THE PART WHICH OUR COLLEGES MUST HENCEFORTH BE EXPECTED TO TAKE IN THE TRAINING OF THE GENTLEMAN

OCTOBER 1905THE PART WHICH OUR COLLEGES MUST HENCEFORTH BE EXPECTED TO TAKE IN THE TRAINING OF THE GENTLEMAN OCTOBER 1905

PRESIDENT TUCKER'S ADDRESS AT THE OPENING OF COLLEGE

THE College is now open, Gentlemen, for the one hundred and thirty-sixth year of its work. On behalf of the Trustees, and Faculty, and on behalf of our wide fellowship of graduates, I welcome you, whether you are entering College, or returning to it. Every year of college life has its own charm and distinction. It is a great step from the environment of the School to that of the College, and every step which one takes in advance gives satisfaction and strength, provided one rightly measures the pace of the College.

I wish to speak to you, with as much brevity as the subject will allow, upon a somewhat unusual academic theme, namely, The Part which our Colleges must henceforth be expected to take in the Training of the Gentleman.

The presentation of this subject does not imply that our colleges have not heretofore trained gentlemen. That has been one of their assumed functions. . Neither does it imply that men do not enter college as gentlemen. In the reported act of courtesy on the part of the son of the President, it was generally claimed that the act was typical of the average American boy. It was put to the credit of the President's son that the common healthy instinct had not been perverted by his position.

I introduce this subject because of certain conditions which are beginning to manifest themselves within our colleges; which are making the training, or if you please, the practice of a gentleman, more difficult. Men who enter the colleges are seen to be of three types, when measured by their ruling ambitions or tastes. We still have men possessed of the high passion for scholarship, whether that passion be expressed in the older delights of culture, or in the newer joy of research. I should not like to believe that the mind of our American youth had ceased to respond at the very first chance, or continuously, to the great subject-matter of scholarship—the experiences and the aspirations of men as recorded in the literatures of the world, or their reasonings as stimulated by scientific discovery. My faith in the survival of the passion of scholarship in the midst of the intellectual temptations of modern life is sustained by facts. The scholar still lives in our colleges. He is here, he is everywhere, though his tribe is small.

Of course the prevailingtype of mind in the colleges is set towards affairs. It is well that it is so. If the exclusive, or chief product of the colleges was the scholar, we should soon cease to have scholarship. We should have in its place pedantry. It is the intellectual competition from the world of affairs which keeps the modern scholar alive. The proportion of the scholar to the pedant was never so high as it is to-day.

A third type of the college man, seen in increasing numbers, represents in one form or another the social aspects of college life. The large increase of this class is due to two causes: first, to the long prosperity of the country which not only enables many more families to send their sons to college, but also awakens in them corresponding social ambitions; and second, to the greatly increased attractiveness of college life itself. The college man of this type is not necessarily aimless, but he is not usually possessed of the tastes of the scholar, nor of the ambitions of the man of affairs. What he wants is college life, not college work. Now the organization of a part of college life around the idea of leisure rather than of work may seem to be helpful in the training of the gentleman. And so it is. The danger comes in, as I shall show you, when the right proportion in the allotment of time is violated, or when without any reference to time the whole interest in a man's thought and desire goes one way.

One condition then, which is comparatively new to American colleges, greatly affecting their office in the training of a gentleman, is the organization of leisure to the degree of very marked encroachment upon work. The other condition, also comparatively new, and affecting still more the work of training the gentleman, is the exposure of college life so completely to the methods and standards of the outer world set toward commercial success, a condition which needs no explanation until I come to apply it to our situation.

Let me now tell you with the utmost definiteness and frankness what I think that we must do to fulfill our part in the training of gentlemen. There are certain essentials in the making of a gentleman which underlie all the social conventionalities and give the reason for their existence. We must bear in mind that we have to do with men who are to declare the habit of their lives chiefly through their relation to the traditions and customs and social estimates of their own country. A gentleman is of course a gentleman the world around, but as Phillips Brooks once said, the cry of one nation to another is '' show us your man."

