The December issue carried essayson "Why College?" by eight students,who for the most part expressed earnestand favorable feelings about college ingeneral and Dartmouth in particular.What follows is a sequel, obviously reflecting different, although no less earnest,points of view.

Although it is almost a year and a half later and I am now a senior, I still feel that some of the most significant aspects of my education took place while I was away from Dartmouth. There are others who share this view, but I can't pretend to adequately represent them. Instead, I will simply recognize those people, too many of whom are my good friends, by saying that some of the finest Dartmouth people I have known left the College before they graduated. Some of them never returned.

I've never made any claims of being a "Big Greener," but I think that there is a number of Dartmouth men and women, some who left and some who never returned, of whom it may be said that "Theirs was the Dartmouth Spirit."

I have to chuckle as I am now living in the Ledyard Canoe Club cabin during this, my last year at Dartmouth. You may recall that John Ledyard was a member of the sixth class at Dartmouth College, but left in the spring of the year 1773 when "he found the academic life too constricting to his liking." Ledyard then sailed the high seas with Captain Cook, joined John Paul Jones in establishing trading posts in the Pacific Northwest and later explored the Russian empire before he died in Cairo, Egypt, in 1789. It has been said that "His was the Dartmouth Spirit." I, unlike John Ledyard, returned to Dartmouth and would like to share some "before and after" thoughts about the Dartmouth Spirit.

In a speech before my high school graduating class, I quoted a few lines from a then popular song which perhaps best express that Spirit.

StandIn the end you'll still be youOne that's gone out and done thethings you set out to doStandAll the things you want are realYou have you to complete and thereis no deal.

As a sophomore at Dartmouth and after almost fourteen years of schooling, I felt that it was time to learn something a little bit different. Most of the men and women at Dartmouth are here because they know a lot of what schools think they should know. But for some, the urge to do (for John Ledyard it was travel and exploration, for me it was living and working in a different community) leads them to find something which may be equally important: what they don't know. I also felt the need to leave the Dartmouth environment which at that time was stifling aspects of my personal growth.

If it wasn't for the Tucker Foundation and their programs, I wouldn't be at Dartmouth today. I refer to the Tucker Foundation as people and it was working with people both in Hanover and in the Uptown neighborhood of Chicago that provided the challenges, successes, interests, and, most importantly, the failures that I needed and need - to experience. The academic may ask how it is that "experience" warrants scholastic credit. I would reply to that person that I have never put more into nor gotten more out of three term credits than I did in Chicago. To our critic I would add that we have a long way to go in developing methods and standards of evaluation for this kind of education. But develop them we must.

When I returned, Dartmouth had changed and I had changed, too. I have hearty praise for the decision to include women in the Dartmouth fellowship. I welcome the opportunity to grow as a man among both men and women. I've changed in that my academic motivation has been stimulated by my experiences. I have found new relevancy and have man) questions to ask, things to demand of myself and the world, and many things to learn.

The seas and the world became wider and deeper when John Ledyard left the College and began his explorations. Perhaps it may be said that the exploration of the world and self today has made it possible for some to find a similar breadth and depth around them and within them. Some return and others don't, but theirs is the Spirit as well - deep and clear.

BILL GEIGER '74

Is it worthwhile? Instructive? Firn?

I learned during the past two years at Dartmouth that a student will be able to use the college resources to their fullest extent only if he is self-reliant, resourceful, knows what he wants, and has the connections to make it. Someone not able to hound the Establishment with his goal in mind will have a rough, if not confusing, extravaganza ahead of him. I only regret that I did not have the fortitude or vision to see beyond the experiences I had.

When I was a freshman, I thought I had enough talent and desire to become a doctor, ideally a neurosurgeon. A fairly common attitude no doubt, but I had plenty of previous experience giving injections, I.V.s, assisting the surgeon, heading the minor wounds department, etc. in a field hospital for two years. A bit more exposure than average.

So my heart was set on being a doctor. If not, surely I would be inspired in the academic environs of Dartmouth.

My first encounter with this institution dedicated to teaching the undergraduate was with the Biology Department. I was treated like a number on a piece of paper, recorded, stacked and filed away for some future statitician. The professors' concern for the undergraduate was non-existent on a Personal level.

I labored less and less. I felt more fulfilled participating in extracurricular activities and by the end of the year - with don't care" attitude - I lost all of my precious study habits so painfully acquired in boarding school, lost my ambition become a doctor, and, for better or worse, my motivation to pursue academia. (But since most of the Dartmouth experience is supposed to be gained through one's social life, I can now pick up homely women, drink beer, smoke marijuana in quantity, sing rugby songs, and usually only pass out in my bed - or hers, as the ease may be.)

