G ENERAL MANA G ER , DARTM O UTH O UTIN G C LUB

Gawler, who doubles as assistant director of the outdoor programs office, has been building fires for a long time. Charged with overseeing the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge and various outdoor PE classes and clubs, the former competitive fire builder (yes, there is such a thing) started camping at age 9. “Fire has always fascinated me,” he says. “Once I started to learn about the science, that only increased my interest.” Here he outlines the do’s and don’ts of building a campfire—and why you should do so with caution.

BE SMART Although the “leave no trace” philosophy dis- courages fire-building, when they are neces- sary, campfires should be started only where there has been some rain. If you build a fire pit, start by “digging away all of the organic material so you can get mineral soil, and then pile some rocks up around that to make a little ring. It’s very important you not get those rocks out of a river, because if they’ve been soaked with wa- ter and you then heat them up really hot, they can explode.”

USE YOUR TONGUE For tinder, start with pencil-sized pieces of wood. They provide “more surface-area- to-volume ratio, which means the tinder can heat up fast enough to combust before you lose the heat.” This wood can either be cut or collected from the ground, but make sure that it’s dry. Two good methods to test for this: See how easily the wood snaps—if it is rot- ten or too fresh, it will just bend—or stick your tongue on it. “If it’s dry, your tongue will stick to it a little bit. If it’s wet, it will feel cold.” PICK AN OPTION “There are two old methods to building a fire: a teepee, where you’re making a cone- shaped thing with your tinder underneath it and the kindling on top; and a log cabin, where you put a pile of tinder in the middle and you alternate the kindling like Lincoln Logs on top.” Gawler suggests a combina- tion of the two. “You need to make sure that the pile is spread out enough for air to flow in, but not so spread out that the heat doesn’t transmit between each different piece.” Then you can begin adding wood that is “thumb-thick,” then “wrist-thick.”

ALWAYS EXTINGUISH Gawler emphasizes the importance of putting your fire out thoroughly. “If you had a sizable fire, then the coals in the middle of that pile are really hot. What you need to do is dump water on it, wait a few minutes, come with your nice heavy boot, kick it around a little bit until you find the very bottom of that pit and pour more water on it until you have wood ash and water slush. It’s very possible for campfires to burn underneath the ground and then, after you leave, pop out and start a forest fire.”

2,752 Number of objects from the Hood Museum’s permanent collection that were used in 111 lessons taught at the museum’s Bernstein Study-Storage classroom from the summer of 2014 through the spring of this year

“There’s little impromptu performance here. So this summer I decided, why not do something?” —Jett Oristaglio ’17, a cognitive science major who spent several weeks during summer term reading aloud from One Hundred Years of Solitude while sitting on the Green Q U O T E / U N Q U O T E

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

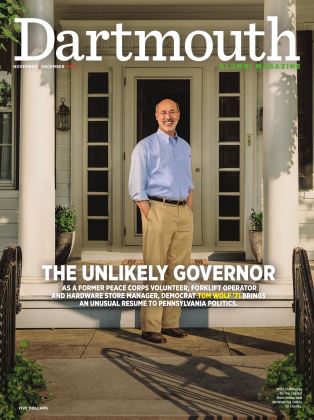

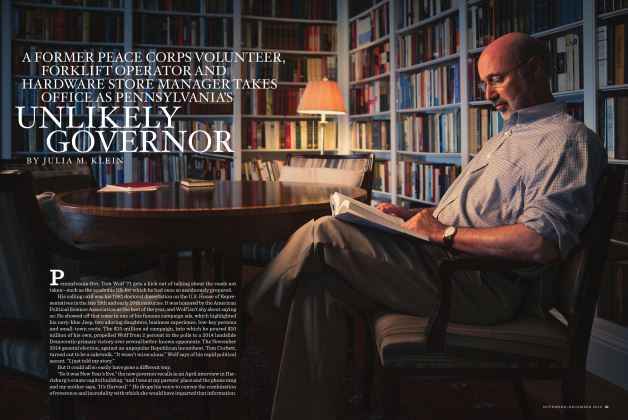

Cover StoryThe Unlikely Governor

November | December 2015 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

FEATURE

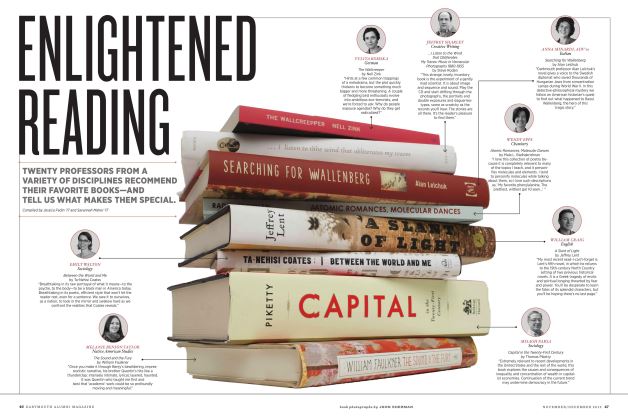

FEATUREEnlightened Reading

November | December 2015 By Jessica Fedin ’17 and Savannah Maher ’17 -

FEATURE

FEATUREMeanwhile, In Illinois

November | December 2015 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Feature

