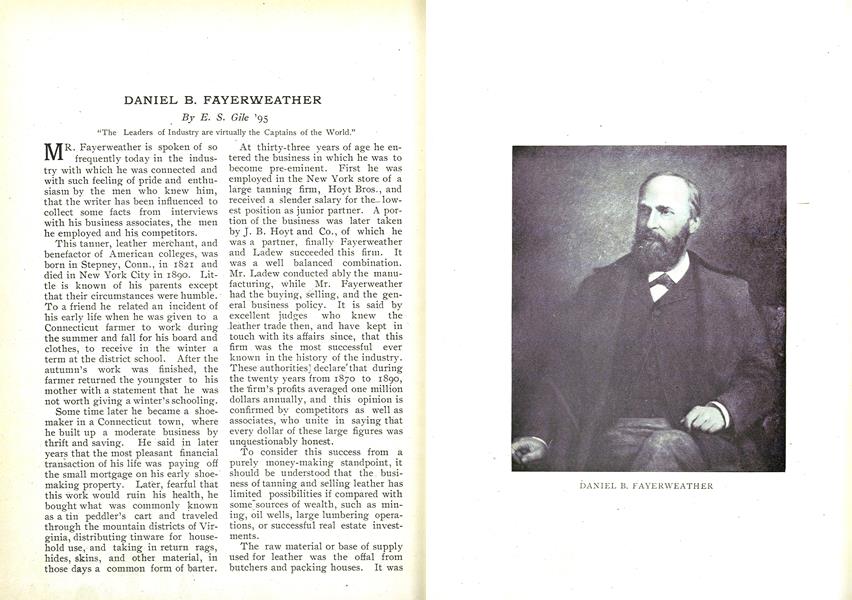

MR. Fayerweather is spoken of so frequently today in the industry with which he was connected and with such feeling of pride and enthusiasm by the men who knew him, that the writer has been influenced to collect some facts from interviews with his business associates, the men he employed and his. competitors.

This tanner, leather merchant, and benefactor of American colleges, was born in Stepney, Conn., in 1821 and died in New York City in 1890. Little is known of his parents except that their circumstances were humble. To a friend he related an incident of his early life when he was given to a Connecticut farmer to work during the summer and fall for his board and clothes, to receive in the winter a term at the district school. After the autumn's work was finished, the farmer returned the youngster to his mother with a statement that he was not worth giving a winter's schooling.

Some time later he became a shoemaker in a Connecticut town, where he built up a moderate business by thrift and saving. He said in later years that the most pleasant financial transaction of his life was paying off the small mortgage on his early shoemaking property. Later, fearful that this work would ruin his health, he bought what was commonly known as a tin peddler's cart and traveled through the mountain districts of Virginia, distributing tinware for household use, and taking in return rags, hides, skins, and other material, in those days a common form of barter.

At thirty-three years of age he entered the business in which he was to become pre-eminent. First he was employed in the New York store of a large tanning firm, Hoyt Bros., and received a slender salary for the lowest position as junior partner. A portion of the business was later taken by J. B. Hoyt and Co., of which he was a partner, finally Fayerweather and Ladew succeeded this firm. It was a well balanced combination. Mr. Ladew conducted ably the manufacturing, while Mr. Fayerweather had the buying, selling, and the general business policy. It is said by excellent judges who knew the .leather trade then, and have kept in touch with its affairs since, that this firm was the most successful ever known in the history of the industry. These authorities] declare'that during the twenty years from 1870 to 1890, the 'firm's profits averaged one million dollars annually, and this opinion is confirmed by competitors as well as associates, who unite in saying that every dollar of these large figures was unquestionably honest.

To consider this success from a purely money-making standpoint, it should be understood that the business of tanning and selling leather has limited possibilities if compared with some sources of wealth, such as mining, oil wells, large lumbering operations, or successful real estate investments.

The raw material or base of supply used for leather was the offal from butchers and packing houses. It was a supply over which no one had control and which fluctuated in price from day to day.

The manufacture of leather was delicate, slow, painstaking business, in which small errors caused great losses. The selling of the product, as well as the buying of the raw material, was highly competitive, and there were no firms and no individuals who had special advantages except from ability.

An iron mine may be a mountain of wealth, indestructible, permanent, waiting for its owners to market it. Mr. Fayerweather's business was more like the oak from whose bark he made his leather. The oak roots perform useful work silently underground and can be compared with the important, far-extending branches of a leather business, devoted to the slimy collecting of hides from numerous sources and long distances, and working them through the first tanning processes. The upper branches of the oak treee enjoying pure air and sunlight somewhat resemble the more agreeable selling department, "equally far-reaching in divisions and territory. Each of these great departments, as well as the manufacturing, were of vital importance and dependent on each other. The tanning business, like the oak, was a thing of life. It could be ruined by a thunder bolt or a gale, and it could also die of dry rot.

The accumulation of large wealth under such conditions is more remarkable than in any other lines of industry and finance.

