THE GRASS around the house had already, now in early June, become too tall for Kristal’s brothers to hack it down with the push-mower, though they brandished it on its hind wheels like a whirling shield, and now they would have to do it with corn knives. Her aloof bearing, the sharp animal contrast of her brown hair with her pale skin, made her more a thing of the fields and woods around the house, than of the bleak brick crumbling house itself. The door when she pushed it open made a whoofing sound. Her dad and the boys, when the winter came, when the first snow had already blown, sealed the house down tight, doing this one thing well, covering the north wall outside with a blue tarp against the coldest winds, the windows sealed with plastic, foam sheets in the frames inside, making the house dark as a cave, intensely warm from the woodstove all winter, and still now too warm, no draft coming in. Her two brothers were sitting at the kitchen table, while something bubbled on the stove.

“What’s that?” she asked.

“Pea soup. Dad got a crate at the dollar store. Just the cans are dented.”

The two boys, twins, looked feral, their white-blond hair badly cut by their father, roughly, so that their ears bled with scissor nicks when he did it. Pale skin, living in this cave. Eleven years old, and already in trouble at school. Ashtrays filled with twisted butts and beer cans, empty cigarette packs, covered every flat surface in the room, except an area cleared for cooking, the interior furred with debris, as if subterranean mushrooms were being grown on every horizontal surface. The best light in the room came from the TV in the corner, never turned off, only three channels from the expensive antenna Amel had rigged on a hill with money they didn’t have. His big easy chair that leaned back, the Barcalounger, the Beast they called it, faced the TV, but on the Saturday he would be at Augie’s Tavern. A red steel pole, a screw-jack, held up a beam in the middle of the room.

Going up the stairs, she inhaled the dirty heavy air, which to her seemed sweet, the air of going to sleep, of the house that she couldn’t escape, not before, and that had formed her refuge from the angularities and brightness of school and the outside world, where she had managed with such rigor to pass as someone clean and silent, moving through the corridors between classes without speaking to anyone, and protected from the bullying of her classmates by her icebound almost savage air, thin as she was, without breasts, wearing white blouses, washed too often, repelling the heavy-footed advances of the boys who in her senior year belatedly recognized her apartness as beauty. At thirteen she had painted her room bright colors, pink and pale blue, and every summer would plan to repaint it white; but didn’t finally, knowing that she would leave when she could, and never again sleep in this room. She kept it immaculate, another reproach to her family, another element in her fantasy of her own separateness. Sitting cross-legged on her bed, she looked out the window. This had been her entire world, this view up the valley, up into Pedretti’s long rich pasture. A day like this could reconcile her to the room, if not to the house. From today she would be living in town, a place she barely knew, because her family skirted it, rejected its order, embracing an outlaw secrecy, outlaw pride, her father and the boys poaching deer, picking through other people’s posted woods, fishing their ponds secretly, trapping coon and otter, muskrats, living on welfare checks and handouts from the churches, a turkey at Thanksgiving, cheap toys for the children at Christmas. Everything she wanted from this room fit into the two cardboard boxes that she slowly packed, fetching them up from the cool earth-smelling basement, a few jeans, the right ones that she bought with her own money, Levis from the big stores on the highway to Madison, the Royall jacket, the plush toys that a boy won for her at the fair, the fur still clean two years later.

She went into her mother’s room, one of the boxes held protectively in front of her.

“I’m leaving,” she said. Her mother lay on the bed, enormous, in a ragged pink bathrobe, reading a book cross-eyed. She lived through boxes of romances that she bought from the Piggly Wiggly, where they more or less stocked them for her, her and a few others. Along one wall were the discarded books, piled neatly as if she were filing them after use, and along the other, empty jugs of fortified wine, which she said didn’t get her drunk. When the room filled up Kristal would help her, carry the bottles to the back and throw them in the ravine, and box the books to be sold at the second-hand store.

“Where you going?”

“I’m leaving. I got a job.” Kristal could see she was pretty bad.

She rolled over and sat up, her bare feet enormously veined and swollen. “Wait till your dad finds out. He’ll belt you good.”

“Not any more he won’t.”

The mother took a book from the floor, leaning down heavily, almost toppling to the side. “You want this one? It’s pretty good, I just got done with it.” Kristal and her mother had shared these books for years, the romances.

