TRAINING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP BY THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF PORTO RICO

JUNE 1906 L. R. Sawyer '00WHEN the American troops landed at Guanica on July 25, 1898, it may safely be said that nearly the entire mass of Porto Ricalls welcomed them with open arms, as symbolizing the incoming of free institutions and a republican form of government; even more, with such genuine expression of sympathy and good will as perhaps never before fell to the lot of an invading army. Imperceptibly, as time went on, evident signs of dissatisfaction and unrest developed. The military government first and the civil regime later conceived and put into practice, either by order, regulation or statute, new modes of procedure,' different forms of administration, other principles of government, thereby eradicating,' altering, and in only a few cases, supplementing those then in vogue. The Porto Rican was in consequence doomed to see disappear many cherished customs and practices, the continuance of which, to many of them, seemed of primary importance.

As early as 1903 the aspirations of a large number of Porto Ricaus, in a political and social sense, had been defined in the platforms of the leading parties, arrayed as opposing bands under the designation of " Federals " and " Republicans," and in succeeding elections both one and the other the members of the Federal party subsequently being known as " Unionists "—took occasion to point out and emphasize the changes which were considered necessary in the Organic Law of the island, in order that they as a people might play, under the sheltering arm of our national government, the leading role in the formidable but not impossible task of working out their own salvation.

Three years later, in the first quarter of 1906, it will not be incorrect to state that this dissatisfaction still exists in part; though in distinction from that noticed when protest was at its height the complaints and unrest of the present day are due only in a very minor degree to misunderstanding or misapprehension with respect to the aims and purposes of the American government, as was previously the case.

Two things are-desired by the large majority of Porto Ricans. One, the possession of American citizenship, without which they consider themselves, and with reason, an alien people; and the other, greater intervention in the administration of their internal affairs. That the future will satisfy these desires, in whole or in part, seems evident when one takes into account the declarations contained in the platforms of our national parties, together with the statements of many of our most prominent and far-seeing statesmen who have the interests and well-being of this insular dependency at heart. At all events, there are now abundant reasons for supposing that as soon as Porto Rico has demonstrated itself capable, by a wise utilization of the privileges thus far granted her, of receiving a larger measure of local autonomy, the im- plantation of a liberal system of selfgovernment will not long be deferred.

Of this there can be no doubt. Had citizenship been conceded on the inauguration of civil government in 1900 it would have, by its own subtle and magnetic influence, converted thousands of lukewarm and indifferent Porto Ricans into devoted, enthusiastic supporters of the American government and the institutions for which it stands ; and it is not improbable as well that many of the acts and manifestations witnessed during the past five years and ascribed to outbreaks of anti-Americanism, would also have been averted. And now that Congress is about to legislate on this most important point, in accordance with the recommendation of President Roosevelt in his last annual message, we may expect with its bestowal to see disappear, as if by enchantment, this undercurrent of feeling, the minor chord, and to a considerable extent, the lack in compenetration of interests which characterize the environment, the conversation and the material efforts of many Porto Ricans.

It is an accepted principle that the enjoyment of American citizenship implies not only the intellectual capacity to make adequate use of the privileges attached thereto, but as well imposes upon the recipient the necessity to conform his modes of thought and action accordingly. It shall be the purpose, therefore, of this short article to point out a few of the different ways and some of the various means by which the Department of Education is contributing, in distinction from the work done lay the other departments of the Insular Government, toward furnishing the children of this island with the necessary preparation to become loyal and intelligent citizens of a free republic. A brief reference will also be made to the question of illiteracy, showing succinctly to what extent it prevailed, as shown by the census of 1899; also what this problem signifies when taken in connection with the work of this department for the near future.

At the very outset it may be said that the adult population has only indirectly been affected by the modernizing and uplifting forces and influences of which this department has shown itself the successful advocate and exponent. Yet after a lapse of six years it would be difficult to find a single grown person who did not understand better as well as appreciate more fully the purposes and ideals of the American nation as represented m her public school system.

