THE Dartmouth family has filled a larger place in history than generally is known. Modesty always has been a characteristic trait, as it is now. The line originated in Italy, where it was of patrician rank, and had a magnificent palace in Venice. The name, de la Lega, as it then was written, still survives in that country, and appeared in England in official records as early as the reign of Henry II Thomas Legge was sheriff and Lord Mayor of London before the middle of the fourteenth century, and was possessed of sufficient means to enable him to loan 300 pounds to Edward III., a sum equivalent to 5000 pounds now. William, his second son, married into the noble family of Bermingham in Athenree in Ireland. The eldest of his family of six sons and seven daughters was the subject of this sketch.

William, or "Honest Will Legge," as he is familiarly known, is a striking figure, and had an adventurous and romantic career in the tumultuous period of Charles I. and Charles II. Brought out of Ireland by his godfather, the Earl of Danby, he took his first course in training for life as a volunteer under Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, followed by a term of service under Prince Maurice in the Low Countries. Apparently, he made good, for on his return he was appointed by Charles I. keeper of the king's wardrobe and, soon afterwards, groom of the bedchamber. Further evidence of. royal favOr is furnished by the fact that when the Earl of Danby was impoverished by an ex. cessive fine, the King granted his prayer for sufficient remission to enable him to carry out his purpose of leaving a legacy of 2000 pounds to his protege.

Colonel Legge, as we now find him called, was soon appointed to inspect and put in order the defenses of Hull and Newcastle. The King would have made him governor of Hull but for the protest of Lord Wentworth against the removal of Sir John Hotham, whom he had appointed to the position. Political patronage appears to have been in vogue then as now. Instead, Legge was made Master of the Armoury and Lieutenant of the Ordnance, for the first Scottish war. Some time afterwards he was accused of participation in a movement to support the King against the Parliament by means of the army. No proof of his actual, personal share in the plot was found, and he suffered nothing more serious than examination as a witness. He was implicated in a second attempt of this kind, however, and joined the forces of the King at the opening of the Civil War. Taken prisoner at Southam and imprisoned in the gatehouse, he soon escaped, which involved his gaoler in an impeachment for high treason. Henceforth we find Colonel Legge associated with Prince Rupert, with whom he continued to hold relations of great intimacy. At the siege of Litchfield he was wounded and taken prisoner, previous to the capture of the town. At Chalgrove Field his reckless courage again resulted in his capture, but he was released on the defeat of the enemy. As we recall the profanation of the beautiful cathedral at Lichfield by the fanatical Roundheads we can but sympathize with Rupert and his chivalrous friend.

The King was so delighted with Legge's conduct at the battle of Newbury that he gave him the hanger which he had worn during the day, the handle of which was of agate, set in gold. His Majesty desired to knight him with - it, but the honor was modestly declined.

Prince Rupert showed his confidence and esteem by appointing his favorite officer governor of Chester. A year later he was appointed governor of the city and county of Oxford. In the correspondence of this period the Prince addresses his friend as "Dear Will."

Colonel Legge shared in the unreasonable anger of the King against Rupert for the surrender of Bristol, and was deprived of his office as governor of Oxford, and placed under arrest, though soon released. Nothing could blunt the edge of his loyalty, however, as he soon had an opportunity to show. Having started for the Continent he learned that the King was a prisoner, and without hesitation returned to share his fortunes. He was permitted to wait upon his Majesty who, having promised not to escape, was given large liberty. The activity of a fanatical sect called the Levellers led him to be apprehensive for his safety, and to withdraw his pledge. From these dangers his faithful groom devised a plan of escape. Down a back staircase and through the garden at night, the King and Honest Will made their way to an appointed rendezvous where they were met by faithful friends with horses for the party. For participation in this flight Colonel Legge was imprisoned in Arundel Castle and was not permitted to attend his master in his last trials. The King was not unmindful of his obligations, however, and charged the Prince of Wales to be sure and take care of "Honest Will Legge, for he was the most faithful servant that ever any prince had.''