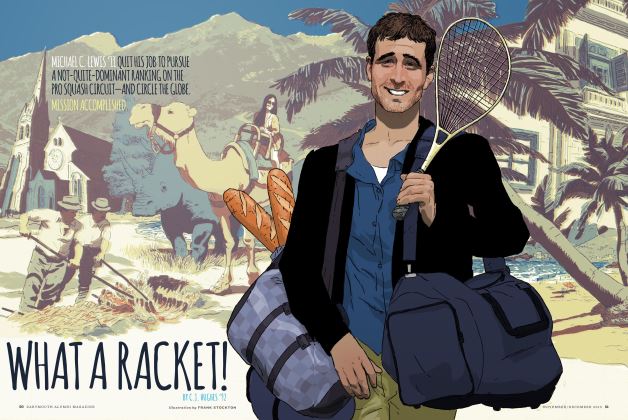

FeatureWhat a Racket!

November | December 2015 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

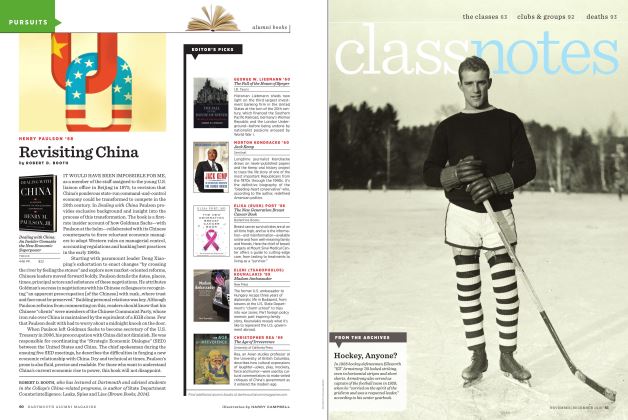

FeatureClassnotes

November | December 2015 By LIBRARY COLLEGE DARTMOUTH -

Feature

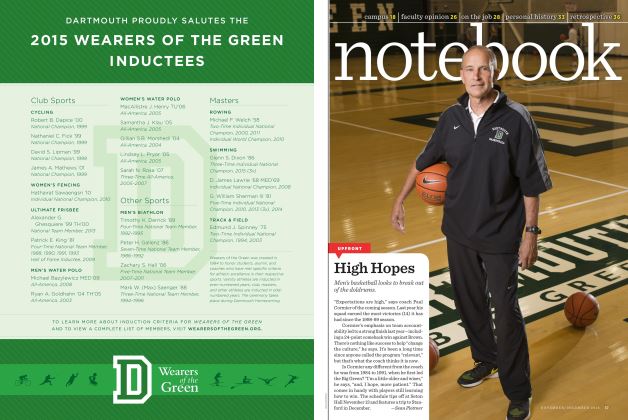

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2015 By SHERMAN JOHN

Marley Marius ’17

-

Article

ArticleHome Sweet Hogwarts?

NovembeR | decembeR By Marley Marius ’17 -

Article

ArticleStudents and Profs Seek Change

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Marley Marius ’17 -

Article

ArticleIn the Belly of a Beast

MARCH | APRIL By Marley Marius ’17 -

FEATURE

FEATUREHorse Power

MAY | JUNE By MARLEY MARIUS ’17 -

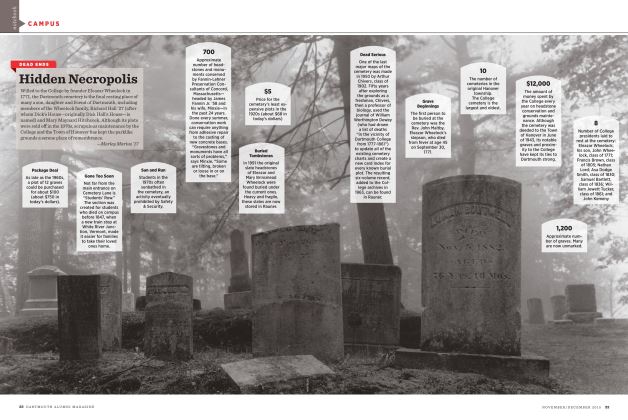

CAMPUS

CAMPUSHidden Necropolis

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By Marley Marius ’17 -

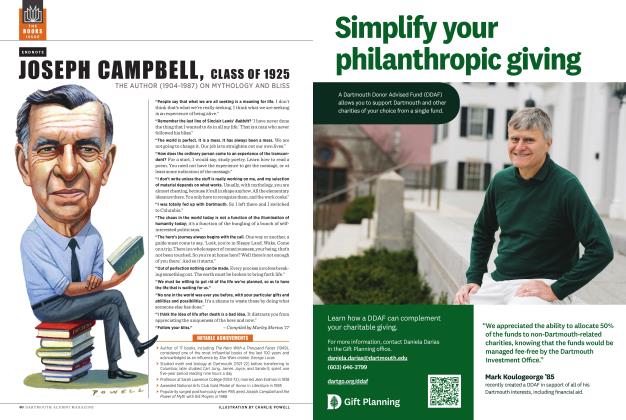

Features

FeaturesJoseph Campbell, class of 1925

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Marley Marius ’17