Power Players

Laura Stacey ’16 hopes for her second Olympic gold, following in the tradition of Dartmouth hockey legends.

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 CHRIS QUIRKLaura Stacey ’16 hopes for her second Olympic gold, following in the tradition of Dartmouth hockey legends.

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 CHRIS QUIRKWith 10:30 remaining in the second period of last year’s International Ice Hockey Federation Women’s World Championship in the Czech Republic, Team Canada’s Laura Stacey chased a loose puck her teammate had slung along the boards behind Team USA’s net.

It had been a pitched and at times ill-tempered match between the longtime rivals in a game that will be remembered as a classic. The Canadians were the reigning world champions, but behind 2-1, they were looking for an equalizer.

Two blue-shirted American defenders immediately descended on Stacey, who tied them up in an awkward tangle, leaving the puck unattended. Team Canada captain Marie-Philip Poulin then slipped in and sent a laser pass from behind the net to teammate Jennifer Gardiner for a tap-in goal. Game tied.

It was the kind of gritty, hard-nosed play that often goes unnoticed in the celebration after a goal is scored, but Stacey’s scrappiness is prized by teammates and coaches. And it’s a style that has defined Dartmouth’s women’s hockey program almost since its inception in 1978, six years after the College first admitted women. “The Dartmouth teams of old were just big, mean, tough, very intimidating, and very imposing,” says Maura Crowell, current coach of the Dartmouth women’s hockey team. “They were the belles of the ball.”

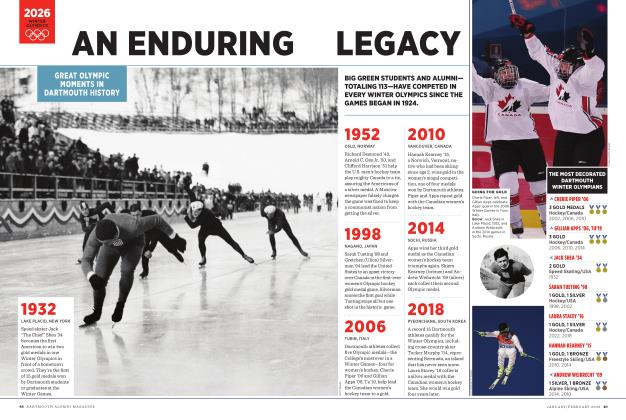

The United States won that world championship match, 4-3, on a last-gasp goal in overtime, but the two hockey heavyweights have been trading championships for more than three decades. In the 24 world championship tournaments held since 1990, Canada has won 13, the United States 11. Since women’s ice hockey became an Olympic sport in 1998, either the United States or Canada has won every gold medal—two for the Americans and five for Canada. And at least one Dartmouth player has played in every Olympic final, six times coming away with gold, either for the United States or Canada.

It’s a remarkable string of Olympic excellence by Dartmouth women. Of the 22 total Olympic gold medals won by Big Green athletes in all events, winter and summer, women’s hockey players have won 10, including Stacey’s gold for Canada in 2022. At the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan and Cortina, Italy, the United States and Canada are expected to meet in the final, when Stacey will have a shot at extending the Dartmouth legacy.

Americans Sarah Tueting ’98 and Gretchen (Ulion) Silverman ’94 played in the inaugural Olympic competition in 1998, at a time when Dartmouth ruled Ivy League hockey, winning the championship four times between 1991 and 1998. Silverman still holds the Dartmouth record for career goals with 189. Together with their teammates, the duo brought home gold medals for Team USA, upsetting the favored Canadian skaters, 3-1, in the final. Silverman scored the opening goal in that game and logged an assist, while Tueting had a stellar outing, stopping 21 of 22 shots on the night.

“Gretchen was truly a pure goal scorer, and she was so smart. She was on a different level when she was at Dartmouth,” says Judy Parish Oberting ’91, who took over as head coach at Dartmouth after the 1998 Olympics. “Sarah was remarkable when she was here. I don’t think anyone was surprised when they made the [national] team.”