The first essential which must be insisted upon by the colleges in the training of the gentleman is efficiency, not because it is the finest thing, but because it is fundamental. The social order with which you will have to do and according; to which you will be estimated, is organized around work rather than around leisure. This distinction, however, may be more apparent than real. The social order in many of the older countries which is marked by the absence of those compelling callings, which we call work, has its own duties and responsibilities which allow very little of actual leisure. The boy of rank is born into a. well ordered life. The routine of the household, so far as it affects him, is exacting. And when he reaches the earliest approaches to maturity he is set at tasks, or placed in positions, which test him. An American family of fortune is more apt to produce untrained, if not uneducated, and irresponsible sons, than is an English family of rank. I take the liberty of reading an extract from a recent letter from Lord Dartmouth, which -gives without the slightest intention a glimpse into the responsible activities of a well trained English family. "It may be of interest to you to know," he says, writing under date of August 21, "that my youngest son is now a Middy on H. M. S. King Edward VII, which helped to entertain the French Fleet at Brest; that my second son is on the point of starting for Central Africa, under the auspices of the British Museum, on a tour of collection and exploration; and that the oldest is the accepted candidate on the tariff reform platform, at the next general election for West Bromwich. He has made an excellent start, though it is very doubtful if he will be returned. The opposition in the constituency claim to be absolutely certain that he won't, but at any rate he will put up a good fight."

This is the record of three sons of an English House in their present training for some form of public service. The oldest not much beyond his majority. That there are idlers and profligates among young men of rank is well understood, but they are very costly. The great Houses cannot long sustain themselves except through virile and well-trained sons.

The whole trend of the better American life is against inefficiency. The shirk can never be rated amongst us as a gentleman. The colleges therefore of this country are expected to see to it that the men whom they turn out year by year satisfy the national demand, the social as well as the business demand, for efficiency. The chief way of meeting this demand must be through the spirit which obtains in our colleges, in which all who are concerned must have a part. The administration of a college must be in itself efficient, the teaching must be stimulating as well as accurate, and the public sentiment of the college must be intolerant of the shirk. But the spirit of the college must be measured by its standards, and these in turn must be maintained in part by its rules. Rules are for those who are relatively indifferent to the spirit of a college—probably at any given time not more than one-fourth of its membership, but a very controlling part, if not held to the college standards.

In the enrollment for the present year it will appear that six men in the last Junior class fail to make Senior standing; that twenty men in the last Sophomore class fail to make Junior standing; and that twenty-one men in the last Freshman class fail to make Sophomore standing—fifty men in all who cannot be advanced to their natural place. There are in some cases entirely sufficient and honorable reasons why men who are due to enter a succeeding class should not enter it, but the above result shows a disregard of one element of efficiency, namely, the doing of one's work in time. To arrest this tendency, a new rule will go into operation the present year to this effect:

"The number of hours upon which the standing of a student for any semester shall be computed shall not be less than the minimum number of hours required for that semester."

Any student, that is, who sees fit to absent himself from a course which he thinks that he cannot make without too much effort will have his failure in that course charged to his account in his general average at the end of the semester. It will be seen that it is much better for one to have a partial failure, say of thirty or forty, reckoned into his average, than a total failure at zero, a rating which will affect particularly those who are on scholarships, or those whose general standing is insecure. I will also state that it is very doubtful if the Summer School will be open here- after to deficients, at least to those whose deficiences are due to absences from recitations.

These announcements are made in the interest of those who endanger their own efficiency, and the efficiency of the College, through their postponement of work. The order of the modern world in which you will soon take your places does not recognize the gentleman of leisure, if by that term is meant the man who shirks a present and common duty to gratify a present and personal mood. For a man to ask other men to wait upon his moods is more than a gentleman ought to ask. Respect for time is a necessary element in the training of the modern gentleman, because that involves in so large degree the element of consideration for others.

But efficiency does not make a gentleman. There are a great many efficient men who are very far from being gentlemen. Judged by this test there is no distinction between honorable and questionable successes. What may the efficient man lack among the essentials of a gentleman? He may lack honor. He has force, it may be in abundance. His power may be without quality. How shall we define honor. Let us turn to that master of the higher ethics — Wordsworth.

