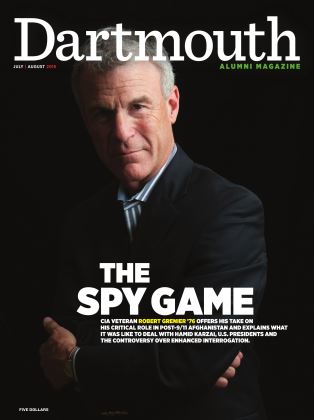

The Chosŏn One

The influence of Homer Hulbert, class of 1884, lives on in a country far from his home.

JULY | AUGUST 2015 KARL SCHUTZ ’14 and JUN BUM SUN ’14The influence of Homer Hulbert, class of 1884, lives on in a country far from his home.

JULY | AUGUST 2015 KARL SCHUTZ ’14 and JUN BUM SUN ’14The influence of Homer Hulbert, class of 1884, lives on in a country far from his home.

We’ve all been there—sitting in class in Dartmouth Hall, looking wistfully outside. Now imagine looking out and seeing a group in traditional Korean dress, parad- ing across the Green.

The rest of his life unfolded in a much less predictable way.

Two years after graduating from Dartmouth Hulbert left his studies at Union Theological Seminary in New York, where he was preparing for missionary work, and traveled halfway across the world to Korea. He had been invited by fellow Dartmouth alum and commissioner of the then U.S. Bureau of Education, John Eaton, class of 1854—a friend of his father’s—to help set up an English language school in Seoul. It was to be the first of its kind in the country.

That scene likely happened in the fall of 1883, when the first official Korean delegation to the United States toured the East Coast, including a one-day stop at Dart- mouth. It’s a relatively obscure moment in the College’s history, but one that marks a great jumping off point for the story of Homer Hulbert, the great-great-grandson of Eleazar Wheelock. Hulbert was begin- ning his senior year at Dartmouth. He had grown up nearby in Vermont and had made the expected college choice.

Once in Korea, Hulbert dedicated himself to learning the country’s language and history. He found the simplicity of its phonetic alphabet, Hangul, extraordinary. While the country’s elite at the time wrote

exclusively in Chinese characters, commoners used Hangul, which was created in the 1400s during the Chosŏn Dynasty. Hulbert believed that Hangul’s accessibil- ity could improve literacy and empower the people.

As part of his belief in the democratizing power of Hangul, in 1895 Hulbert published Samin P’ilchi, a gazetteer of the world, the first textbook written entirely in the Korean alphabet. Ten years later, in 1905, he published in English his History of Korea, the first comprehensive history book on Korea written by a foreigner with direct access to Korea’s imperial archives. (Original copies of both books are available in Rauner.)

Hulbert also proposed certain grammatical conventions that became important components of today’s Korean writing system: spaces between words, commas, periods and writing from left to right. One of his students, Ju Si-Gyeong, would go on to become a great modernizer of the Korean language, adapting many of Hulbert’s ideas to his mother tongue. Hangul went on to replace Chinese characters during the 20th century.

Hulbert’s prominence in Korea also put him in danger. When the Japanese assassinated Korea’s Queen Min in 1895 because of her anti-Japanese leanings, the remain- ing ruler, King Kojong, called on Hulbert to stand guard outside his residence in Gyeongbok Palace. The king thought the Japanese would not cross an American for fear of diplomatic retaliation.

In 1905 Hulbert yet again assisted Kojong, who was by then emperor. Shortly before Korea became a protectorate of Japan, Hulbert traveled to Washington, D.C., to deliver a personal letter from Kojong to President Theodore Roosevelt. The letter asked Roosevelt to intervene to free Korea from Japanese oversight, but the president ignored the request. Roosevelt had already made a covert pact with Japan, wherein the United States conceded Korea to Japan in return for Japan giving the Philippines to the United States.

Two years later, in 1907, Hulbert went on a secret mission for Kojong to The Hague. Representatives from countries around the world—except, notably, Korea—gathered there to draft a set of laws regulating the conduct of war. Hulbert accompanied three uninvited Koreans to ask the international audience to defend Korean sovereignty. The Japanese, however, blocked Hul-

bert and the Korean emissaries from speaking at The Hague. They also banned Hulbert from returning to Korea.

In the summer of 1949, after four decades of lecturing and writing about Korea and working with Korean independence activists in Washington, D.C., Hulbert re- turned to the country at the age of 86. Syng- man Rhee, a former student and the first president of the newly created Republic of Korea, had invited him to participate in a national celebration of Korean indepen- dence from Japanese rule.

Unfortunately, Hulbert died of pneumonia shortly after his return. Now buried in Seoul’s Yanghwajin Foreigners’ Cemetery, his tombstone reads, “I would rather be buried in Korea than in Westminster Abbey.”

In 1950 Rhee honored Hulbert with the republic’s Taeguk Medal, one of the highest official honors in Korea. Never before had it been awarded to a foreigner.

Today Koreans remember Hulbert for his steadfast commitment to their country at a time when the Western world seemed united in its support of Japan.

In July 2013 the Korean Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs named Hulbert the “Independence Activist of the Month.” Posters with his name and face adorned Seoul’s subway system. Again, he was the first non-Korean to receive such an honor. In 2013 the Seoul metropolitan government acknowledged Hulbert’s con- tributions to the Korean language, install- ing a statue of Hulbert, standing alongside Si-Gyeong, in its downtown. In October 2014 the Korean government honored him with its highest cultural award.

Every August several hundred prominent Korean officials and guests gather in Seoul for the Hulbert Memorial Society’s annual service for Hulbert, the man re- membered in this observance as “Korea’s favorite American.”

