDING ENGLAND, WALES, SCOTLAND AND NORTHERN IRELAND, WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS.

OCTOBER 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE MAD DOCTOR'S DRIVE.

DECEMBER 1964 By R.J.B.