When Sara Hobel ’76 came to the Horticultural Society of New York as executive director in 2009, most folks still thought of it as a meeting place for affluent garden enthusiasts. Yet the “Hort”—founded more than a century ago with J.P. Morgan and Louis C. Tiffany among its original members—had built a roster of educational, vocational and therapeutic initiatives through the years, many of which help the underserved. “The organization had all these fantastic programs, but they had a very low profile,” says Hobel. “It was all kind of quiet.”

Since her arrival, the Hort has gained more recognition for its move toward social service, with eco-friendly activities that include restoring community gardens in disadvantaged neighborhoods, building urban farms at supportive housing facilities and providing horticultural training for the city’s at-risk youth and adolescents aging out of the foster care system. Hobel has also helped the Hort expand a small but longstanding program at the Rikers Island Correctional Facility. Today the program is on track to serve 500 inmates and detainees who tend more than three acres of herb, vegetable and native plant gardens and greenhouses on the prison’s grounds. Hobel says that the objective isn’t just to teach new skills but to help reduce recidivism by offering a constructive intervention. “So many of our participants grew up with violence and poverty. They come off the streets angry, traumatized and reluctant to appear vulnerable in the prison setting,” she says. “We see the transformative power of horticultural therapy play out over and over as our participants gain self-control, compassion and resilience through their joint efforts to cultivate the garden.”

Under Hobel’s leadership the Hort also created 14 gardens at public schools throughout Queens. There, students learn about nutrition by growing their own food, a novelty for those with limited access to fresh produce. “You’ve got to see these kids when they pull something like a carrot out of the ground for the first time,” she says. “They are children who literally have nothing in their neighborhoods but fast food.” The group partnered recently with New York City officials, local businesses and other nonprofits to install and maintain green spaces in public plazas throughout the five boroughs, located mainly in underprivileged areas. “They’re glorious,” she adds. “The planters look like those on Fifth Avenue.”

Hobel came to the Hort from the Wildlife Conservation Society, where she oversaw a range of education programs at the Bronx Zoo, Central Park Zoo and more. Before that, she served as director of the city’s Urban Park Rangers, who lead outdoor recreation, wildlife management and law enforcement services at New York’s flagship parks. Those positions marked a career shift for the former English major, who decided to change jobs in 1999 after more than 20 years of working in marketing and business development for publications such as The New York Times and Newsweek. Running conservation organizations is a good fit for Hobel, who wanted to connect with nature, yet enjoyed urban culture. “It took me a while to figure out you can have both,” she says. “It’s the perfect crossover.”

Heather Salerno

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FEATURE

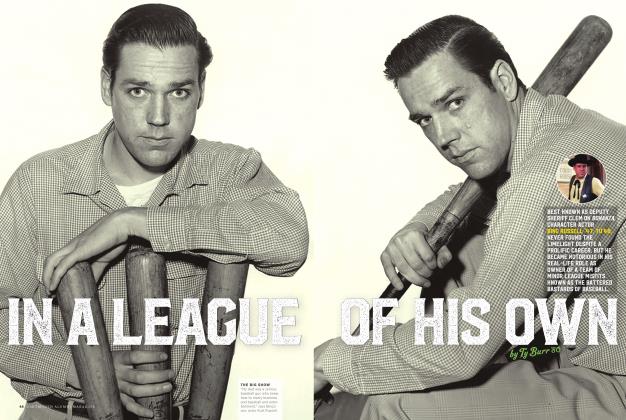

FEATUREIn a League of His Own

November | December 2016 By TY BURR ’80 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYKing of the Hill