With the reorganization of the educational department under the first commissioner of education, Dr. M. G. Brumbaugh, it became one of his main aims to provide the urban and rural districts, but especially the former, with commodious, modern, up-to-date school buildings, such as not only should satisfy the necessities of the different localities for adequate and comfortable quarters, but also furnish first-hand models of what it was desired to install and perpetuate in Porto Rico in point of school architecture, school equipment, and school sanitation. Only a few years have elapsed since the first frame wooden building, erected as an agricultural school in a small town near the coast, was dedicated, yet the important and far-reaching a dvance which has been made in this respect may be inferred when it is stated that forty-five of the sixty-five municipalities of the island are now provided with either town or rural school buildings, and in numerous instances with both. Whether in town or country, a clean, attractive and servicable school-house has arisen to proclaim the excellencies and virtues of the American school system, and though the more pretentious four and sixroom structures possess certain architectural features which add considera- bly to their sightliness, permitting the introduction of details and employm ent of materials not possible in oneroom rural and agricultural buildings, the result in either case is the same : a beacon light radiating in all directions the principles of tolerance, selfhelp and the dignity of labor, and symbolizing the development and perpetuation of those qualities and ideals which constitute the very essence of our national life.

In addition, it has been the care of the educational department not only to provide new buildings to meet the present day needs of the island, but also to secure the repair and reconstruction, whenever possible, of all buildings used for school purposes. In this way, through cooperation with the local school boards, many houses, otherwise utterly unsuitable for the accommodation of school children, have been rendered serviceable, so that temporarily they meet the wants of various communities in a very satisfactory manner.

Another noteworthy improvement has been secured in the matter of an adequate equipment with which old and new buildings, in the towns as well as in country, have been provided. Though there are still some rural schools with furniture inherited largely from their Spanish predecessors, in the main the large majority of the public schools are now equipped with modern desks, supplied with all necessary apparatus, and endowed with those material conveniences which permit school-room work to be done with a maximum degree of pleasure and a minimum of discomfort. Such as still retain traces of their former woeful state, materially and scholastically : speaking, are either those which have been less accessible to this movement of progress and improvement on account of the remote- ness of their situation, or else schools located in municipalities with very limited: financial resources, and in but a few instances, in towns the funds of which have been mal-administered. In view, therefore, of what has already been accomplished, together with the inevitable continuance and probable expansion of this same policy in the future, the following generalization seems warranted. The environment furnished the Porto Rican child attending the public schools is such that during the months or years he may be under its influence, his surroundings, both in an ethical as well as a material sense, are thoroughly democratic and liberalizing in their purposes and tendencies.

Another means which is contributing markedly, toward this same end consists in the adoption of those textbooks which shall instill, by illustration as well as through subject matter, clear and definite ideas concerning the characteristic traits of American life and customs. ' And it should be noted that while about an equal number of the texts in use are in either of the dominant languages there prevailing, already the preponderance of English text-books in the town schools, in all subjects with the exception of Spanish as a language study, is a positive fact, so that the latter may be considered the subordinate tongue for class-room work in all the important municipalities.

Since the establishment of civil government the question of English received preferent attention from the educational department, for it was held to be the most natural, rapid and feasible way of placing the inhabitants of Porto Rico in communication with the eighty millions of Americans dwelling on the mainland, and above all of opening up to the youth of the island that intimate and first-hand knowledge of our customs and institutions, without which the nature and spirit of our national life would filter but slowly and imperfectly into their minds and understanding. So it has come to pass that English now occupies a conspicuous place in the curricula of town and rural schools, and throughout the island no pupil who attends the public schools for more than one year fails to receive practical instruction in this language.

