President Tucker's Address at the Opening of College

ON behalf of the Trustees and Faculty I greet you, Gentlemen, as with your coming you continue the work of the College into the one hundred and thirty-seventh year of its organized activities. I like to remind myself, and remind you, of our place in this historic and vital succession. We are here partly because of the unbroken line of graduates from 1770 to 1906. Much of the charm, the fascination, which belongs to the youth of persons, belongs to the age of institutions. The early names and the early events freshen with time. There are Dartmouth men among the dead as familiar to us and quite as influential in the shaping of our careers as any among the living. We feel the living in the mass. Among the dead they dwell apart.

The oldest graduate among the living belongs to the decade of the thirties in the last century. There are seven besides him in that decade. In the decade following, that of the forties, sixty-five are living.

In the fifties 217 In the sixties 343 In the seventies 599 In the eighties 621 In the nineties 761 In the six years of the present decade 815

To this body of workers distributed through the decades you join yourselves as undergraduates, a thousand strong. What is of infinitely more account you are a part of a great academic comradeship, represented by scores of colleges and universities throughout the country, each with its own inspiring history, each set to its local task, each committed to the well being of the Republic. You have, or will have, the spirit of this College. It will be one of the stimulating and restraining influences in your lives. Never for a moment allow yourselves to be so narrowed by it that you may not beat home anywhere in the great commonwealth of letters, or in the greater commonwealth of truth.

As we came together last year I discussed the social aspect of college life, emphasizing the part which our colleges and universities are expected to take in the training of the gentleman. Running through all routine and technical work of an academic sort there are three clear purposes which issue in personal results, the outcome of which can be expressed only in personal terms. The college man must be imbued with the spirit of the gentleman, he must be imbued with the spirit of scholarship, and he must be imbued with the spirit of citizenship. The claim of manners to a commanding place in the college world is as old as any academic foundation. The claim of citizenship is more modern but it is steadily growing clearer and more exacting. The claim of scholarship inheres in the original and abiding intention of the college. Not that our colleges may be expected to produce scholars in the same proportion and to the same degree in which they may be expected to produce gentlemen and citizens, but certainly it is a reasonable expectation that every college man is capable of being imbued to a certian extent with the spirit of scholarship. Otherwise a man is out of place in college. It is no advantage, as it is no credit to him, to be there.

I ask, therefore—it is the point of departure for my address,—Are the colleges of today sufficiently honoring the claims of scholarship? I ask this question as applicable equally to faculties and students.

It is applicable to faculties because we usually get from our students what we persistently ask for, provide for, and expect. The administrative policies which characterize the modern college are apparently contradictory in their effect upon scholarship. On the one hand the college has been opened to competing objects of ambition. Other standards of excellence than those determined by scholarship have been freely introduced and acknowledged. A generation ago a student could hardly satisfy his ambition except through rank in his class. Today he finds satisfaction in excellence in athletics, or through the acquirement of leadership in some one of the various activities of college life. The principle of competition is at work more effectively without the classroom than within.

On the other hand the adoption of the elective system has been a stimulus to individual scholarship. It has made study more interesting. It has enabled a great many men to find themselves. It has introduced the element of individuality into college work.

The modern college, then, is at a disadvantage in the matter of scholarship, when compared with its predecessor, in the fact that the principle of competition has been allowed to take effect elsewhere than in scholarship: it has the advantage over its predecessor, in the matter of scholarship, in the fact that it places before students for personal choice a wider, more varied, and more interesting curriculum.

Just how these two tendencies balance in any given case it is impossible to say, but I think that a third tendency has come in, quite unnoticed, which operates against scholarship in our colleges, namely, the tendency to allow the absorption of the idea of scholarship by the graduate school.