There was something special happening in Hanover in those days. Parish Oberting, a star Big Green player herself, describes a bravado that emanated from the Dartmouth squad. “They were cocky, confident, proud. I loved to watch the team get off the bus with a little bit of strut,” she says. “You wanted the other team to feel like a freight train is coming upon them. Don’t give them a minute. We never want to let those defensemen face up ice. You want to get them right when they are retrieving the puck and make sure they feel that pressure, that force, that intimidation.”

Dartmouth quickly became a magnet for top hockey talent, aided by the extensive recruitment efforts of Parish Oberting and her assistant and later head coach Mark Hudak. “We made a concerted effort to recruit outside the region, so I spent quite a bit of time up in Canada,” Hudak says. “We were very fortunate and in the first couple years were able to recruit Cherie Piper [’06], Gillian Apps [’06, Tu’19], and Katie Weatherston [’06], who were all special players.” The trio became the backbone of the dominant Dartmouth teams of the early 2000s, winning the Eastern College Athletic Conference championship three times from 2000 to 2007. They also won gold medals at the Olympics with the Canadian national team.

The influx of talent created a pipeline for even more great players. “Once you have good players, the other good players want to come, and our players were phenomenal ambassadors,” says Parish Oberting. The wealth of talent, in turn, made Dartmouth a launchpad to the national teams in the United States and Canada. “You had an environment that people can step into and be playing competitively with some of the best players in the game.”

Though Stacey joined the team a decade after Piper and company, in a sense she was also an old-school Dartmouth player. A strong, tenacious winger who forechecks with malice but can also score goals and dish out assists, at the College she was captain of the team in her senior year and led the team in points with 10 goals and 13 assists.

But the last decade has not been kind to the Dartmouth program—the team has not had a winning record since the 2012-13 season—and the pipeline to Olympic competition has thinned. The only two Dartmouth Olympic hopefuls for 2026 are Stacey and current Big Green netminder Michaela Hesova ’28 for Czechia.

In recent years, more schools upped their recruiting and funding for women’s hockey, Hudak says. “The competition for talent went right through the roof.” But Parish Oberting sees green shoots with Coach Crowell now at the helm, and the team has won a couple of signature victories against top competition. “I certainly feel like it’s back, and Maura has done an amazing job,” she says. “In talking to her, you feel that same dedication to the player and the program in creating something that’s just not about her success but about understanding what Dartmouth is all about.”

Stacey has modeled her game on Apps, a three-time gold medalist and Dartmouth legend. “When I was a kid, I always looked up to her. She was a big, strong power forward, and that’s the type of player I always wanted to be,” Stacey says.

At 6 feet tall and 175 pounds, Apps somehow led the Big Green in both goals (30) and penalty minutes (281) as a senior. “The goals didn’t have to be pretty, and I took a lot of pride in playing in all areas of the ice,” Apps told Dartmouth Alumni Magazine in 2022. “I wasn’t afraid to sort of get into the corners and do some of the dirty work.”

Gillian Apps, a fixture on the Dartmouth squad from 2002 to 2007, won three Olympic gold medals. (Photo from Dartmouth Athletics)

Gillian Apps, a fixture on the Dartmouth squad from 2002 to 2007, won three Olympic gold medals. (Photo from Dartmouth Athletics)

Apps is now one of Stacey’s biggest fans. “She is my favorite person to watch,” Apps says. “I just had coffee with her in Toronto a couple weeks ago, and she’s one of those players that just gets better and better every year.”

Hudak says the Dartmouth warrior ethos that coaches cultivated early on really helped the team gel. Former coach George Crowe “started something awesome, and Judy built on that. I was fortunate to follow in their footsteps,” he says. “We were very intentional about building a championship culture, and we also talked about core values. I really tried to drive that home with the players, so they knew we cared about them as a person first.”

