IN the present relations of Korea with Japan we are witnessing the work of many forces rapidly shaping the destiny of a nation. The close connection between the two countries is, owing to their proximity to each other, as old as the authentic history of the Japanese Empire, but has acquired a new meaning since the latter entered into an active intercourse with the Powers. It is unnecessary to relate how Japan's new career made it imperative that Korea should not fall into the hands of any Power whose interest would be served by the maintenance of the exclusive policy and the corrupt administration of the peninsula. A compromise with such a Power has within the past decade been twice attempted by Japan, and has twice resulted in a disastrous war — with China in 1894-5, and with Russia in 1904-5. As soon as the last war broke out, however, Russia hastily withdrew herself from Seul, and Japan, now the sole master of the military situation in Korea, was enabled immediately to conclude with the latter, on February 23, 1904, a proctocol of alliance and reform. By this document, Japan guaranteed the independence and the territorial integrity of Korea, and the latter, in turn, promised to adopt Japan's advice and assistance regarding the reform of administration. In pursuance of this fundamental agreement, as it is described elsewhere,* several Japanese experts have been engaged as advisers in different departments of the peninsular government, and various works of reform have been accomplished with great rapidity. Among other things, the fisheries on the entire coast of Korea, as well as coast and river navigation, have teen thrown open; the Seul-Fusan Railway has been completed, and the Seul-Wyn and other railways are in construction; the currency, and the post, telegraphs, and telephones, have been improved and unified with the Japanese system ; and the local administration and foreign policy, also, indicate the . growing influence of the Japanese advisers over them. These and other changes are said to have already begun to alter the general aspect of the peninsula from one of indolence into that of intense and increasing activity. For weal or woe, Korea has been forced out of her wonted seclusion, and has at last begun the career of a modern State. Such a beginning was impossible but with the vigorous advice of Japan, and the latter, again, became binding only under the irresistible influence of her successful warfare.

The question arises if the more commanding position which Japan holds to-day in Korea than she did in February, 1904, has in any way neutralized the provisions of the protocol of that date. Of the two main principles of the protocol — namely, Korea's independence, and Japan's preponderating influence over Korea, has the latter advanced at the expense of the former so far as to have reduced it into a mere fiction? In the treaty of Portsmouth, Russia recognizes Japan's position in Korea, while little is said of the latter's independence. In the new Anglo-Japanese treaty of alliance, as well as in the accompanying dispatch by Lord Lansdowne to the British Ambassador at St. Petersburg, the principle of the open door in Korea is emphatically declared, but Japan's eventual control and tutelage of Korea are openly recognized. Technically speaking, however, Korea still is, as she was at the beginning of the war, a sovereign State, and Japan discharges administrative details only as they have been entrusted to her care and only in Korea's name. It would be extremely crude to speak as if Korea had become a province of the Japanese Empire. The practical question must be, whether, under Japan's protection, Korea is losing her independence or, on,the contrary, is learning the arts of self-government las a modern State.

One would think that historic examples tend to prove that the protectorate system offers not a few temptations, opportunities, and pretexts for an eventual absorption of the protected State by the protecting, or else it might result in a separation through a successful revolt of the protected party. Unless the Government of Japan possesses an unparalleled restraining power over the many forces which the war has set loose, it will, in spite of itself, be unmistakably and forcibly drawn toward the expected result. What, then, are these impelling forces, and what is the attitude of the Japanese Government toward them? No official document answers such a question, nor does any real occurrence constitute a decisive evidence. We must content ourselves by analyzing some of the points involved in the problem and regarding the position of Japan in the light of these points.

All will admit that Korea's independence and Japan's safety had been in constant danger so long as the administration of the former remained too corrupt and feeble to resist foreign pressure. Reform was a necessity. Few will deny that experience had taught Japan that no substantial reform could ensue if Korea were left alone to herself or placed under a joint counsel of two Powers, one of which found a source of its influence over Korea in the very corruption of her politics. Reform by the sole advice of Japan being imperative and having been rendered' possible, and protection having been justified by the course of events and by an agreement, the fundamental question arises as to which is the ultimate object of the reformatory and protective measures, — a thorough training of the Koreans for a complete self-government, or an assumption by Japan of one sovereign function after another of the Korean State, so that the protective regime would be indefinitely prolonged and finally pass into absorption ? Or, perhaps, does Japan leave this main issue undecided and to be moulded by the development of future events? It is true that the Japanese envoys at Portsmouth objected even to having the term protectorate applied to Japan's relation to Korea, but insisted on defining the relation as one of "paramount interest." On the other hand, no public pledge has been made by Japan that her tutelage over the peninsula would be ended at any future time. Nor is the policy, if any, of the present Cabinet of Tokio on this point certain to be resumed by the succeeding Cabinets. The parties and politicians of Tokio, some of whom may even come to control the affairs of State, may entertain various views on this subject, and a final annexation of Korea is perhaps desired by the majority.