The summer of my freshman year I went to Europe, and soon forgot about my misgivings and was inspired by the different approach to life found in Europe. But this minimal input was soon extinguished when I returned to Dartmouth. I quickly slumped into my bad habits, got stoned, drunk, and laid all for the first time and decided that that was about all Dartmouth could do for me. Skiing for a while changed my mind, but the lousy weather and subsequent events in the spring forced me to a decision.

In the spring I became involved in a social event of significant proportions. I organized it, and had received verbal approval and go-aheads all along the way from the administration. The next thing I was aware of was the College emphatically denying any previous knowledge of the event and a manhunt to find yours truly. My faith in the College and the deans was shattered.

A week before the end of the spring term I decided it was time I should separate from the school and do some serious thinking ing about my future and how it relates to Dartmouth. If at all.

#J. M. W ILSON'7S

In the spring of my sophomore year (1972) I left Dartmouth for a period of 16 months. At that time I was a premen a prospective biology major and taking two lab science courses. Until then I had been doing moderately well academically, but realized it still wasn't good enough to get into medical school. More importantly, I began to have serious doubts about becoming a doctor. Subsequently. my academic motivations hit rock bottom.

I decided the most positive course of action would be to leave school and seek employment in a hospital. My reasoning was that this would afford a good opportunity to see the medical profession first hand and aid greatly in my decision of whether or not to continue as a pre-med. I would like to make it clear that leaving school in no way involved any dissatisfaction with the College, but rather was based on a dissatisfaction with my own performance. Also, at the time I left I had no doubts that I would return to Dartmouth.

I spent the next month and a half looking for a job in a Boston hospital. I was determined to spend the year on my own and be entirely self-supporting. With no hospital job in sight and my money running out, I took a job as a teller in a Boston bank. That summer I came to the conclusion that I had no desire to become a doctor. It was easy to see that I had been misleading myself for the past two years.

Work at the bank left me with a lot of free hours, and I began to seek ways to occupy my time. That summer there was a presidential campaign raging, and with an interest in politics I began doing volunteer work for Senator McGovern. I started off licking envelopes and doing zip codes at night after work at the bank. Eventually, I quit my job at the bank and took a fulltime position on the Massachusetts press staff for McGovern.

My job essentially was to serve as the Boston correspondent in a nationwide network organized to keep McGovern informed of what the media across the country were saying about his candidacy. This entailed picking up the newspapers as they hit the stands every morning at 1 a.m., writing up a report and sending it via telecopier to the Washington headquarters. The Washington staff would then edit the fifteen reports they received from around the country and send them on to McGovern to read first thing every morning. Naturally, working for McGovern in Massachusetts had its obvious rewards.

I extremely enjoyed my first taste of politics, and after the campaign I returned to the bank for another six-month tour of duty. In June of 1973, I again left the bank to take on a job as the assistant campaign manager for a Boston City Council candidate. I had met the campaign manager during the McGovern work, and he was anxious to have me experience the nittygritty of ward politics. At the end of August, I left the campaign to prepare to return to Dartmouth.

Looking back on my 16-month leave of absence, I have only positive feelings about the whole experiment. I would not recommend that everyone take time off in the middle of his college career, but the benefits for me were innumerable. I needed the time away to sever myself from my pre-med notions and to think about possible areas of study to take up when I returned. I consider my political experiences to be the most important asset of my year off, and the contacts I made will probably be very helpful in the future. I would like to add that at present I am a history major ... and glad to be back.

#JOHN PENBERTHY '74

Thesestudentssay yes

It seems that every year an increasingly large number of students decide to take some time off from their college careers to pursue non-academic interests, often returning to college after a year or two to complete their education. Reasons for doing this may differ from person to person, and I cannot speak for all such students, but perhaps I can help explain some of their reasons and feelings by telling about my own experience of "dropping out."

After two years of normal academic life at Dartmouth, I felt that something was missing from my education, something that would not be supplied by taking a wider range of courses or getting involved in a few extra-curricular activities. Most of my time in both high school and college I had spent studying, and after two terms of organic chemistry my dissatisfaction grew too strong to ignore.

I spent my sophomore spring off campus, as a resident tutor in the Concord, N.H., ABC (A Better Chance) House. During those three months my views about life and college changed considerably. I met many different kinds of people, had a chance to experience "the real world," and perhaps more important, I had a chance to read books that were not assigned for a course. It was during this term that I decided that I definitely did not want to return to college in the fall; in August I officially withdrew from Dartmouth.

