Since a principled society's response to unprincipled acts of terror — and the price it is willing to pay to maintain its principles — is an issue over which honest people differ honestly, we asked eight distinguished attorneys and a career diplomat with a very personal stake in the problem to comment on Joseph Bishop's discussion of a democratic society's defense against terrorism.

I am not an expert on terrorism. However, it is a subject of more than academic interest to me. I have been the specific target (thankfully not the victim) of terrorist threats and for most of the past five years have lived a life circumscribed by bodyguards, armored cars, security devices, varying routes to work, and the rest of the paraphernalia now commonplace in my profession. That these are no ultimate guarantees of protection is clear from the fate of a number of my friends and colleagues in our and other diplomatic services. My motivation to understand the phenomenon is powerful.

Professor Bishop's contribution to the definition of terrorism is useful. I agree that the purpose of much terrorism is to force governments to adopt measures so repressive that they will lose popular support. I believe this was the principal objective of the Turkish terrorism that cost thousands of Turkish and eight American lives during the years I was ambassador there. It is possible that Pakistan will see a similar escalation in the period ahead.

The problem in international discussions of terrorism is that there is so much subjectivity surrounding it. One man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter, depending on the degree of your sympathy with his objectives. The Afghan mujaheddin are one thing to us, the other to the Soviet armies there. The techniques they use are no different from the anti-government insurgents (or1 are they national movements?) in El Salvador or South Africa or Spain. The methods of the P.L.O. are little different from those of yesteryears Stern Gang and Irgun Zvei Leumi. The Red Brigades, the I.R. A., the various Armenian groups, and others use many of the same methods — the almost random use of violence to instill horror and fear for less well-defined political ends.

When I was director of intelligence and research in the State Department, I asked for a list of all the groups that could be called terrorist or national liberationist depending on your perspective. As I recall, it numbered over 200. How do you cope wjth this confusion? Professor Bishop dispels some of it by suggesting two criteria: violence is terrorist when it is indiscriminate in its targeting and/or when it takes place in circumstances that offer effective peaceful methods for redress of just grievances and achieving change. Unfortunately, this still does not eliminate all imprecision and subjectivity in deciding what is terrorism and what is something else. Perhaps it is impossible. While P.L.O. and I.R.A. targeting certainly seems politically counterproductive, its indiscriminacy may lie in the eye of the beholder.

I agree with Professor Bishop's basic prescription for dealing with terrorists of the hostage-taking variety, an unvarying policy of never bargaining except to persuade surrender or to gain time for other action. I agree also with his criticism of the handling of the Iran hostage situation. I argued at the time that we should declare that an act of war had been committed against us, that we had no alternative to considering ourselves in a state of belligerency, that all Iranians in the U.S. not requesting political asylum be interned and all assets seized until Teheran had sorted itself out and a "prisoner exchange" removed the casus belli.

For an American abroad who may be the target of terrorist action the best security lies in accepting the disagreeable carapace of protection designed to deter or make it more difficult. If these fail, the hope must be that the host government will, through a combination of good intelligence and good police work, succeed as Italy did in the rescue of General Dozier.

There will be cases in which skillful negotiation will have a role, but capitulation should not, in my view, be even a last resort.

U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat keeps them going? A 'Mystic Glue' Perhaps

May 1982 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Feature

FeatureTerrorism and the Niceties of Justice

May 1982 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. -

Feature

FeatureImpacts simply positive

May 1982 -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

May 1982 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1964

May 1982 By Alexander D. Varkas Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

May 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Arts

JANUARY 1929 -

Article

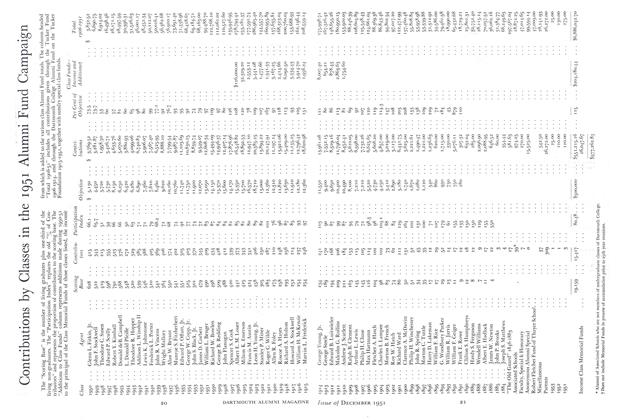

ArticleContributions by Classes in the 1951 Alumni Fund Campaign

December 1951 -

Article

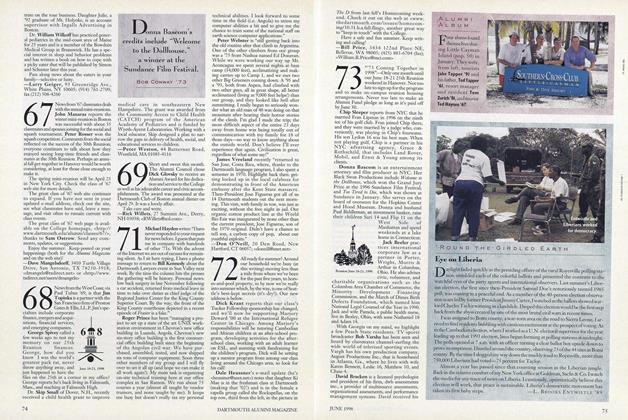

ArticleAlumni Album

JUNE 1998 -

Article

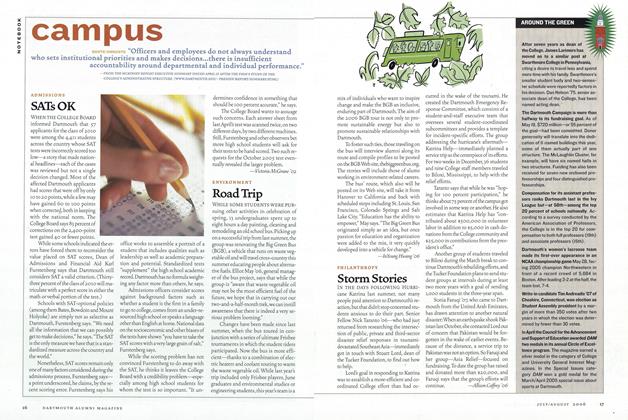

ArticleStorm Stories

July/August 2006 By Allison Caffrey '06 -

Article

ArticleSongs of the Dead

May/June 2004 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Article

ArticleReligion on the Campus

December 1934 By The Editors