November | December 2016 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

FEATURE

FEATUREDramatically Different

November | December 2016 By HEATHER SALERNO -

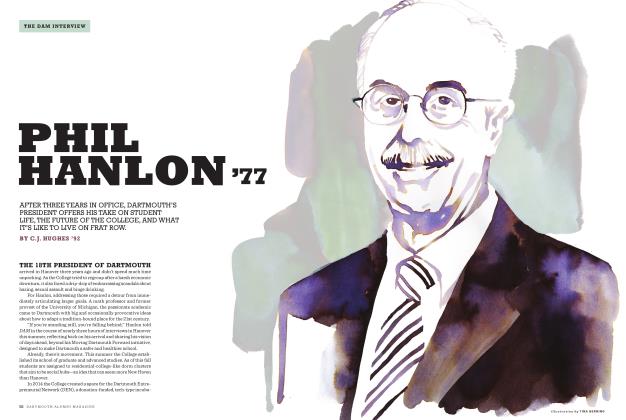

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWPhil Hanlon ’77

November | December 2016 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

RETROSPECTIVE

RETROSPECTIVETales of the Nugget

November | December 2016 By JESSICA FEDIN ’17 -

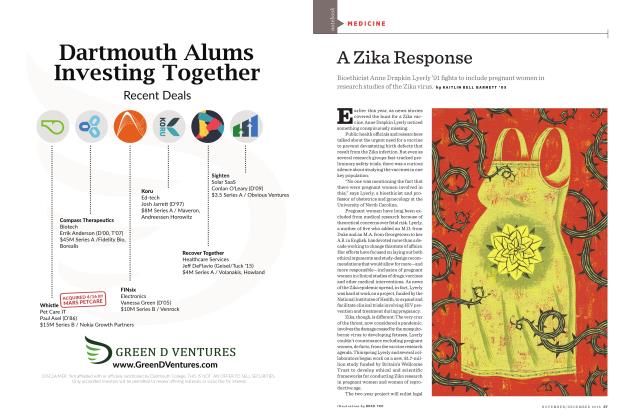

MEDICINE

MEDICINEA Zika Response

November | December 2016 By KAITLIN BELL BARNETT ’05

Voices in the Wilderness

-

Voices in the Wilderness

Voices in the WildernessTrue Stories

MARCH | APRIL 2021 By Abigail Jones ’03 -

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESS

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESSSea Changer

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Abigail Jones ’03 -

Voices in the Wilderness

Voices in the WildernessOn a Roll

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2020 By Christopher Cartwright ’21 -

Voices in the Wilderness

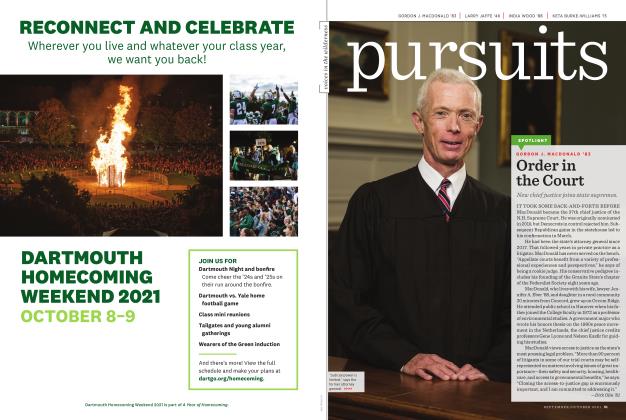

Voices in the WildernessOrder in the Court

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Voices in the Wilderness

Voices in the WildernessGood Education

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By Elizabeth Janowski ’21 -

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESS

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESSFighting the Good Fight

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By Heather Salerno

HEATHER SALERNO

-

FEATURE

FEATUREHat Couture

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By HEATHER SALERNO -

Pursuits

PursuitsOut of This World

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By Heather Salerno -

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBChateaux Faux?

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By HEATHER SALERNO -

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESS

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESSTuna Diplomacy

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By HEATHER SALERNO -

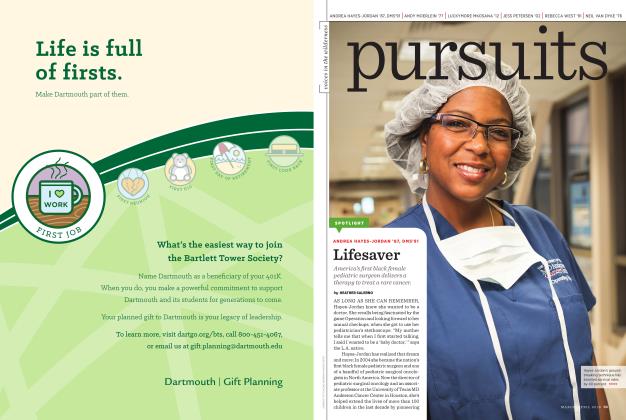

pursuits

pursuitsLifesaver

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By HEATHER SALERNO -

pursuits

pursuitsMotivated

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By Heather Salerno

Voices in the Wilderness

-

Voices In the Wilderness

Voices In the WildernessBrian Mann '02

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By David Holahan -

VOICES in the Wilderness

VOICES in the Wilderness“A Meditation”

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By Heather Salerno -

Voices in the Wilderness

Voices in the WildernessMinimalist Luxe

MAY | JUNE 2017 By HEATHER SALERNO -

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESS

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESSIndigenized Fitness

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By James Napoli -

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESS

VOICES IN THE WILDERNESSThe Mentor

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Voices In the Wilderness

Voices In the WildernessLeslie Jennings Rowley ’96

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By Lauren Vespoli '13