I did not drop out without a purpose. I stayed with the ABC program for the next academic year. In addition to five nights of tutoring each week, and the other obligations that accompany the position of resident tutor, I did some unofficial student teaching at Concord High School, worked as a part-time volunteer for a food co-op, and read many more books that I ever would have read in college. I think that this off-campus experience has been an essential part of my college career; in fact. I would have dropped out even if it had meant that I could never return to college.

Near the end of my year off I found thai I began to miss the academic world, and by June I had made arrangements for returning to Dartmouth. Now that I am back in the academic circle, studying seems much more pleasant than it did during my first two years. I no longer get bogged down in studies; I don't feel the dissatisfaction that I used to feel. I enjoy life more, I feel more relaxed.

But words cannot adequately express the experience. I would strongly encourage anyone who is even slightly discontented with his/her college situation to drop out for a while. It can make all the difference in the world.

#PETER B. KINGSLEY '74

...for various reasons.

One day, as I was walking through Baker, an idea for a short story erupted in my head. I stopped immediately took some copy paper out of my pocket, and made a note of the idea. On a similar occasion the title for an anthropology term paper popped into my head. I stopped at the same spot near the card catalogue, and made a note of it this time in the pocket notebook I always carry.

The note for the story was made in the fall of 1935, my sophomore year. The note for the term paper was made in the spring of 1972, the year before I was to receive my A.B. at Commencement in front of Baker. During the long interval, I was to make thousands of notes for all kinds of writing.

When I got the idea for the short story, I put it down on "copy paper" - the kind of paper newsmen write their articles on because, as a New York Times man, I had already developed the habit of always having some of it in my pocket. I had had a summer job at the Times between my freshman and sophomore years, and the following two summers, and that committed me to writing. There were other circumstances: the depression and my others death at the end of my freshman But writing was it. I left Hanover before completing my senior year and have been writing ever since.

I knew that Gertrude had told Ernest at journalism would ruin his chances in fiction, but I didn't stop to analyze what she said. I stayed at the Times for 15 years because was continually stimulating, for almost standard reasons: one of the personages I got to know is now the King of Saudi Arabia; and there were many pleasant chats with T. S. Eliot, the Roosevelts, Lauritz Melchior and the like; I saw the Navy's first jet aerobatic team in action, wrote an article about 500-mile-an-hour artistry in the sky and after a year of red tape was the first writer to make a supersonic flight. I had by-line stories from Iceland, Turkey, Morocco. ...

Yes, it was too much fun. But finally, after a decade and a half, I left the Times to become a public relations director and later a magazine editor.

But what about that degree I had never gotten? Did that bother me when I was writing a book review or doing an interview in Paris? Yes, every minute, and I could fill this magazine with the details of the reasons. But mission unaccomplished will have to suffice, in a lame way.

In 1971, I returned to Hanover permanently and, happily, became a student again, with much help from Deans Terry and Brewster. As an English major I had never been able to work a course on Shaw into my schedule and it seemed like an intellectual black hole. My first course as a middle-aged undergraduate was on G.B.S. and it isn't possible that any of the other students got more out of the course than I did. I'll claim the same for the courses I took on African art and anthropology of India.

Was it weird to be among student-age students and professors years my junior? It was weird. But it didn't seem to bother anyone and I'll never give up studying. "If I were to do it all over again," I'd again major in English and learn all I possibly could about geology, art, anthropology, astronomy, botany. ...

Taking the courses I did - which, I guess, required some kind of effort and personal drive - completed the requirement for my A.B. Perhaps I should pose the question about whether there was any specific gain. Again, I could write at length attempting an answer. This will have to do: I had already spent a year in India but had learned little about that complex country. The anthropology course on India was a feast! When I try wood carving, I feel that I know intimately the thoughts of Africa's earliest sculptors. My general plans include a trilogy based on Hanover and what I learned about Shaw will in some way be reflected in the three novels. But those facts are unimportant. Even if it's platitudinous to word it, I'll say that what is important is to be back in Dartmouth.

BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureManin the Red Flannel shirt

January 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureNugget to Times Square

January 1974 -

Feature

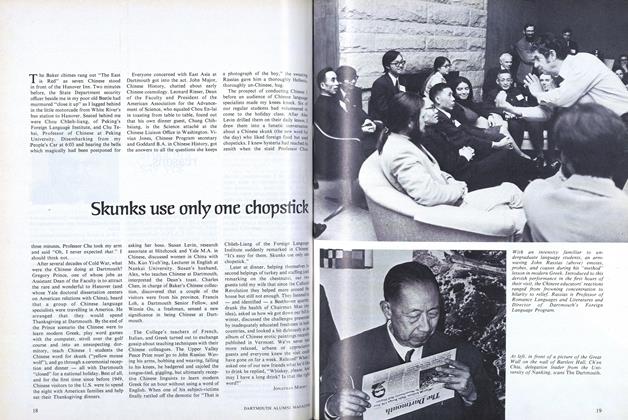

FeatureSkunks use only one chopstick

January 1974 By JONATHAN MIRSKY -

Feature

FeatureWolf-winds at the Doorways

January 1974 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

January 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleERNST SNAPPER

January 1974 By R.B.G.

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobert Lincoln O'Brien 1891

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Cover Story

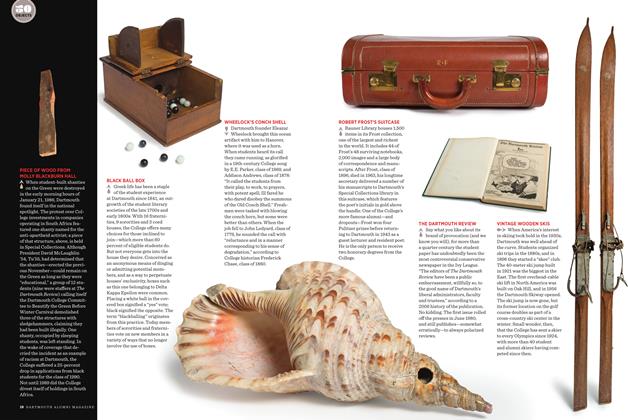

Cover StoryTHE DARTMOUTH REVIEW

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

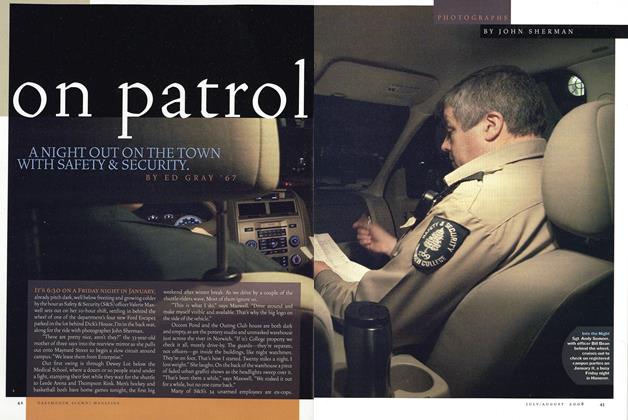

FeatureOn Patrol

July/August 2008 By ED GRAY ’67 -

Feature

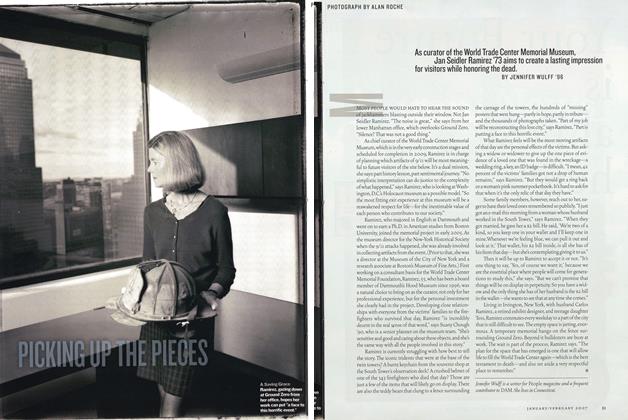

FeaturePicking Up the Pieces

Jan/Feb 2007 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

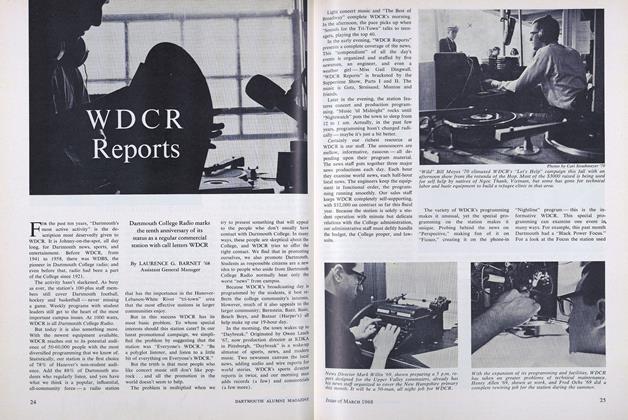

FeatureWDCR Reports

MARCH 1968 By LAURENCE G. BARNET '68 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMy Grub Box

APRIL 1997 By Vivian Johnson '86