Those who urge the last view maintain that it is beyond human possibility to train the Koreans for self-government. If it is pointed out that they have manifested an eager desire for independence and resented foreign control, the annexationists will reply that the idea of independence as held by these Koreans is hardly accompanied by any clear conception of the rights and duties of the modern State. An ignorant desire for self-government might well prove hazardous to the true independence of Korea. It is indeed most discouraging for "her friends to see that her long historic habit to eke out her existence between powerful neighbors by either propitiating them by flattery, or setting them against one another by intrigue, has bred in her politicians many of the minor traits of the suspicious servant. Many of them are noted as past masters of dissimulation and time-serving, but seldom evince independent conviction or disinterested patriotism. They are found perpetually distrusting and undoing one another, and applying the same method to -foreign Powers. If the petty acts of hypocrisy and faithlessness of some of the Seul politicians were published, the whole world would be amazed. Their feeling against Japan as an uncompromising reformer is intensified by the latter's occasional lapses into harshness, and also by the implacable hatred of the Korean Emperor of the nation who produced parties responsible for the murder of his late beloved queen. In spite of His Majesty's frequent expressions of good-will to Japan and of love of reform, the politics of Seul still continues in a chaotic state. So late as last August, the Premier and other Ministers of the Korean Cabinet utterly suspended their official duties, while its exiled member, Yi Yong-ik, was engaged with the former Russian Minister Pavloff, who is still in Shanghai, in an endeavor to reinstate Russian influence in the peninsula. A slight relax of oversight on the part of Japan might at any moment bringback the days of the underhanded diplomatic rivalry between Russia and Japan in Korea. If Korea possessed a handful of forceful, farsighted and, above all, disinterested statesmen, the question of her future would be simpler. The actual political stagnation of Seul is a great deterrent to a wholesome progress of national life, as well as a welcome pretext for the Japanese annexationists.

Having stated our fundamental question regarding Japan's policy in Korea, we may pass to another question closely connected with and hardly less important than the first. Which of the following alternative principles constitutes the primary motive of the policy, — to clear the ground for the progress and prosperity of the poor people of Korea, or rather to institute such measures of reform as are calculated at once to insure Japan's own prestige in Korea and to put herself in a favorable light before the world? The two principles may largely coincide in practice, but it might cause a great divergence in policy according as to which animates the conduct of the reformers. For example, the improvements which are already under way in transportation, communication, and currency, must greatly benefit the Korean peasant, as well as enormously strengthen Japan's position in Korea and before the trading world, both of which will derive therefrom many advantages hitherto unknown. So long, however, as the local administration remains unreformed, education neglected, and society barren and unstimulating, the peasant can hardly afford to bestir himself to take advantage of the new improvements which have been so abruptly thrust upon him. In more ways than one, the foreigner might rise m power while the Korean remains stationary, but keenly suffers from comparison. It is true that the centuries of oppression have so profoundly modified the character of the peasant that he presents an appearance of moral indifference, but to say that he is incorrigible is to unduly distrust human nature. An active diffusion of education, together with a thorough eradication of the venality and habitual extortion of the officials, assisted by the stimulus of the new surroundings, would at least create a situation in which the native capacity of the Koreans for progress may fairly be tested. If the policy of Japan is not pure exploitation but development, it may be reasonably expected that, now that the war has ended, her reformers will devote their energy to this most delicate task of reform of local administration and popular education. In this work they may derive many valuable lessons from the experience of Lord Cromer in Egypt.

