View Finder

Postdoc Jeff Kerby combines photography with storytelling to advance science and conservation.

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 James Napoli Jeff KerbyPostdoc Jeff Kerby combines photography with storytelling to advance science and conservation.

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 James Napoli Jeff KerbyOn a grassy plateau in the central Ethiopian Highlands, thousands of feet above the Great Rift Valley, Kerby discovered the power of images to enhance both research and storytelling. He traveled to the region in 2011 with anthropologist Vivek Venkataraman, Adv’16, to join scientists at the Guassa Gelada Research Project on an expedition to document the interactions of Ethiopian wolves and gelada monkeys, the world’s only grass-eating primates. Kerby returned from the National Geographic-funded trip with more than 20,000 photos, some of which he presented at the magazine’s headquarters in Washington, D.C.

“The senior natural history editor told me, ‘Don’t just focus on pretty pictures of monkeys. That’s not a story. Make sure you get behaviors—those are interesting.’ That advice stuck with me,” says Kerby. “You can’t just take a bunch of nice pictures and expect someone else to tell the story for you. That’s at the core of your job as a photographer.”

MONKEY SEE A family of gelada monkeys rises at dawn on a cliff in the Ethiopian Highlands. “The air is cold this time of day—close to freezing— but soon the alpine sun warms the highlands while the monkeys roam for grass,” says Kerby, who captured this image for National Geographic.

MONKEY SEE A family of gelada monkeys rises at dawn on a cliff in the Ethiopian Highlands. “The air is cold this time of day—close to freezing— but soon the alpine sun warms the highlands while the monkeys roam for grass,” says Kerby, who captured this image for National Geographic.

With the encouragement of photojournalist mentors and Nat Geo staff, Kerby continued to develop his camera skills in the field. He captured dramatic shots of gelada monkeys during moments of play, aggression, birth, rest, and death. After a few additional trips funded by National Geographic Society grants, his pictures were published in a feature article in the April 2017 issue of the magazine.

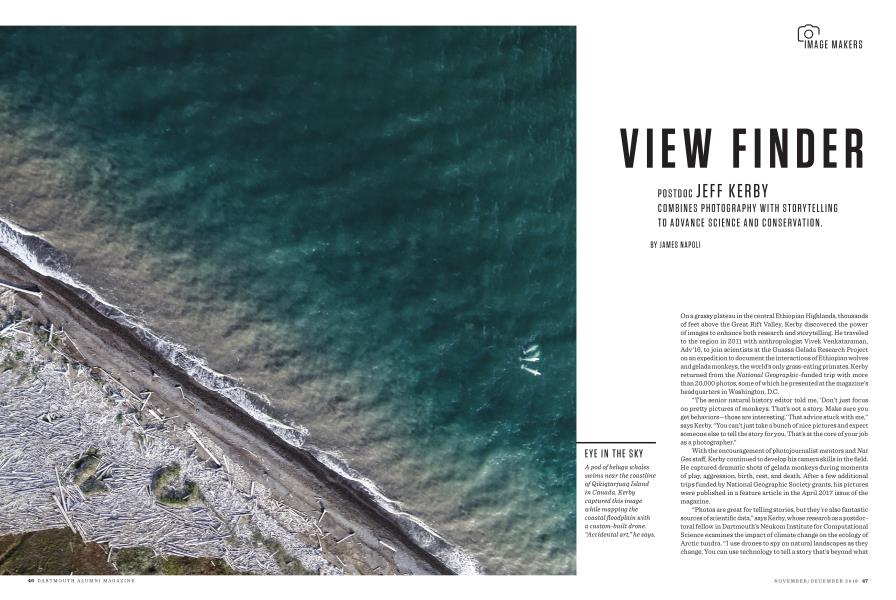

“Photos are great for telling stories, but they’re also fantastic sources of scientific data,” says Kerby, whose research as a postdoctoral fellow in Dartmouth’s Neukom Institute for Computational Science examines the impact of climate change on the ecology of Arctic tundra. “I use drones to spy on natural landscapes as they change. You can use technology to tell a story that’s beyond what humans can observe on their own, for example, by making a 3-D model that captures the thawing of permafrost over a huge area and several years.”

For the past three years Kerby has joined the environmental studies foreign studies program in southern Africa to assist undergraduates with landscape mapping and analyses using drone photography. Back in Hanover, students have pulled data from videos of robots in a BattleBot-esque arena as part of an exercise that explores animal behavior and landscape patterns in Kerby’s upper-level course, “Spatial Thinking in Ecology and Conservation.”

Recently Kerby cofounded the High-Latitude Drone Ecology Network, a group of researchers from across Eurasia and North America who share field expertise and develop protocols for landscape mapping in challenging northern environments. He’s optimistic about the potential of drone photography as a tool for science. “There’s a lot of opportunity to shift how we’re looking at climate change in the Arctic,” he says. “How can we revisit this challenge from a new perspective? Sometimes you have to bring new tools to old problems. That’s when the most powerful advances happen.”

