New approach to playgrounds may get kids to forget the swing set and monkey bars.

Dan Schreibman ’86 Caroline Choi ’90

ABOUT A DECADE AGO SCHREIBMAN was looking to build a play set for his older daughter. he wasn’t inspired by the choices—the familiar slide-swing combo, the wooden fort, the pirate ship. “All of the product was exactly the same, and not particularly attractive,” Schreibman tells DAM. “i wasn’t moved.” eventually, the management consultant settled for a tradi- tional set, but through the years he noticed

Sam Stein ’04 liz GanneS ’04

eSther cohen ’79 DiarmuiD o’connell ’86

Peter heller ’82 that his daughters spent little time using it, preferring instead to make their own fun with cardboard boxes or by the pond in the family’s new Jersey back yard.

A thought began germinating: How could he cre- ate a playground that fosters the creative play kids seem to enjoy most? Schreibman eventu- ally launched Free Play, a new studio that has developed a line of abstract struc- tures that look more like art than play- ground. Although studies have found that playing with unstructured materials such as tires, blocks and sand can be beneficial for a child’s social and intellectual growth, standard American playgrounds tend to be sterile and prescriptive, Schreibman says. They’re designed to avoid litigation and injury rather than foster creativity. “i wanted a playground that looked like nothing you’ve ever seen before,” he says. “So the idea became this sort of sculptural art that also provides children with as many sensory experi- ences as possible, with no functionality to the equipment.”

True to Schreibman’s intentions, Free Play’s four play structures don’t resemble anything you’ll find in a school- yard—yet. The pieces, which cost $30,000 to $55,000 each (about 50 to 65 percent more than traditional structures), can be arranged individually or together. There is the Maze, a boxy blue structure filled with holes, like giant cubes of Swiss cheese, that can be adjusted and arranged like blocks. The Weeping Willow consists of a dense canopy of brightly colored ropes dangling down to swing from or climb on. Cornstalks is a similar concept, except the 6.5- foot tubes stick up from the ground and gently sway when brushed against. Finally, there is the Ant Farm, a massive polycarbonate structure that supports suspended climb- ing tubes to scramble around or hide out in. “They are all very much climbable structures,” Schreibman says. “We used a lot of interesting textures and surfaces to really make it an experience. It creates open spaces where kids can hang out and play.”

designing playgrounds is a major change of pace for the Dartmouth religion and goverment major, who has spent two decades working as a consultant, and until recently had never worked in design or landscape architecture. “i probably missed my calling,” Schreibman says. “but at least i found it later in life.”

Despite his lack of formal training—and with help from new York city-based LTL Architects—Schreibman’s idea has taken off. After launching in 2013, Free Play debuted its first playground this spring at a new FIFA soccer stadium in the United Arab Emirates. The studio has about two dozen other projects, primarily for commercial spaces, in the pipeline. Educators, he says, are particularly excited about the project. “They feel like we are filling a much- needed gap,” he said. “it’s never going to replace traditional playground equipment, but where there is interest, the interest is tremendous. it’s just a lot of fun.”

Schreibman’s Ant Farm: a sensory experience. <<<<

Laura

GRACE WYLER is a journalist based in New York City.

“If you let a child develop that love of learning and exploration, it will last them a lifetime.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURE

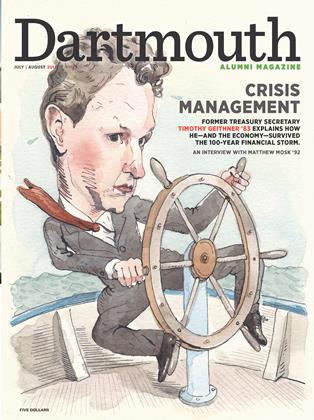

FEATUREPar for the Course

July | August 2014 By RICK SHEFCHIK ’74 -

Feature

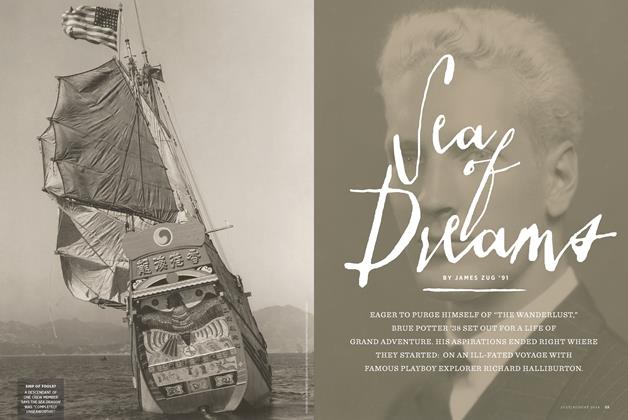

FeatureSea of Dreams

July | August 2014 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

THE DAM INTERVIEW

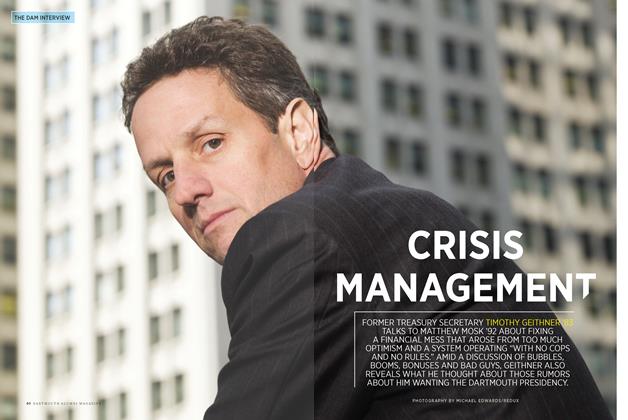

THE DAM INTERVIEWCrisis Management

July | August 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYNothing In Common

July | August 2014 By LYNN HOLLENBECK ’83 -

RETROSPECTIVE

RETROSPECTIVEOpportunity Knocks

July | August 2014 By CHARLES DEY ’52 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWall Papers

July | August 2014 By LISA FURLONG