The result has been that the idea of work has been substituted for that of scholarship in our colleges. Scholarship, meaning thereby the idea of genuine, interested, protracted study, has been postponed to the .professional school. The scholar has become in our thinking a professional, just as much as a lawyer or a physician. We have ceased to expect scholarship until the circumstance allows the professionalized student, and have accepted in place of scholarship various gradations of work. I think that our colleges are suffering today from the want of respect, on the part of faculties, for amateur scholarship. I have referred to the gradations of work. The ranking system with us, as you know, divides men into classes according to the decimals between 50 and 100: A 90—100, B 80—90, C 70 —80, D 60—70, E 50—60.

This comparatively wide range of marking has been adopted because, in the language of one of the older members of the faculty, fifty points is none too much to express the difference between the maximum and minimum working of minds, the lowest of which is entitled to college recognition. But I have often thought that the formal result of this system is to increase the number on the lower ranges and to diminish the number on the higher range. This is on the assumption that marking is relative rather than absolute.

However this may be, about 54 per cent of the College during the first semester of last year was on the three upper grades and 46 per cent on the two lower grades,—though 16 per cent only was on the lowest grade. Classes vary in scholarship, but the rule is that scholarship, as judged by .the ranking systems, advances rapidly in Junior and Senior years. Thus in the record of the last year referred to 12 per cent of the Senior class ranked A, 22 per cent B, 35 per cent C, 21 per cent' D, and 10 per cent E.

It is evident that only the lowest grade represents what may be termed enforced scholarship. It is this grade which is the chief concern, so far as discipline is a matter of scholarship, of the committee on administration. Above this grade everything depends upon the spirit of scholarship. And for the development of this spirit a faculty has three means of influence: first, the proper adjustment of college activities, including college sports, to college work: second, the arrangement of the curriculum and of individual courses with the view to the greatest intellectual stimulus; and third, personal inspiration, of which the chief factor at present consists, as I believe, in the belief and expectation that the scholar can live and grow in the. atmosphere of the college. The spirit of scholarship is not precisely the spirit of celibacy, though the scholar committed to a given task may work to best advantage in the detached life of the graduate school.

Turning now to the attitude of undergraduate students to the question before us, we naturally find a corresponding disposition to restrict the sphere of scholarship. The scholar, according to college sentiment, may be the man of brilliant parts, the man distinctly of mind, but he is for the most part reckoned as the unsocial man, the man most out of sympathy with the temper of college life and activities. Of the actual men whom you may designate as scholars I can have nothing to say, but in what I may further say to you I want to try to change your interpretation of the spirit of scholarship. For, if it is rightly understood, I believe that all college men will have the sense to appreciate it at its true value, and that many who are now indifferent to its claims will have the sense to avail themselves of its incentives.

The greatest thing which can be said, and which is always to be said, about the spirit of scholarship is that it inculcates and developes the love of truth. This is peculiarly the significance of modern scholarship. The scholarship of today is not measured by the amount of one's learning but by the truthfulness of his knowledge. We are living under the aphorism of one of our late humorists —"It is better not to know so much, than to know so many things that are not so.” The first process in scholarship is to divest accredited knowledge of all assumptions, and uncertainties, and unrealities of any kind. So that if the process stops at this point it has created in the scholar a habit of mind of immense value. If you enter any of the professions with this habit of mind, law, medicine, teaching, the ministry, or any one of the great businesses, you cannot allow any sham, or sophistry, or other kinds of untruth, without a sharp mental protest. You tolerate any of these things at a mental cost which the untrained mind does not have to pay. This is the negative work of the spirit of scholarship. On the positive side it opens new fields of vision, a vast territory of thought and of action otherwise inaccessible. The truth loving mind is more apt to be endowed with insight, invention, initiative, than any other kind of mind. When once it enters upon its stimulating and exhilarating action it reacts upon the whole nature. I have seen men in College over and over again caught by the spirit of investigation in one of the natural or physical sciences, and thereby diverted if not converted from wasteful and demoralizing habits already formed. And as I have followed these particular men into their after work in no case have I seen a moral relapse. The spirit of scholarship is in its highest intent the spirit of and therefore shares in degree the great prerogative of truth— "The truth shall make you free."