In order that a correct pronunciation as well as a practical working vocabulary may be properly acquired, American teachers (nearly 150 in number) have been assigned to the town schools, where they either pass from room to room giving instruction in English to pupils, or, as occurs in some cases, assume charge of grades of their own. Likewise these American teachers are charged with the task of supervising the English work of the native teachers who assemble weekly in the different towns for special instruction, the object of this being to prepare the Porto Rican so that he may conduct the work of his own school in English as soon as his knowledge of the language will perMit it Here it is not inopportune to mention the fact that at the close of the school year 1904-05, on the basis of a sufficiently rigid oral examination, more than fifty native teachers were awarded the special license of "English Graded" teachers, and that nearly this number have rendered service in this capacity since September of last year. As yet only a few of the rural teachers are sufficiently advanced in their knowledge of English to follow the example of their associates; many are located far from town and hence have little opportunity to practice the English they acquire, while others by reason of advanced age are handicapped to an appreciable extent in their study of a foreign language.

Other subjects contained in the course of study which may be mentioned as bearing 011 the matter in hand are: History of the United States; its Geography; and finally the study of its institutions and form of government, or Civil Government. The readiness with which Porto Rican pupils absorb ideas and the exactness of their opinions concerning matters which have been presented to them through the medium of their class-room studies, especially those just cited, often gives rise to satisfaction as well as astonishment, even among those persons seemingly most familiar with the natural capacity and intelligence of these children. So strikingly is this displayed in many instances that one is almost disposed to affirm that these pupils, in general, are as well versed in American history, geography, and civil government as are children of similar grades in the States.

A people naturally demonstrative and entering heartily and joyously into o the spirit and exterior display still evidenced on the occasion of different insular and local fete days, the children now vie with their parents in the celebration of such national holidays as Washington's Birthday, Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving and Arbor Day. It would be difficult, we believe, to determine even the relative value of the exercises held on these occasions in the United States or foresee their ultimate consequences, and much more is this the case in Porto Rico where their influence and effect can be felt and appreciated but gradually, as the rising generations reach manhood and womanhood. Thus far it seems certain that the observance of our national holidays, by the pupils of the public schools, have served to instill in their minds thoughts of patriotism and devotion for some of the most notable figures in American history, and in addition has inspired a deep- rooted affection for many of our most cherished traditions and customs.

Passing from the more purely academic side of the work conducted under the auspices of the department of education, it is well to consider for the moment the numerical aspects of the problem with which the department is confronted, as well as the age and social condition of the children over which it is endeavoring to extend its influence. The total population of the island, as given in the census of 1899, was about 950,000, of which number less than fifteen per cent were literates, a condition which — more than anv other circumstance, it is averred—rendered it inadvisable to grant the Porto Ricans full American citizenship. Of the entire popuation it is estimated that fully a third were of school age, or between the years of five and eighteen. The subsequent increase in the school population, it is calculated, brings the total number of persons of school age to nearly 375,000.

The number of children attending school at the time of the American occupation, according to statistics appearing in the report of General Davis for 1899, was 21,000, whereas for the past scholastic year (1904-05) 67,886 pupils were in attendance, leaving a difference of more than 300,000 children who by the school law of the island are eligible for enrollment in the public schools. It may safely be presumed, however, that many of this number, during the past seven years, have already enjoyed school advantages, for the per cent of children continuously in attendance throughout the _ eight years over which the curriculum of primary instruction extends (three years in the rural schools) should be considered as only a small fraction of the total enrollment; so that at least 100,000 children, and probably more, have enjoyed school privileges for one year or more under the American administration of Porto Rico. The opinion has also been advanced, the exposition of which appears in full in the report of the commissioner of education for 1904-05, that with facilities for accommodating 100,000 children the public school system of the island would be adequate to meet such demands as might be placed upon it for some years to come.

Concerning the actual duration of school life of pupils who have thus far been enrolled, it has been found that those living in the rural districts, comprising one-half of the entire enrollment, are unable to continue in at- tendance on an average of more than two years, their pecuniary condition too often requiring that they seek employment, at an early age, in the coffee or sugar fields, In the towns, to a considerable extent, a nearly analogous condition prevails, for after the fourth year the decrease in enrollment is marked. This point is perhaps best illustrated by the statement that about 55,000 pupils of the total enrollment of 67,886 for the past school year were between the ages of five and thirteen, from which it may be deduced that the question of a livelihood has to be faced very early by the large majority of Porto Rican boys and girls.