If the Japanese Government is bent on such an enlightened policy toward the Koreans, it might encounter the most formidable difficulty in the Japanese colonists themselves. The latter might prove as prejudicial to the cause of popular improvement as the Seul politicians are to that of gradual training for self-government. The reports of the harsh treatment of the Koreans by the immigrants are happily becoming much less frequent than before, but it is problematical whether the majority of the sixty thousand Japanese in Korea and yet many others who will follow their steps have in view the community of interest of the two nations and pursue their enterprise accordingly. Many of them may have little regard even to the 'permanent interest of their fatherland, still less to the progress of the Koreans. Not a few will maintain that the natives are irremediably low and that it would be to no purpose to remove official corruption, which harries the natives but little affects the immigrants. They will not have many scruples in purchasing cultivated areas for a nominal sum and reducing the former owners into virtual serfdom, instead of breaking a new soil and adding to the resources already developed. Their high-handed acts might, like an accumulated force of fate, steadily impel the Japanese Government to advocate their vested interests and mould its policy according to them. Then its original intentions would be completely defeated, and the millions of the native peasants would perpetuate an unquenchable hatred of the intruder who had brought upon them miseries which were not of their own making but which redounded to his lucre. Such an eventuality may perhaps never materialize, but may be averted only by the greatest self-control of the colonist and restraint by his Government. It would be unwise to allow the lowest classes of Japanese laborers to migrate to Korea, for the wages are there lower than in Japan, and the Korean labor is abundant and good. The most welcome will be such professional people as doctors and teachers, of whom there is a dearth in the peninsula, and also responsible foresters, fishermen, and agriculturists with a fair amount of capital to be invested in their respective callings. It is encouraging to note that these desirable classes of colonists are rapidly growing in number. They may even prove to be a solid, resisting power against irresponsible adventurers who have largely preceded them. The latter, however, still greatly preponderate over the former both in number and influence. If the government does not control the colonists, it will be controlled by them.

From the foregoing discussion it would appear that, even if we assume that the policy of the present Japanese rulers aims at the development of the common interest of the two nations and the ultimate self-government of Korea, there are powerful forces at work in another direction. Necessity forbids that Japan should relinquish her protection over her neighbor at this stage, but the protection is attended, among other deterrent influences, by the lamentable state of the domestic politics in Korea and by the selfish greed of the Japanese settlers. Under these circumstances, an ultimate annexation would appear a more natural outcome than an eventual selfgovernment, for the latter would result only from such a perfect self-control and such a consummate tact or the part of the Japanese Government and colonists as are entirely unparalleled in human history. It is unjust to compare Japan's position m Korea with that of the United States in the Philippines or even in Cuba, for the United States and these islands do not economically depend on each other as do Japan and Korea, nor are there great warlike powers threatening the United States across these islands. Nor is Japan a federal republic the constitutional unity of which must be maintained against an unnecessary addition of permanent dependencies. Yet one may argue powerfully for the cause of anti-imperialism in Korea. He could wish that the Japanese Government would soon pledge and afterwards persistently prove that its temporary protection of Korea is calculated for her ultimate self-government, and that its policy aims at the advancement of the great common interest of the Korean and Japanese people. A departure from this position in favor of annexation cannot, even from the standpoint of mere policy, be said to be advantageous to Japan in the long run. Let The anti-imperialist plead his case.

"It is too late," writes a Japanese friend in Korea, an ardent wisher of the welfare of the Korean people, "to discuss whether or not Korea would be absorbed by Japan. The question is, at what time and under what title Japan may incorporate Korea under circumstances perfectly justifiable in the eye of the world. Time will come when Japan's general open policy in the Far East will have ingratiated her with other Powers to such an extent that the latter will condone her free action in Korea. The problem for the practical statesman now is how, after the absorption of the Korean State, its people may best be assimilated with the Japanese, given rights equal to those of the latter, and grow together in prosperity and happiness. The result of my educational work here during the past seven years inspires me with some hopes in this regard." Would the Powers condone Japan's violation of her own agreement with Korea concluded on February 23, 1904? It is true that the protectorate system is generally considered a necessity, and that even an absorption will be for the most part acquiesced in by the Powers as inevitable. Even M. Witte is said to have asked the Japanese peace envoy at Portsmouth to declare this policy in the latter's proposed terms for peace, and had Baron Komura done so, the Russian plenipotentiary would have agreed to the clause. The anti-imperialist will, however, say that the tacit consent of the world to the annexation of Korea must imply an-unexpressed malice or sarcasm of Japan's breach of faith. She will gain in power in Korea at the expense of the sympathy of the world. The intelligent section of Europe and America showed its good-will toward Japan during the war mainly because she resisted the faithless aggrandisement of Russia upon the territories of her independent neighbors, and antagonized her exclusive trade policy ; in other words, because the world expected that, if Japan won, her diplomacy would be upright, the East Asiatic nations would be independent and progressive, and the great economic division of the Orient would be opened to the world's trade and industry. If, after her triumph, Japan ignored her own agreement and absorbed Korea against her will, what would there be to choose between the Russia before the war and the Japan after it, but in the latter's open door policy ? Even here the voice is already raised saying that Japan stands for this policy merely because she can afford it on account of her cheap labor and near position, in the same way that Russia was obliged to adhere to an exclusive policy because she, at so great a distance from the Eastern markets, could not afford an open door. Even if the world may acquiesce in Japan's annexation of Korea, therefore, the open sympathy with which it has greeted her might gradually pass into a secret jealousy and cynicism, and her mundane advantage would be offset by a serious loss of moral prestige.

This state of things cannot, furthermore, help having a profound effect on the spiritual life of the Japanese nation. As soon as the nation becomes conscious that its greatness has been gained at the expense of another nation and by a questionable means, its failing conscience must be propped by a hardened moral sense. Its patriotism will lose in purity, and its dictates will begin to be secretly or openly doubted by some citizens. The loyalty of the people to the country's cause will no longer be so clear and whole-hearted as it has been, and Japan might thus lose'this great distinguishing mark of her life, and fall to the level of many a European State whose history contains pages of treason and anarchism.

Whether or not such a situation as the anti-imperialist apprehends will develop must largely depend, not only on the attitude of the Government and the colonists, but also on the general feeling of the Japanese nation. That, in spite of its remarkable catholicity of temper, the nation has been flushed by its unexpected victory over the great enemy can hardly be denied. A large section of the people seems to have dreamed of a complete exclusion of formidable rivals from the East and an economic and political expansion of Japan on a colossal scale in Korea and China. They would have expended a large portion of an indemnity from Russia, had they secured it, for a gigantic military .expansion and an unnatural subvention of industries. Were there no restraining power, they might readily plunge into an immoderate policy for the future, and would spare naught in order to insure the greatness of the Empire, as they erroneously thought, for all time. Precisely at this crucial point of its career, the Japanese nation was abruptly and forcibly reminded, by the conduct of the Privy Councillors regarding the terms of peace, of the distinction between the broad and open principles for which the war had been entered upon and the unimportant gains utterly foreign to those principles and liable to create a dangerous situation for the future. Moderation was thus forced upon the people, who must accept it and taste its bitter significance. After a stormy struggle with themselves, they will see that their dreams of immoderate expansion have been rudely shaken off. Thoughtless chauvinism has been generally and effectively checked. It will be extremely interesting to observe whether the new attitude toward the future which has so precipitately been thrust upon the national mind will have any material effect upon the evolution of the' Korean question.

*By the present writer in the AtlanticMonthly for November 1905.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAt the first annual meeting of the secretaries

October 1905 By WILLIAM J. TUCKER -

Article

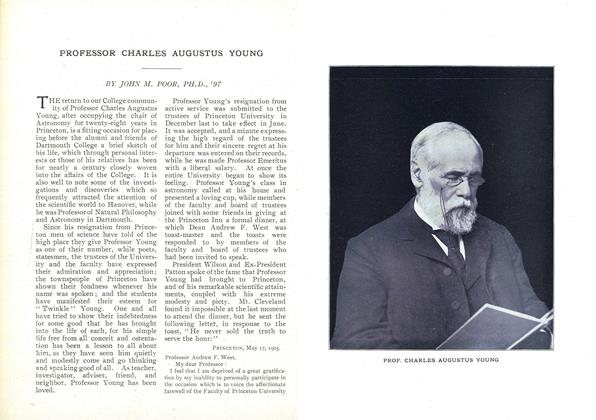

ArticlePROFESSOR CHARLES AUGUSTUS YOUNG

October 1905 By JOHN M. POOR, PH.D., '97 -

Article

ArticleTHE PART WHICH OUR COLLEGES MUST HENCEFORTH BE EXPECTED TO TAKE IN THE TRAINING OF THE GENTLEMAN

October 1905 -

Article

ArticleSANITATION AT DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

October 1905 By HOWARD NELSON KINGSFORD, M.D. '98 -

Class Notes

Class NotesNEW YORK ASSOCIATION AND THE DARTMOUTH CLUB OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK

October 1905 By Lucius E. Varney '99 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

October 1905