It is not so much to say, but it is a great deal to say, that the spirit of scholarship is largely concerned with the training for power. The powerful men of today are of two types, men of will, and men of trained minds. Neither type is complete in itself. Will power unrelieved, or in excess, gives the overreaching or otherwise blundering man. Mental power unsupported often lacks initiative or endurance. But the trained mind represents, on the whole, better than any other one thing the present standard of power. It is, after all, the scholar in the broad sense of the term, the man who has learned how to investigate, to analyze, to reason, to invent, to anticipate, who is most in demand in the business world. A good address, activity, industry will carry a man pretty well along on the road to success, but if these be all, there comes a place at which he stops, and men of the training I have described go by him. I am not saying that some very indifferent scholars in college may not become successful in business or in the professions. What I am saying is that if they are genuinely successful, it is usually through having afterwards learned to use their minds in practically the same way in which they might have learned to use them while in college. The tasks are different, the problems are different, but the kind of mind called for is the same. Success of the highest sort in business means scholarship in business. There are no substitutes for it. The man who shirks it simply condemns himself to those grades where men are striving together in that kind of physical activity which the street calls "hustling."

I carry my thought a little further, and still more into the region of personal results, when I say to you that the spirit of scholarship is becoming more and more necessary for teaching men how to gratify their tastes properly through the use of money. If there is any class of students who for personal reasons ought to acquire the spirit of scholarship it is those who propose to make money. You who propose to do this, if you succeed, will be met after a little by the question,—How will you spend it? The question does not now seem to you to be of very serious account. It may prove to be the most serious question of a personal sort which you will have to answer. The most lamentable sight now before us is that of the great multitude of persons of easy wealth, who do not care to use their money for others, and who do not know how to spend it rationally on themselves. Most of the money which is now being spent in personal ways goes for show or for amusement. The spectacle has ceased to be attractive. I think that the stronger and clearer minded young men of the country are beginning to turn away from it. But if you had the money of these persons whom you no longer envy, and their tastes, what would you, or what could you, better do with the money? Do you not see that the question is really a question of desires and tastes? Do you not see how helpless a man is who is rich in money, but poor in imagination and taste?

To the man, therefore, who proposes to make money, for that for one reason or another is the motive underlying the transition from the old professions to business, the question as to how he shall spend so much of it as he can rightly spend upon himself or his family is of supreme importance. It must be anticipated. It cannot be satisfactorily answered by the mental powers and habits which have been used in the making of money. The right, or fit, or enjoyable spending of money calls for entirely different qualities from those required for gaining it. The college man who has trained himself to become a great earning force, but who has not trained those powers which at the proper time will teach him how to spend his earnings, is simply preparing himself for the fate of those whom he now sees and pities.

I enjoin most earnestly upon all of you who propose for yourselves a business career that you acquire now and at any cost the spirit of scholarship, for two reasons—first, because your time for study is limited when compared with the time of those who go over into professional studies, and secondly, because you will have in all probability the means of gratifying those tastes which the spirit of scholarship can create. Some of you will have access to the world of beauty in nature and in art. Some of you will be able to possess, not merely to own, but to possess the things which men value according to their intelligence and taste. Some of you will have the opportunity to use wealth for personal culture as well as for personal enjoyment.

Will you ignore these opportunities because you are not prepared to take them, and therefore give your time, your money, yourselves, to restless activities or cheap amusement? Or will you take these opportunities because you have prepared yourselves to take them through the training of your finer senses? The question, as it now confronts you, is really a question of scholarship. The spirit of scholarship becomes, when so directed, the spirit of the finer sensibilities and tastes. It is the spirit of discrimination. It teaches the difference between the coarse and the fine, just as it teaches the difference between the true and the false.