It is a fitting description of an alum who, in 1929, wrote of his work in Korea, “I have been fighting for the rights and liberties of 18 million people whose love I hold as my most precious possession and whatever the outcome I deem that loyalty to such a cause is worthwhile.”

karl SCHUTZ is teaching English in Korea on a Fulbright grant. JUN BUM SUN is pur- suing a master’s in history at Oxford. Both served as interns with the Hulbert Memorial Society in Seoul in 2014.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURE

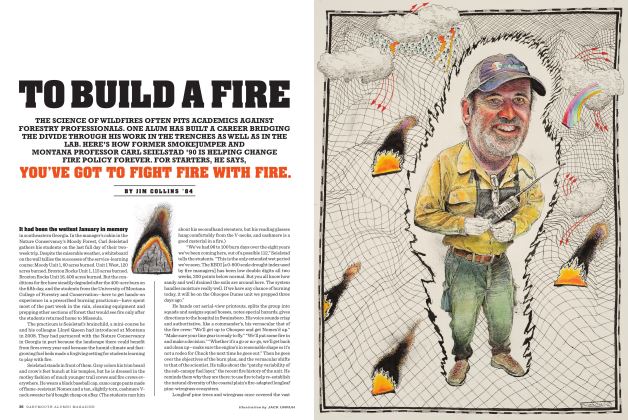

FEATURETo Build a Fire

July | August 2015 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

July | August 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08 -

Feature

Featureclassnotes

July | August 2015 -

Feature

Featurenotebook

July | August 2015 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLife Support

July | August 2015 By PETER BARBER ’ 66 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMInspired by Salvador

July | August 2015 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14

HISTORY

-

HISTORY

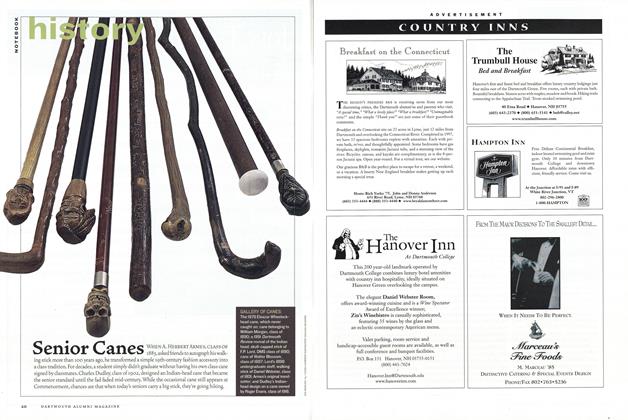

HISTORYSenior Canes

Mar/Apr 2001 -

HISTORY

HISTORYTies that Bind

May/June 2013 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

HISTORY

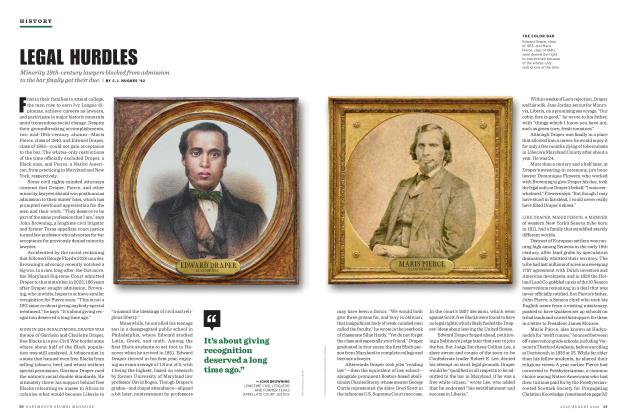

HISTORYLegal Hurdles

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

HISTORY

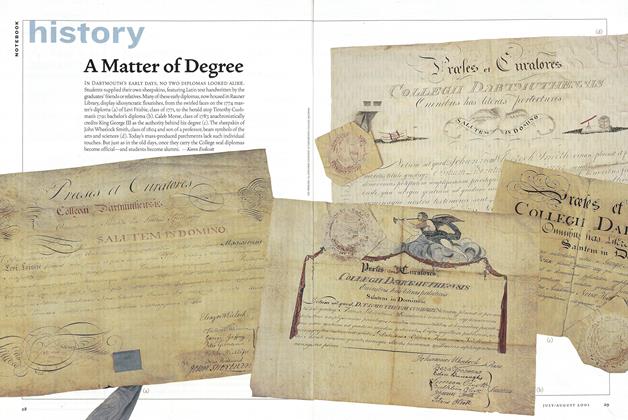

HISTORYA Matter of Degree

July/August 2001 By Karen Endicott -

HISTORY

HISTORYDéjà Vu All Over Again

Mar/Apr 2008 By Marilyn Tobias -

HISTORY

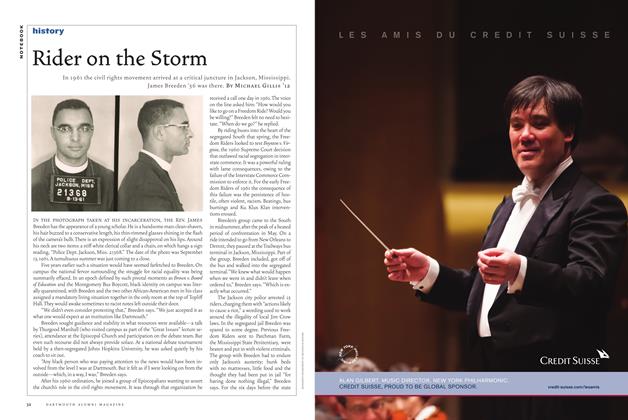

HISTORYRider on the Storm

Sept/Oct 2011 By Michael Gillis ’12