"Say what is honor ? 'Tis the finest sense Of justice which the human mind can frame, Intent each lurking frailty to disclaim, And guard the way of life from all offense suffered or done."

Or let us take the statement of those whose art is careful discrimination, who say of honor that "it is the nice sense of what is right, just, and true, with course of life corresponding thereto: a strict conformity to the duty imposed by conscience, by position, or by privilege."

Honor then as you see is made up largely of personal sensitiveness. Poet and lexicographer are agreed in calling it a sense. It indicates not so much what a man thinks about a thing, as how he feels about it in all his nature. It can be defined only in personal terms. You can fix the standard of honesty — above such a line a man is honest, below it he is dishonest. You cannot draw the line of generosity above which a man acts nobly, below which he is mean. Much less can you fix the standard of honor. It is in the man himself. Hence the training toward honor is a training first toward sensitiveness to what is just, right, and true, and then a training of the will to enforce this finer sense in action.

Let us apply this principle to college life. The supreme test of honor is no longer to be found in what is known as the "honor system." For various reasons the stress of temptation does not now fall upon honesty in examinations. The examination system has become really a part of the college curriculum. It has ceased, that is, to be an outside game between professor and student. Competition among scholars no longer leads one man to take unfair advantage of another. And college sentiment is steadily at work upon the individual student toward honesty. The increasing effect from class to class is very perceptible. By the time of graduation there is scarcely a man who would not scorn to cheat in examination. The penalty at this point, which is capital punishment, must remain till every vestige of dishonesty is removed, but there has been a steady and rapid decline in this form of college dishonor.

For the most practical tests of honor we must turn from college work to college sport. The law of temptation, gentlemen, is very simple. Temptation follows the life. Wherever the life centers, there temptation does its strongest work. Now college life is at present more intense, more congested, more subject to the irresponsibilities of excitement, on the field of sport than anywhere else. And this holds true not merely during the progress of a game, but at every point in those organized activities which represent competitive athletics. I do not propose to enumerate the various points in these organized activities at which college honor is liable to suffer, partly because I do not wish to give a disproportionate place to this phase of any subject, but chiefly because I believe that the organization of athletics has tended more and more to the purification of athletics. Through the persistent work of athletic committees, and of many captains and managers, and of many coaches, a great many dishonorable practices and methods have been organized out of the system. In fact so much has been accomplished through organization, and through the publicity attending organized methods, that it has now become possible to take the appeal in behalf of college honor in sport distinctly to two parties which have not heretofore been sufficiently in evidence. It has now become possible to appeal as never before to the second thought of the whole student body of a college, including some of the faculty. Heretofore, a college has virtually said to the athlete, "You win the game, we will do the rest." But the intelligent men of a college no longer stake their interest on the fortune of a game. They wait the verdict of the season, That verdict is the verdict of experts, which takes less and less account of mere victories and more and more account of those athletic values in men and in teams which represent honest training and honest work.

And it has now become possible to take the appeal more directly to the honor of the athlete himself. There is the place where in the last resort it must fall — upon his sense of honor. It is right to demand and to expect the growth of honor in the college athlete. You recall one of the more practical definitions of honor which I quoted — "conformity in conduct to one's position or privilege."

The college athlete has reached an exacting position or privilege, more exacting than he is probably aware of. He has become, in college sentiment and in that outside sentiment which a college controls, the representative college man. He has for the time being displaced the scholar, the debater, and all other traditional representatives. Such a position must be to him his own sufficient reward, else he will forfeit his right to it. The moment that a college athlete asks for other rewards than the high honor of his fellows, that moment he ceases to be worthy of their honor.

The whole argument against the denial of the right of the college athlete to outside earnings because of its assumed discrimination against poor men, has always seemed to me utterly irrelevant. Any man is at liberty to earn money through his athletic abilities. It is an entirely honorable way of earning money. But when a man becomes a college athlete he makes his choice between honor and money as his reward, and if he chooses honor, his own sense of honor ought to hold him to his choice.