I do not claim that the spirit of scholarship is the deepest thing which appeals to our better nature—there is a stronger and a deeper call which leads us straight to service and to sacrifice. Of that I can speak more fitly at other times. Today I set forth the claims of the spirit of scholarship and its appeal to you. I want to make the perspective of college life clear to you, to some of you at the start, to some of you who have not yet really found it, or are not yet ordering your lives according to it. Do not mistake the incidents of college life for the substance of it. The incidents are full of color. They show for more than the plain substance. But not one, nor all of them would have given us this college—nor any college. Colleges are established and endowed and administered to give to each incoming generation access to the mind of the world. Incidentally they stand for free and generous companionship, for healthful activities, for honorable sport. But the end of it all, near at hand and far beyond, is the knowledge and valuation of those things which have made out of this world "the habitable earth," the fitting home for the sons of men. What are these things? Truth, and again truth, and power, and beauty. In these things, and in the still deeper joy of service and sacrifice, lies the desirable and attainable good of the world. Do not let the pleasures of the way detain you too much, nor divert you too far, so that you fail to reach the acknowledged and chosen end for which you have set your feet in this ancient pathway.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

October 1906 -

Article

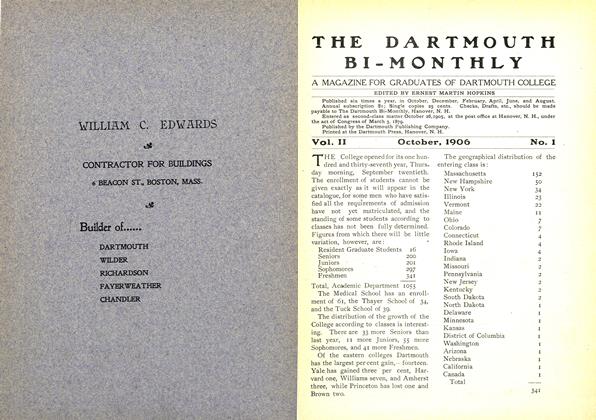

ArticleTHE College opened for its one hundred and thirty-seventh year,

October 1906 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH NIGHT DARTMOUTH NIGHT

October 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE ECONOMIC CONDITIONS OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

October 1906 By Warren M. Persons -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

October 1906 -

Article

ArticleCHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION

October 1906

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY NOTES

November 1918 -

Article

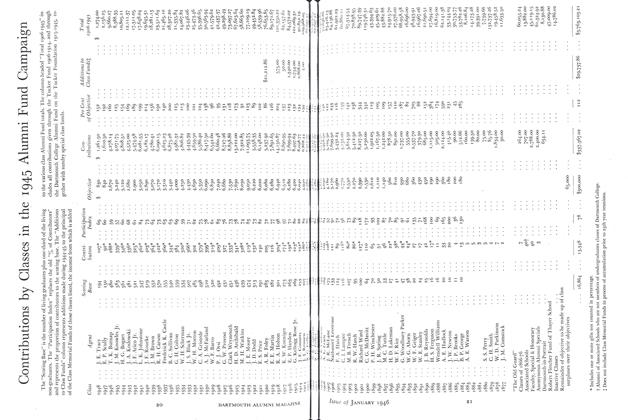

ArticleFunds for Annual Credit to Alumni Fund

January 1946 -

Article

ArticleHistoric Event of 50 Years Ago

October 1954 -

Article

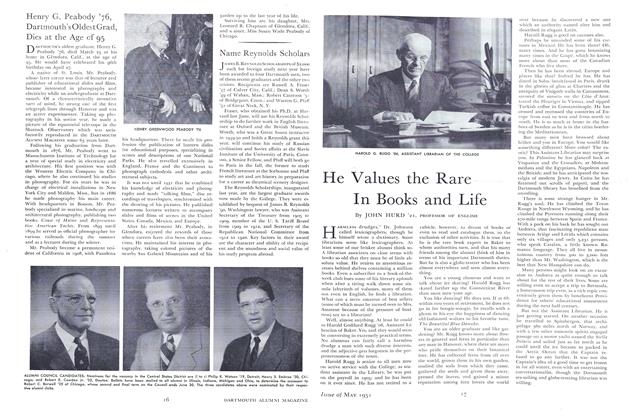

ArticleHe Values the Rare In Books and Life

May 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleGrade Deflators

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1934 By Milburn McCarty IV '35