You can view a slideshow of Kerby’s work here.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

YOUR TURN

YOUR TURNYOUR TURN

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 -

notebook

notebookMagic to Live By

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By ROB WOLFE ’12 -

Photography

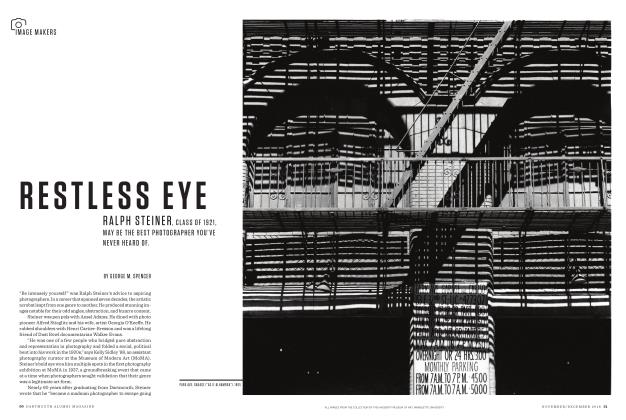

PhotographyRestless Eye

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBlood, Guts, and Beer

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By WILLIAM LAMB ’67 -

class notes

class notesDeaths

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 -

SPORTS

SPORTSThree-For-All

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By CHARLES MONAGAN ’72

Photography

-

BIG PICTURE

BIG PICTUREFairway to Heaven

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 -

Photography

PhotographyBIG PICTURE: At Work in the Murk

MAY | JUNE 2016 -

BIG PICTURE

BIG PICTURESitting Presidents

JULY | AUGUST 2016 -

Photography

PhotographyUnder Wraps

MARCH|APRIL 2019 -

Photography

PhotographyBig Green Apple

MARCH|APRIL 2019 -

Photography

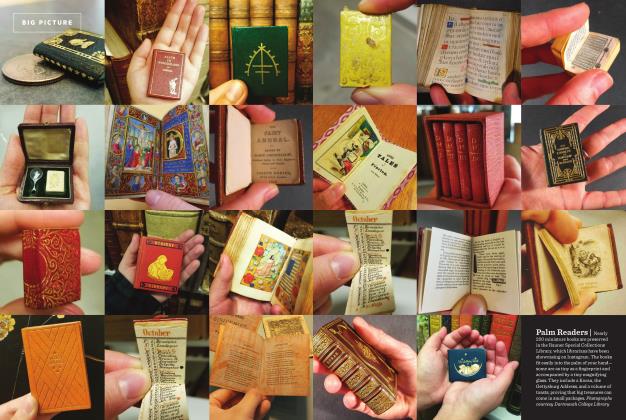

PhotographyPalm Readers

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019

Photography

-

Photography

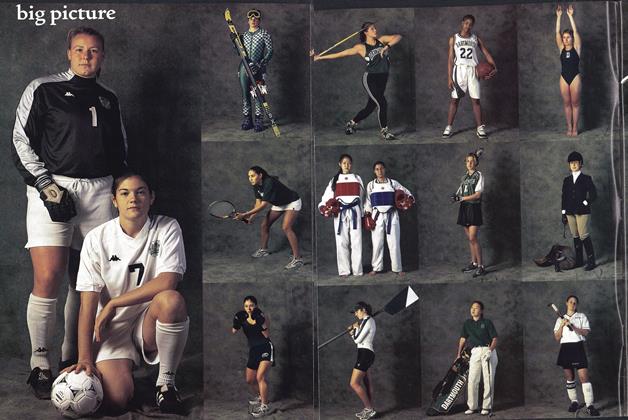

PhotographyBig Picture: In a League of Their Own

May/June 2001 -

Big Picture

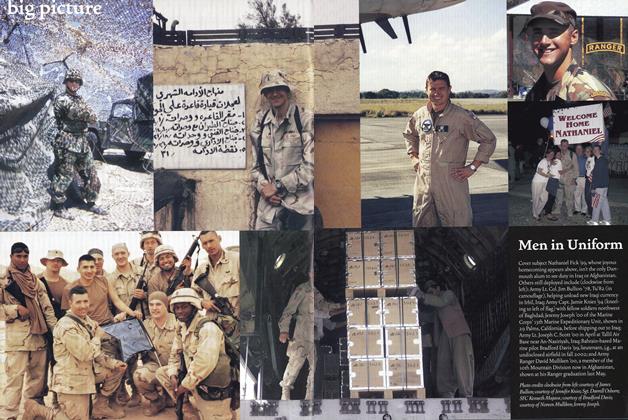

Big PictureMen in Uniform

Jan/Feb 2004 -

BIG PICTURE

BIG PICTURELife of the Mind

JULY | AUGUST 2023 -

Photography

PhotographyBig Picture: Even Keel

May/June 2013 By Bernie Roesler '12 -

Photography

PhotographyBig Picture: Changing Lanes

Sept/Oct 2009 By Joseph Mehling '69 -

Photography

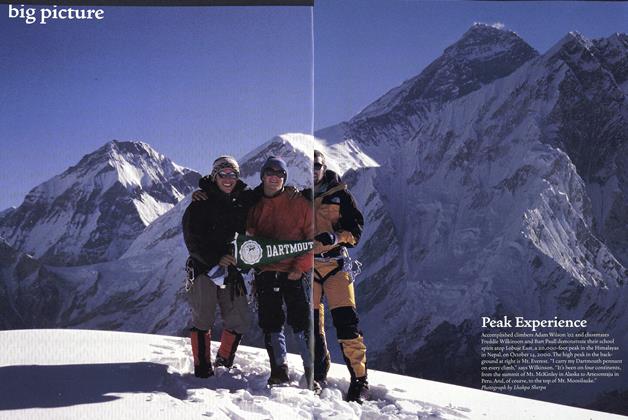

PhotographyBig Picture: Peak Experience

Mar/Apr 2002 By Lhakpa Sherpa