I have been speaking of college life as reaching its greatest intensity in athletics. But side by side with this intensity, there is to be noted a diffusion of college life over many and various interests which exposes it to the ordinary temptations of the outer world. A college does so much business, that the men who carry it on are constantly exposed to what are falsely termed "business methods." They have the opportunity, and are often solicited to make private gain out of the occasions for rendering public service to organizations, classes, or the college. Personal initiative, enterprise, management have their proper rewards in college as elsewhere. There are services which ought to be paid for. It is not improper to seek openly positions which allow these services, provided one is competent to fill them. But in all such cases there should be the strictest regard to accurate and responsible expenditures of money. I urge upon every class the necessity of a careful record of all of it's business meetings. Make the class secretaryship the most responsible position in the class, both in college and afterwards. And in all organizations, which represent private enterprise, but which have to do with the college name or the college reputation, see to it that there is a clear rendering of accounts to all parties concerned. I deplore the slightest tendency on the part of college men to utilize public service for private gain. The most despicable word which has crept into current speech is the word "graft." Let it not be so much as named, because of the fact, in the college world. If a man's honor is not quick at this point, his college has everything to fear from him, and nothing to hope for in the future.

The efficient man, if he be possessed of honor, must be essentially a gentleman. Of that there can be no doubt. But I think that the term allows something more. Honor does not quite express that unselfishness of character and of action which we like to ascribe to a gentleman. I should add, therefore, to efficiency and honor, devotion, that outgoing and saving force which is needed to satisfy our conception of a gentleman in the full capacity of his life or in its most generous action. Honor is not a negative force; far from it. But it is largely a restraining force. It keeps one back from injustice, untruth, and wrongdoing toward others. And it may be a quick and mighty incentive to brave and generous action. But honor has never been quite a sufficient power, as we measure the great, saving powers of the world. It gave us the many gains of the age of chivalry, but it did not fight the battles of modern freedom, nor found the modern state or church. It gave us the crusader, but not the missionary. We somehow feel that we must have the man to-day, and surely he ought to be a gentleman, who can teach us how to rule our cities, how to control and guide our corporate wealth, how to rescue society from its hard and selfish weariness. And in so far as we have men of this type in society, in control of corporate power, ruling over cities, at the head of the nation, we feel that we have in them more than efficiency, more than honor. We are conscious of a devotion on their part, inspiringin itsunselfishness, which we should not wish to leave out of our ideal of manhood. Our gentleman cannot be an insufficient man, and selfishness is the great insufficiency.

I lave not dwelt, as you have noticed, in this talk about the part which the college may take in the training of a gentleman, upon forms or conventionalities. Every gentleman respects form. Respect for form can be taught or at least inculcated, but not form itself. One comes to be at ease in society by going into society. Manners come by observation. We imitate, we follow the better fashion of society, the better behavior of men. Good breeding consists first in the attention of others in our behalf to certain necessary details, then in our attention to them. We come in time to draw close and nice distinctions. This little thing is right, that is not quite right. So we grow into the formal habits of a gentleman. "Good manners are made up of constant and petty sacrifices." So says Emerson. It is well to keep this saying in mind as a qualification of another of his more familiar sayings:—"Give me a thought, and my hands and legs and voice and face will all go right. It is only when mind and character slumber that the dress can be seen."

I like to see the well-bred man, to whom the details of social life have become a second nature. I like also to see the play of that first healthy instinct in a true man which scorns a mean act, which will not allow him to take part in the making of a mean custom, which for example, if he be a college fellow, will not suffer him to treat another fellow as a fag. lam entirely sure that that man is a gentleman.