The principles which Mr. Fayerweather employed in his work ar of unusual interest, and although he has been dead nearly twenty years he is frequently spoken of, not only as the most successful man who ever lived in the leather trade, but as the man whose business principles were the highest yet reached in this industry or within the observation of those who knew him.

He worked, too hard, never taking recreation from the cares of business, and almost always at his office from 7:30 in the morning until late in the afternoon. He gave very little time to social life and was slightly known outside of his immediate banking and business circles.

Those who knew him say that he paid the fairest prices for raw material, sold his finished product as low as his competitors, quality considered, and was more liberal than any of his contemporaries in paying his employees, and most liberal in granting credits.

It is puzzling, at first thought, to make all these statements harmonize with large yearly profits, but there are some special features to be considered.

Every department of this house was at the front of the whole industry in efficiency and economy ; moreover, wisdom was used in selecting the product to exactly fit the needs of those who bought it.

Mr. Fayerweather, through hard work and intimate knowledge, often saw clearer than the buyer what he needed. This fine adaptation of selections of the product was a benefit to the purchaser and increased the profits of the seller.

It was a fundamental principle of this firm's tanning department to make leather, not only to suit the manufacturer of shoes and belting, but also to have honest value for the final consumer. To get these results they wished the best selection of hides, taken off in the most careful manner, and were willing to pay higher prices for these than anyone else. Oftentimes after examining a lot of hides, Mr. Fayerweather would pay a quarter of a cent more than the agreed market price, because the seller had used extraordinary care in the take-off, which practice he wished to encourage.

This liberal policy of buying gave him first choice of almost every desirable lot of hides offered. It influenced his competitors to sometimes try to bid against his prices to get what Mr. Fayerweather wanted. At times when this trick was attempted it was found to be useless, as he would bid higher and higher than his rival, and sometimes made the remark that he would pay $1.00 a pound, if necessary, for what material he wanted. A few experiences of this kind led the trade to respect his judgment as final, and both buyers and sellers came to him freely for advice on market conditions.

There is no question that he sold his product on very fair terms and was the first man" of prominence in the leather trade to establish a policy of reducing prices after a sale had been decided upon, because the market had gone down and against the buyer. When the market went up in favor of the buyer, he always delivered promptly every pound of merchandise at the rate agreed upon and never asked any favors, but time and again those who bought from him got bills at one-half to two cents per pound lower than the agreed-upon price of the sale. This gave him a position of confidence which no one ever rivaled.

He was rarely mistaken in his judgment of human nature, and in picking out young, struggling firms that needed liberal credit, seldom made a mistake. He was a great force in building up new firms, by granting almost unlimited credit, where his competitors were hesitating to allow even a small line.

There are many large, successful houses today who admit that they owe their start to Mr. Fayerweather in selecting them as honest and likely to succeed. There is every reason to believe that these small firms selected to receive large credit were treated in the matter of price as well as their larger and more wealthy competitors.

Mr. Fayerweather often said that a small, struggling firm plainly could not afford to pay a higher price than the rich and powerful.

The writer was recently talking with a member of a firm who used to call weekly at Mr. Fayerweather's New York office and was also the recipient of extremely liberal credit. One morning before his weekly call, he had consulted his books and found he owed $260,000. In his interview he asked if he had not exceeded the credit which should be allowed him. Mr. Fayerweather replied in his quiet way, that this was a sort of moral credit and that when the limit was reached he would notify the debtor ; in the meantime devote no worry to this large sum, but do the best he could to make his business a success.

This is one of the many instances that could be recounted in the shoe and leather trade today. Mr. Fayerweather believed that it was his duty to help the success of those who bought from him. He would never try to sell a large amount of merchandise on what he believed was a declining market, believing that it would result unsatisfactorily with his customer, preferring, to stand the loss himself. He not only had the power to deserve and hold the confidence of his customers, but he also had the gift of making these firms realize that to take any advantage of his liberality and confidence would be a serious matter. One case recently came to my attention, where a buyer of not very high reputation had purchased a large amount of Mr. Fayerweather's leather and had paid for it. The market declined, and knowing something of Mr. Fayerweather's policy of reducing prices, he sent word through the broker in the transaction that the quality was not up to the standard. This was the kind of a message that would instantly arouse anger. Mr. Fayerweather immediately notified the purchaser that if he would ship back all the leather, he would return the money and hereafter their dealings were entirely closed.

This story is told of his anger with another buyer : A Philadelphia manufacturer of fine shoes had the privilege of sending his buyer to Mr. Fayerweather's warehouse and making his own selections for the purpose of securing the best. By error one day an employee took this buyer to the wrong store-room and he made his choice from second quality stock ; strangely he returned in a few weeks to get the same opportunity. Mr. Fayerweather, disgusted att his lack of knowledge, rather irately ordered him out of the building, saying that he did not want any such ignorance in his establishment.

He believed in his right to dictate his own business policy and to put his own prices on his own merchandise. He looked with great disfavor on any buyer criticising his quotations or making offers below his prices. He argued that if the prices placed on his goods were too high, he would soon find it out and reduce them himself, without the suggestions from any outside source. He completely dominated his own business policy.