On the death of the King, Legge was released, but with loyalty unabated he accepted a commission from Charles II. to Ireland. Having been apprehended by the Parliamentary forces he was imprisoned at Plymouth, from whence he was removed to Arundel Castle and committed for high treason. Through the interposition of the Speaker he regained his liberty and was permitted to go abroad. He attended Charles II. to Scotland, where his penchant for getting into prison seemed to have followed him, as there is a tradition that the Marquis of Argyll shut him up in the Castle at Edinburg for advising Charles not to marry his daughter. Released at the request of the Prince, he attended him on his march to England and, after fighting bravely at Worcester, was wounded and again taken prisoner. His life certainly would have paid the forfeit this time but for the cleverness of his wife, who sent him a suit of charwoman's clothes, in which he so effectively disguised himself that, with a domestic utensil in his hand, he passed the guards without detection. Soon afterwards we find him in prison again through the treachery of a sneaking villain who had wormed his way into the confidence of Charles, but really was a spy from his enemies. Honest Will appears to have had as great facility for getting out of prison as for getting in, for we next find him at liberty, and engaged in the instigation of uprisings against the government and in the distribution of commissions from Charles. While thus employed he was captured and for the eighth time imprisoned. His good fortune did not desert him, however, and he soon was released on parole. Apparently, it was found to be impossible to refuse any favor to such a good fellow.

Upon the restoration Charles recalled the message of his father, in the light of which we get a glimpse of the better side of that unfortunate monarch, and offered Honest Will an earldom. Again the honor was declined, but the hope was expressed that it might be realized in the next generation. This proved to be well grounded, as his son through the royal favor became the first Lord Dartmouth. The former offices of Colonel Legge were restoŕed to him, and other marks of royal and princely favor made the rest of his life a continued romance. As an officer in the Tower, where he had been a prisoner, he had an opportunity to observe the vicissitudes of a loyalist in his generation. His intimacy with Prince Rupert continued until death. It was through the same scenes that the greatest of English novelists led Harry Esmond, but the literary fabric which he created is not a whit more romantic than the actual facts of history as experienced by our hero. It is an easy task for the imagination to make Honest Will and Richard Steele cross blades and take each other prisoners, without serious injury to either.

Perhaps the most interesting incident in this history is the marriage of Colonel Legge to Elizabeth Washington, "the great-great-aunt of George Washington," thus uniting the two families in which we are most interested. In consequence of this marriage, the Washington arms are impaled on the Dartmouth escutcheon, as shown on the monument of Colonel Legge in the old Church of the Holy Trinity in the Minories, near the Tower of London, where more than thirty of the family lie buried. They are quartered also on the arms of the first Lord Dartmouth on the bookplate recently discovered in the College Library, and the present Earl has the right to use them. As the American flag almost certainly was suggested by the stars and bars of the Washington arms, we have here a combination of incidents of surpassing interest. It is to be regretted that we know so little of the domestic life of William and Elizabeth Legge, but if we may judge from the incident in which the latter showed such ready wit and courage in aiding her husband to escape from prison, it is a fair inference that they were well mated, and that the "Father of his Country" came honestly by his masterful character. Nature makes lavish use of materials in brewing the blood of heroes, and we, who prize so highly the Dartmouth spirit, do well to make the most of our incomparable traditions.