So then it is, in this world of books, of companionship, of sport, of struggle with some of us, of temptation also, and yet more of high incentives, we are all set to the task of coming out, and of helping one another to come out, as gentlemen. Do not miss, I beseech you, the greatness of the task. Do not miss its constancy. It is more than the incidental work of a college to train the efficient, the honorable, the unselfish man. A college-bred man must be able to show at all times and on all occasions the quality of his distinction.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

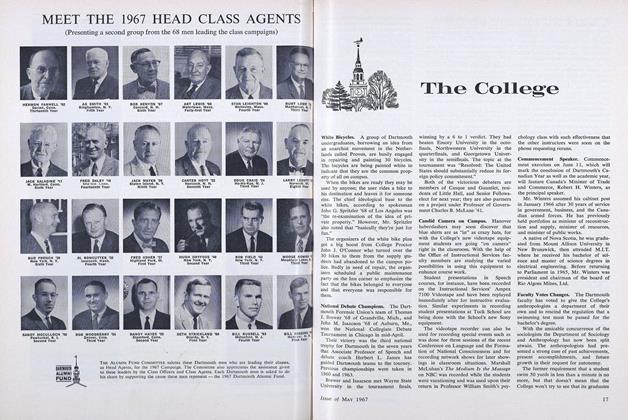

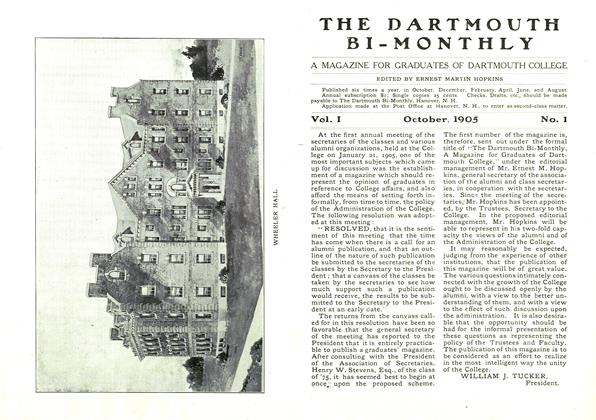

ArticleAt the first annual meeting of the secretaries

October 1905 By WILLIAM J. TUCKER -

Article

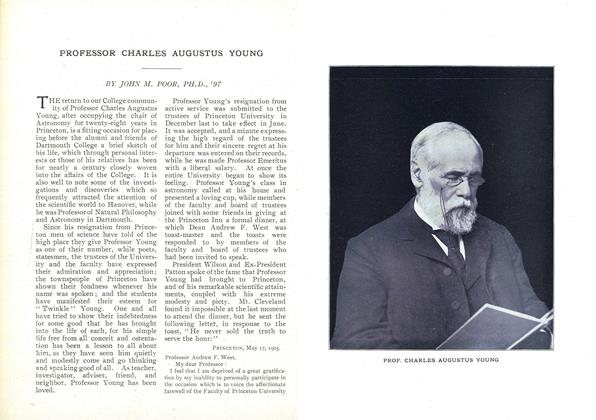

ArticlePROFESSOR CHARLES AUGUSTUS YOUNG

October 1905 By JOHN M. POOR, PH.D., '97 -

Article

ArticleJAPAN AND KOREA

October 1905 By K. ASAKAWA, PH.D., '99 -

Article

ArticleSANITATION AT DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

October 1905 By HOWARD NELSON KINGSFORD, M.D. '98 -

Class Notes

Class NotesNEW YORK ASSOCIATION AND THE DARTMOUTH CLUB OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK

October 1905 By Lucius E. Varney '99 -

Article

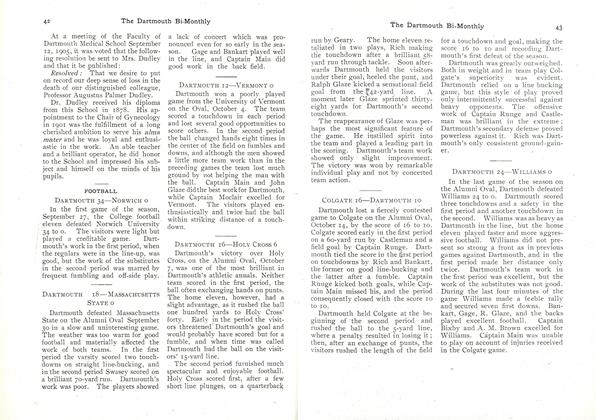

ArticleFOOTBALL

October 1905