By Albert William Levi '32. The Universalof Chicago Press, 1974. 327 pp. $12.50

Though primarily a contribution to the history of philosophy, this interesting work makes its major contribution to the sociology of knowledge. Levi is concerned to show that philosophical notions are not free-floating pieces 0f metaphy; sical truth, the character of which is unrelated to their temporal existential situation but rather "dated reflections of the time and social contexts in which they originate." The detailed and rich exposition attempts to document and justify this sociological thesis.

Levi does not proceed by generalizations or abstractions, but chooses to document his position by studying the philosophical Sitz in Leben of four philosophers from four historical periods: Plato, Aquinas, Descartes, and G.E. Moore, with glances at a fifth, Immanuel Kant. Plato represents the "age of the aristocrat"; Aquinas, "the age of the saint"; Descartes "the age of the gentleman." Kant is viewed as ushering in the "age of the professional," the paradigm of which is G.E. Moore.

For Levi, the outstanding characteristic of "the age of the professional" which impresses itself first upon Kant's thought and then upon that of Moore is that, elitist in its unconcern for the genera! educated populace, it aims only to interest and meet the standards of a small group of specialists concentrated in universities. The reasons, Levi believes, are social and historical rather than logical and philosophical. Accordingly, Moore's "fatherhood" of modern British linguistic-analytic philosophy is tied to and reflects late Edwardian Cambridge with its peace and tranquility. Moore's paradigmatic concern with analysis rather than ideas, with method and argument rather than content and inspiration, are seen to reflect the pre-First War social isolation of Trinity College, Cambridge, which allowed young men to pursue philosophical inquiry independently of larger societal, religious, or utilitarian considerations. Such a surrounding cultivated a philosophy devoid of urgency or passion and responsible for a unique analytic style obsessed by linguistic clarity, which Moore, with Bertrand Russell, was responsible for beginning.

There are weaknesses in Levi's thesis and specific issues, but the critical debate belongs to "professional journals" which Levi rightly associates with modern philosophy. Philosophical argument may well be culturally dependent in many ways, but another side not so temporally and historically bound requires other than socio-historical investigations. None-theless, this book is arresting and impressive.

Dartmouth Assistant Professor of Religion, Mr.Kalz teaches a course in Modern JewishThought and a seminar in PhilosophicalTheology. During the fall term he is active inEngland on the Dartmouth Foreign Study Plan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

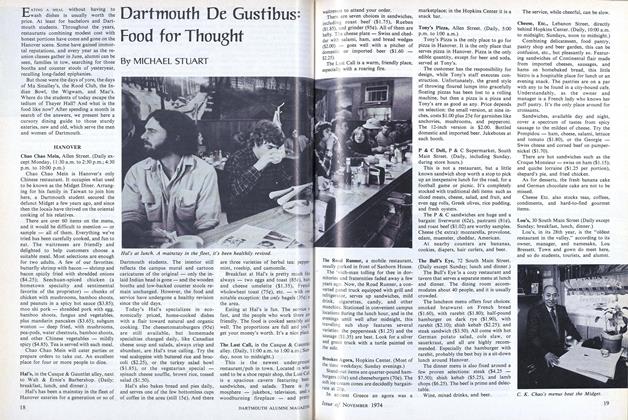

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: Food for Thought

November 1974 By MICHAEL STUART -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

November 1974 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

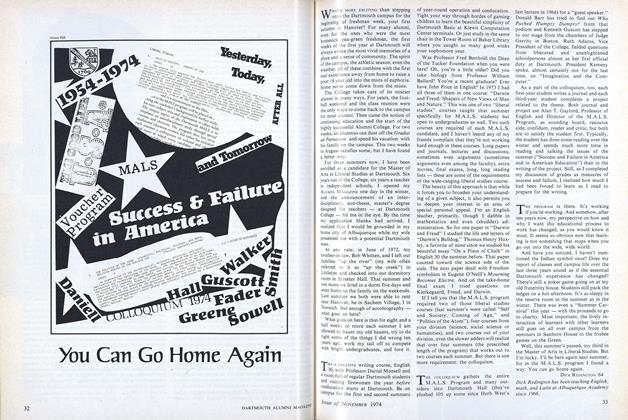

FeatureYou Can Go Home Again

November 1974 By DICK REDINGTON '64 -

Feature

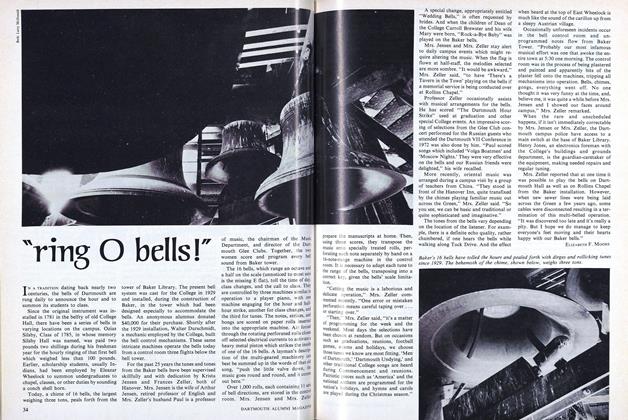

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1974 By JACK DtGANGE -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

November 1974 By J.H.

Books

-

Books

BooksAmerican Trade Unionism

February, 1924 By E. B. W. -

Books

BooksWHERE THERE'S SMOKE,

April 1947 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksYESTERDAY'S RULERS: THE MAKING OF THE BRITISH COLONIAL SERV ICE.

OCTOBER 1963 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksHALL'S LECTURES ON SCHOOL-KEEPING

MARCH 1930 By R. A. B. -

Books

BooksMountain Man

October 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksDEMOCRACY FIGHTS: A HISTORY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE IN WORLD WAR II

May 1951 By WAYNE E. STEVENS