Marvin D. Bisbee ' 71, Librarian of the College Library

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE NEW FOOTBALL

December 1906 By Homer Eaton Keyes '00 -

Article

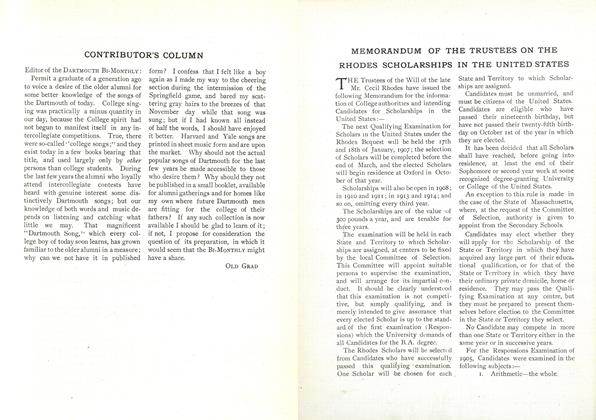

ArticleMEMORANDUM OF THE TRUSTEES ON THE RHODES SCHOLARSHIPS IN THE UNITED STATES

December 1906 -

Article

ArticleIN other columns the BI-MONTHLY

December 1906 -

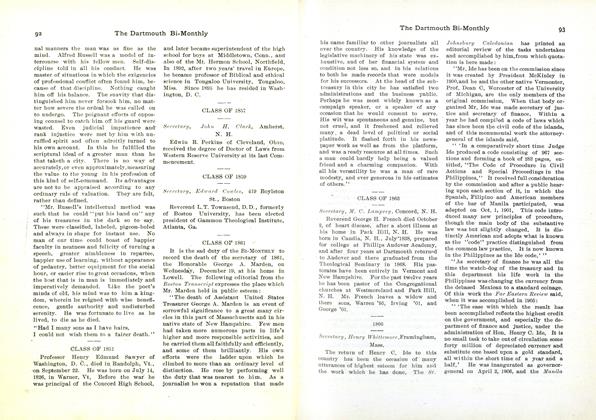

Class Notes

Class Notes1866

December 1906 By Henry Whittemore -

Article

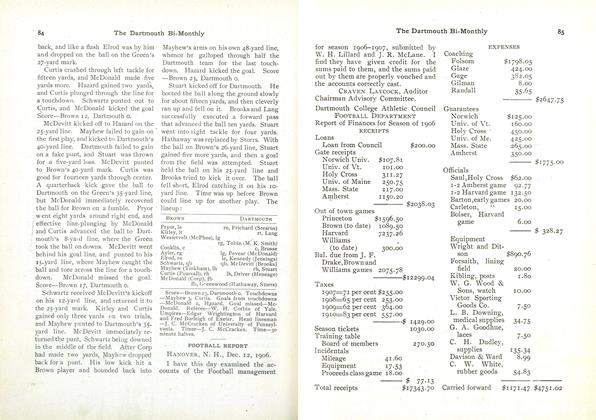

ArticleFOOTBALL REPORT

December 1906

Article

-

Article

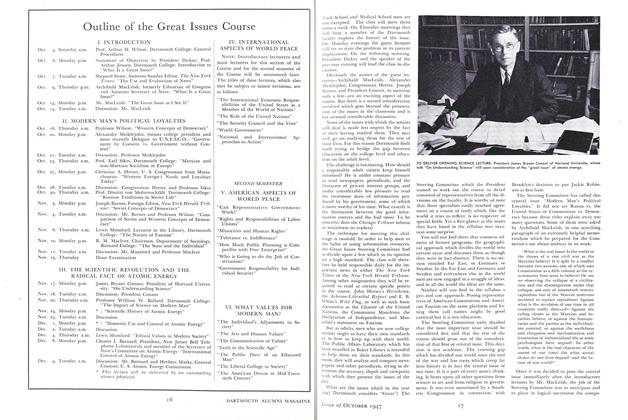

ArticleOutline of the Great Issues Course

October 1947 -

Article

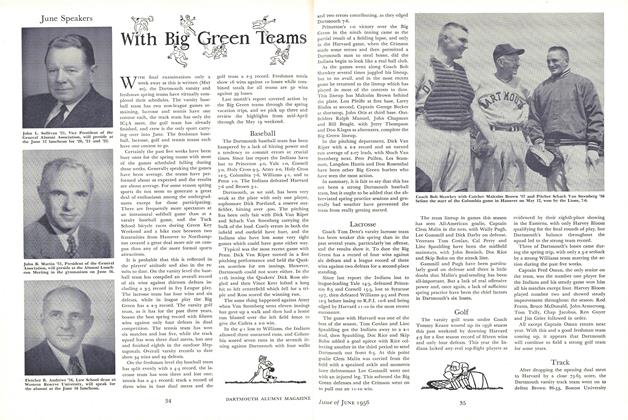

ArticleJune Speakers

June 1956 -

Article

ArticleClass Notes

MAY | JUNE 2014 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Article

ArticleDartmouth 28, Cornell 21

DECEMBER 1962 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleMen of the North

June 1931 By J. G. McIlwraith -

Article

ArticlePublication Schedule

May 1942 By The Editor