The fact should not be overlooked, however, that with the advance of material prosperity and the consequent improvement in the social and intellectual standards of the mass of the population—a transformation which is even now taking place rapidly and perceptibly, in nearly every aspect of the life of this people—the requirements of the school system can not remain fixed but must continue elastic and readily adjustable, in order to meet the rapidly changing needs of the Porto Ricans in their inevitable desire for longer and fuller utilization of public school privileges. It seems certain that the duration of school life of the Porto Rican pupil will prolong itself considerably in the immediate future, and the time is not far distant when the public school system of the island will show the same rounded development, with its full complement of children in upper and lower grades as well as generous attendance in high and special schools, as characterizes its counterpart in the United States.

The necessity for popular education, in order to correct and eradicate many of the most conspicuous shortcomings and racial inheritances which were transmitted to them as a result of their historical past, is realized by Porto Ricans in general, and they lend generous and willing assistance in extending its uplifting and moralizing influence. The insular legislature contributes liberally for its maintenance, voting twenty-eight per cent of the annual budget for this purpose Private endeavor, directed to the end of furthering its beneficial effects, is becoming more and more frequent and spontaneous. In short, the school system of Porto Rico, by reason of the grand work it has already done and by what it gives promise of accomplishing in the future, has won a sure and lasting place in the confidence and regard of all Porto Ricans —better still, will unquestionably constitute henceforth a priceless and unrelinquishable asset of the body politic of this beautiful island of the Caribbean.

Little can be added to the hopeful statements of the first commissioner of education in his apt but brief delineation of the Porto Ricans, and the future will take to itself the task of proving the correctness of his optimistic outlook contained in the following words : "These people are patriotic. They love their beautiful island. They long to see it prosperous, enlightened, exalted. They love the American nation, » .... in proportion to the enlightened understanding they have of her institutions and of her purposes to Porto Rico. The national sentiment gradually is growing with the insular pride, and will eventually be one, as the destinies of the two peoples now are one."

L. R. Sawyer WO, Formerly Chief of the Division of Supervision andStatistics, Department of Education, Porto Rico

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH COLLEGE FIFTY YEARS AGO

June 1906 By Amos N. Currier, '56 -

Article

ArticleBASEBALL

June 1906 -

Article

ArticleCONFERENCE OF MODERN LANGUAGE TEACHERS OF SECONDARY SCHOOLS

June 1906 -

Article

ArticleTHE weeks of spring have swiftly passed and the Commencement

June 1906 -

Article

ArticleTRACK ATHLETICS

June 1906 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1880

June 1906 By Dana M. Dustan

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

February 1962 -

Article

ArticleProfessor Mirsky

September 1975 -

Article

ArticleBaseball Weather Brings Bulldozers

MAY 1996 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWinter Carnival

February 1947 By C. E. W. -

Article

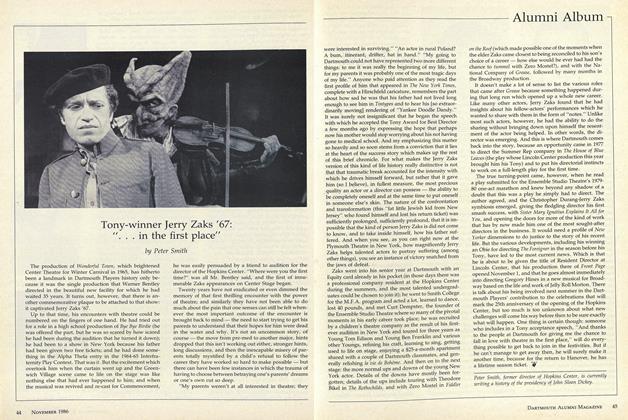

ArticleTony-winner Jerry Zaks '67: "...in the first place"

NOVEMBER 1986 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1936 By Robert P. Fuller '37