“Thanks Ma.”

“Tell me if you like it.”

“I will.”

A cunning conspiratorial look came into her mother’s eyes. “You’re cuttin’ out, aren’t you. Wait till your dad finds out.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

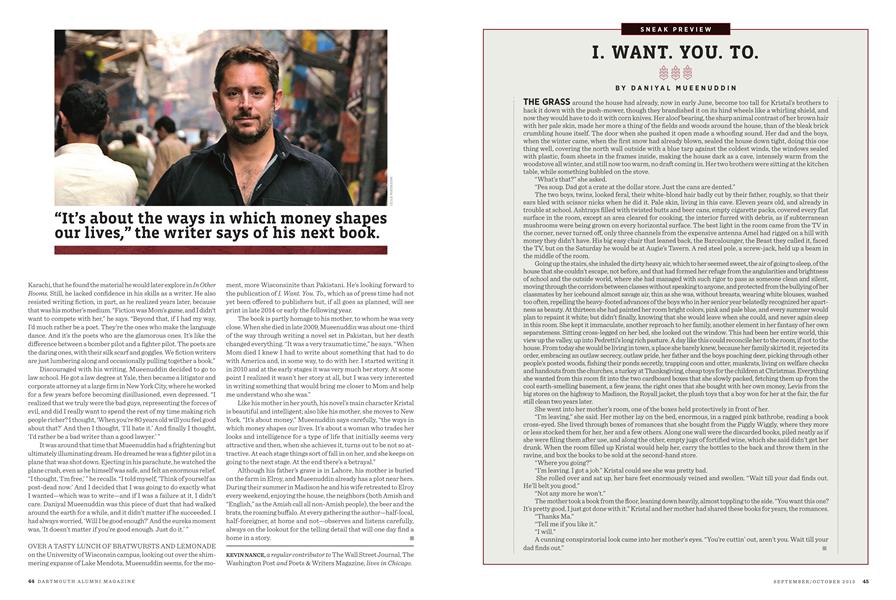

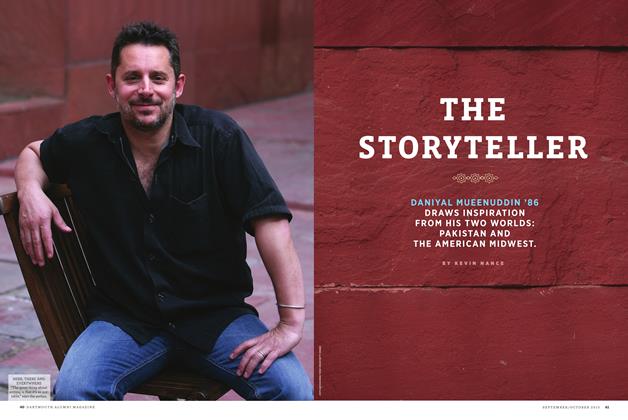

Cover StoryThe Storyteller

September | October 2013 By KEVIN NANCE -

Feature

FeatureModern Family

September | October 2013 By ALEC SCOTT ’89 -

Feature

FeatureThe Surrogacy Option

September | October 2013 By Lisa baker ’89 -

Feature

FeatureClass Notes

September | October 2013 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2013 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE -

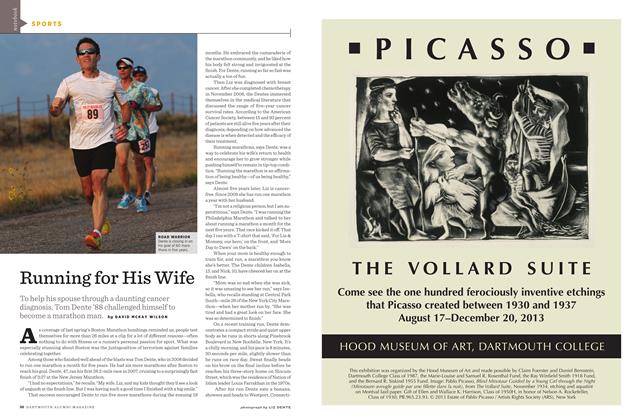

Sports

SportsRunning for His Wife

September | October 2013 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON