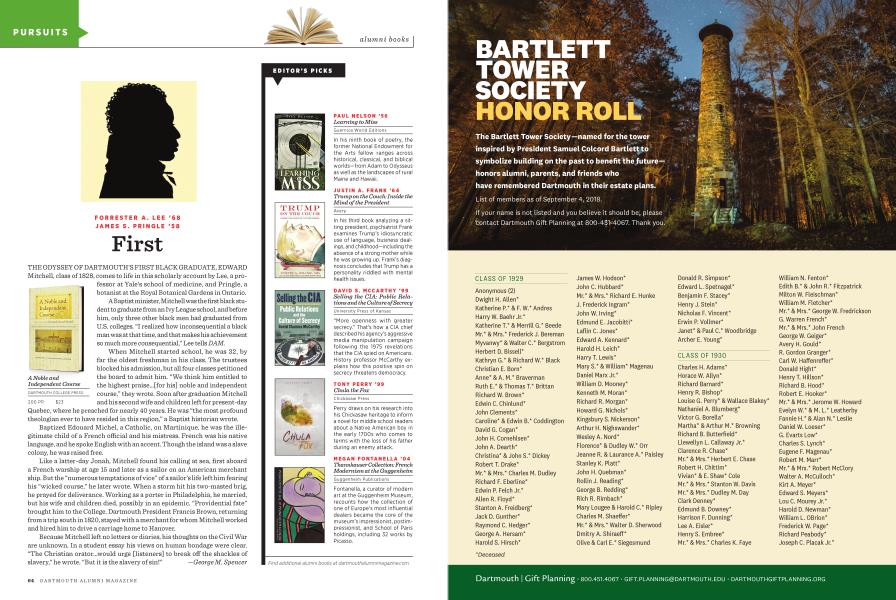

First

FORRESTER A. LEE ’68 JAMES S. PRINGLE ’58

THE ODYSSEY OF DARTMOUTH’S FIRST BLACK GRADUATE, EDWARD Mitchell, class of 1828, comes to life in this scholarly account by Lee, a professor at Yale’s school of medicine, and Pringle, a botanist at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Ontario.

A Baptist minister, Mitchell was the first black student to graduate from an Ivy League school, and before him, only three other black men had graduated from U.S. colleges. “I realized how inconsequential a black man was at that time, and that makes his achievement so much more consequential,” Lee tells DAM.

When Mitchell started school, he was 32, by far the oldest freshman in his class. The trustees blocked his admission, but all four classes petitioned the board to admit him. “We think him entitled to the highest praise...[for his] noble and independent course,” they wrote. Soon after graduation Mitchell and his second wife and children left for present-day Quebec, where he preached for nearly 40 years. He was “the most profound theologian ever to have resided in this region,” a Baptist historian wrote.

Baptized Edouard Michel, a Catholic, on Martinique, he was the illegitimate child of a French official and his mistress. French was his native language, and he spoke English with an accent. Though the island was a slave colony, he was raised free.

Like a latter-day Jonah, Mitchell found his calling at sea, first aboard a French warship at age 15 and later as a sailor on an American merchant ship. But the “numerous temptations of vice” of a sailor’s life left him fearing his “wicked course,” he later wrote. When a storm hit his two-masted brig, he prayed for deliverance. Working as a porter in Philadelphia, he married, but his wife and children died, possibly in an epidemic. “Providential fate” brought him to the College. Dartmouth President Francis Brown, returning from a trip south in 1820, stayed with a merchant for whom Mitchell worked and hired him to drive a carriage home to Hanover.

Because Mitchell left no letters or diaries, his thoughts on the Civil War are unknown. In a student essay his views on human bondage were clear. “The Christian orator...would urge [listeners] to break off the shackles of slavery,” he wrote. “But it is the slavery of sin!”

George M. Spencer

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

YOUR TURN

YOUR TURNYOUR TURN

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 -

notebook

notebookMagic to Live By

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By ROB WOLFE ’12 -

Photography

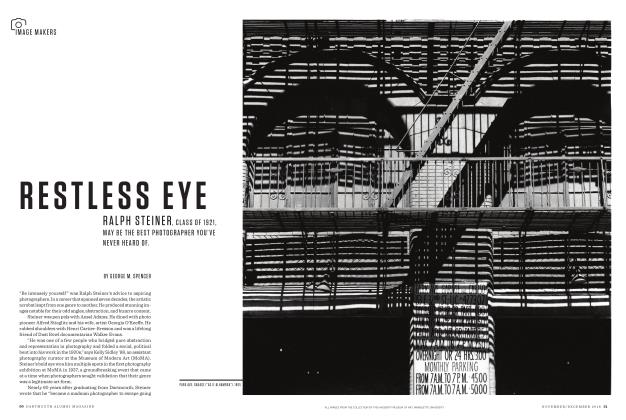

PhotographyRestless Eye

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBlood, Guts, and Beer

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By WILLIAM LAMB ’67 -

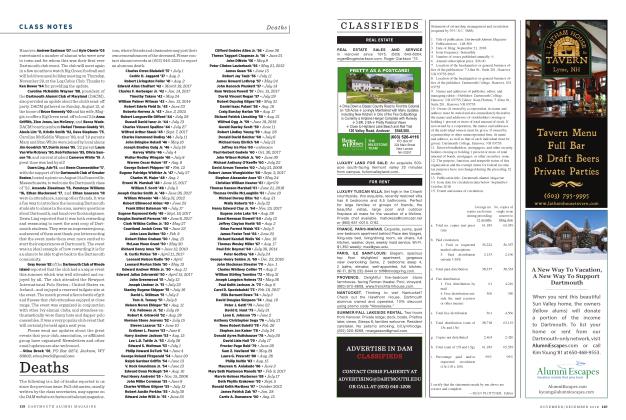

class notes

class notesDeaths

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 -

SPORTS

SPORTSThree-For-All

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By CHARLES MONAGAN ’72

George M. Spencer

-

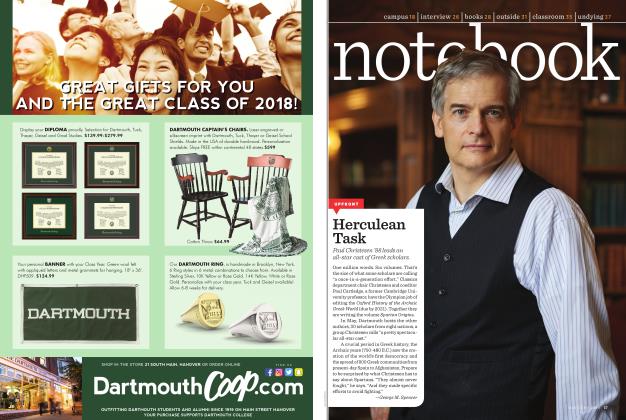

notebook

notebookHerculean Task

MAY | JUNE 2018 By George M. Spencer -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMA Body in Motion

MAY | JUNE 2018 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

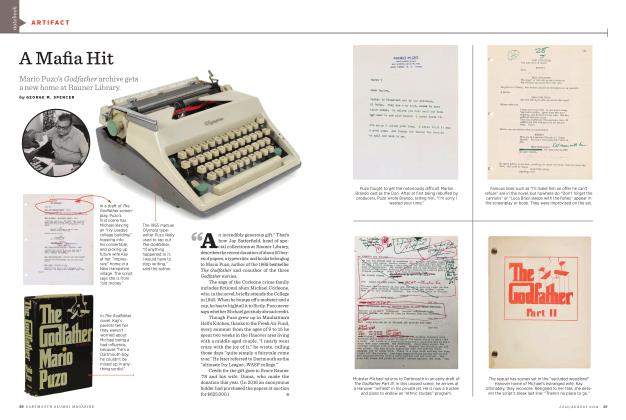

ARTIFACT

ARTIFACTA Mafia Hit

JULY | AUGUST 2018 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

PURSUITS

PURSUITSWild Thing

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2019 By George M. Spencer -

notebook

notebookLOOK WHO'S TALKING

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By George M. Spencer -

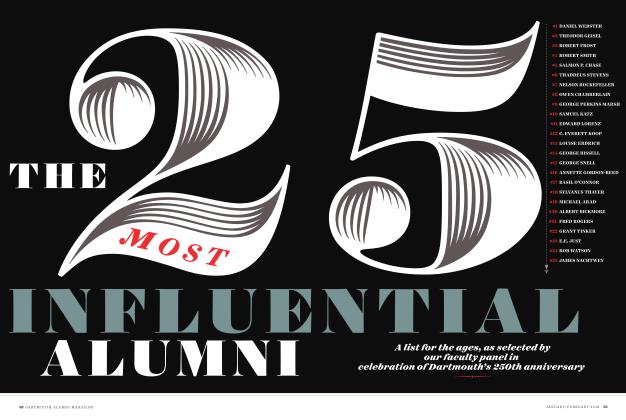

The 25 Most Influential Alumni

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2019 By Rick Beyer ’78, George M. Spencer, Jim Collins ’84, 3 more ...

Pursuits

-

PURSUITS

PURSUITSSARAH FRECH ’84 Saving lives, One Shot at a Time

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By Celine Choi ’26 -

pursuits

pursuitsMothers of Invention

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By Heather Salerno -

pursuits

pursuitsA Tough Test

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By Heather Salerno -

PURSUITS

PURSUITSFarsighted

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By Jimmy Nguyen ’21 -

pursuits

pursuitsBurning with Intrigue

JULY | AUGUST 2018 By Julia M. Klein -

pursuits

pursuitsKick the Habit

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By Sean Plottner