On the ice, the Dartmouth system was so successful that the coaching challenge was balancing some of the best talent in the game. Hudak explains that on an offensive line you typically look for one leader who can carry the line and two supporters. “It was tough having so many players who could be leaders. We had players who could carry a line, but they were playing with Cherie Piper, who was one of the best hockey players in the world at that time. I give them a lot of credit for recognizing what a great opportunity it was to play with teammates who were so good.”

Hudak recounts that they never had the players’ names on the backs of jerseys. A reporter once asked a player if it was something the coach wasn’t allowing them to do. “She said it has nothing to do with the coach. We play for the name on the front of the jersey,” Hudak says.

On the personal side, players felt supported on the ice and off, in their studies and in their lives. It was a holistic—and effective—approach to coaching that was not as prevalent two or three decades ago as it is now.

It made a difference to Stacey, who had to consider whether to stay in the sport after a devastating injury in 2016, in her final Dartmouth game, when she fractured both her wrists crashing into the boards. “I had amazing teammates, coaches, and training staff. I just saw my trainer from Dartmouth at a professional game in Boston, and I still remember the impact he had on me when I broke my wrists,” she says. “He showed up at the hospital with me, he was at the gym in the early mornings and at physio constantly, and he kept asking me, ‘Do you want that to be your last game?’ I didn’t want to give up just because of this severe injury, and he wouldn’t let me.”

It took almost a year, but Stacey recovered fully, made the national team, and won a silver medal at the 2018 Olympics. She returned with Team Canada in 2022 and won the gold. “It still gives me shivers talking about it because I was a little girl dreaming about standing on the blue line, winning the gold, and singing our Canadian national anthem.”

Now, Stacey is slated to skate for Team Canada for this year’s Olympics, perhaps her last. “I want to do whatever it takes to help that team win gold. But I think for me, it’s also staying in the present and enjoying every minute of this competition,” she says. “It’s really easy to look ahead, but I don’t want to miss anything along the way.”

Chris Quirk is a frequent DAM contributor who lives in New York and Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

2026 WINTER OLYMPICS

2026 WINTER OLYMPICSChasing Glory

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By PEGGY SHINN -

2026 WINTER OLYMPICS

2026 WINTER OLYMPICSOlympic Dreams

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 -

2026 WINTER OLYMPICS

2026 WINTER OLYMPICSAn Enduring Legacy

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 -

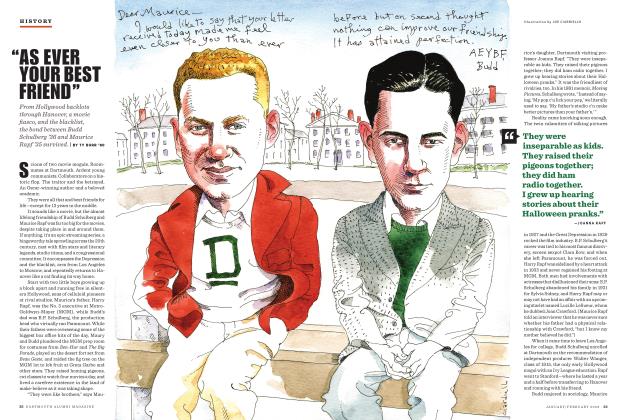

HISTORY

HISTORY“As Ever Your Best Friend”

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By TY BURR ’80 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEHer Lessons Echo Still

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2026 By DAVID DOWNIE '88

CHRIS QUIRK

-

PURSUITS

PURSUITSTo the Stars

JULY | AUGUST 2022 By Chris Quirk -

notebook

notebookHelping Those Who Help

JULY | AUGUST 2023 By CHRIS QUIRK -

PURSUITS

PURSUITSHockey Quant

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By Chris Quirk -

Features

FeaturesBeyond Words

MARCH | APRIL 2024 By CHRIS QUIRK -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Matchmakers

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Features

FeaturesIn the Face of Depression

MAY | JUNE 2025 By CHRIS QUIRK