In the matter of employment of labor, and his salaried men, he was extremely liberal, paying higher prices than any of his competitors, and at the end of each year gave a bonus out of the profits to everyone connected with his departments.

He did not look with favor on requests for increases in salary, but watched after each individual himself, being sure that he was receiving higher wages than anyone obtained for similar service. Among his employees and business associates he demanded efficiency duriug business hours, but his discrimination rarely went beyond this requirement.

He was as quick and accurate in selecting good men around him as in granting credit. To this skill is attributed a fair share of his success.

Mr. Fayerweather was a man of very quiet personality and simple, modest habits.

Nearly all his pleasure in life was contained in his work. When his New York home . was completed, a friend asked what he intended to buy for paintings. Mr. Fayerweather made a characteristic reply that he feared he could not see as much beauty in works of art as in sides of his Flintstone Oak Sole Leather, and he had a mind to use the latter for wall decorations.

Few people knew much about his business or much of his wealth until after his death. In the New York banks where he was a director his fortune was greatly underestimated. His gifts to charity during his lifetime were known by a few to be extremely large, but donations were always made on the condition that nothing more would ever be obtained from him for the same cause if his name should be made known publicly. One of his partners recently told me of the large gifts made in this quiet way to churches, charities of different kinds, and it is believed that he gave away an enormous fortune in frequent generous instalments. It is also known that he paid large debts for relatives to keep them out of financial disgrace.

At a time when his firm used to buy notes for investment, if he made an error in judgment and got a worthless note, he would pay for this error himself and stand the whole loss , out of his personal account.

The firm's business very early got to such a successful state that it was not a question of endeavoring to make more money, but a problem as to how exemplary a manner the affairs could be conducted. This was probably his chief aim in life. One who was closely associated with Mr. Fayerweather says he was influenced to give his millions to American colleges, by the keen feeling of personal loss caused by his own lack of education. By aiding the institutions of learning, he felt he was doing the greatest general good that could possibly be accomplished by his wealth.

It is also said by good judges that he intended to change his bequests so that his name would not appear publicly as connected with college buildings, and that a substantial share of the gifts should be in the form of scholarships to undergraduates who needed assistance. It is believed by the authorities for these statements that his failing health prevented him from making these changes in his will.

To illustrate the esteem in which Mr. Fayerweather was held by his competitors and associates in business, we quote as follows from the report of a meeting held in the New York leather trade near the time of his death. One contemporary made the following statement: "He seemed to take pride in serving a customer so that he would always feel perfectly at ease in dealing with him. He was a man of very quick perception. I have purchased large bills from him in less than five minutes—enough to supply me. for six months. He would conscientiously and faithfully fill a contract, no matter whether the market advanced or declined. He gave me a great impetus and a lesson. Whenever the market turned against him he fulfilled his contracts to the letter. One time it turned against me. Mr. Fayerweather thought the conditions were too severe, and on our next meeting he said : "The market has gone down ; I will reduce the price to the present quotations." The remarkable part of this last statement is seen when the reader knows that Mr. Fayerweather tanned leather and also man- ufactured it into belting, for sale throughout the country. The gentleman making the comment above bought Mr. Fayerweather's leather in the rough and manufactured it into belting to compete with him in the markets of the country.

Another said : "In all the relations of life he bore himself so absolutely without reproach and made a record so perfect and so clear of blame that there was never a spot or blemish on his name. This can be said of few men, but it can be said of him without reservation. His modesty, which has been spoken of, was a trait that was conspicuous in him from the beginning to the end of his life. We knew him when he was without fortune, when he was a clerk employed at a slender salary. We knew him when he was the richest among his compeers in the trade—there was no change in his demeanor, no arrogance, no pride ; he was always the most simple, unpretentious, and kindly of men." Another spoke as follows : "Mr. Fayerweather's career furnishes an example of probity which every young man in the trade ought to study and emulate. He was rigidly and scrupulously upright in all his dealings with his fellowmen. If he sold a customer an invoice of leather, and the price advanced twenty per cent before he delivered it, he would take more pains to send the man an article of the very best quality than he would if delivering it at the current price. (Mr. Fayerweather explained this policy thus : 'The buyer will naturally be watchful and expect a poorer quality, so we will agreeably surprise him ; then what is culled out and replaced by better goods can be easily sold in the advanced market.') There wasn't a mean streak in his nature nor a sinister thought in his mind. If he said he would do a thing, the verbal promise was as binding upon him as if it had been engrossed on parchment and sworn to. And this man, with such a perfect sense of rectitude, was the greatest favorite of fortune that was ever engaged in the leather business. The moral is apparent : There is profit as well as glory in being honest."

To sum up Mr. Fayerweather's life, the following, copied in part from the epitaph on Eleazar Wheelock's tomb, might be appropriate :

By Toil, Honesty, and Generosity, he gained great wealth.

For the advancement of mankind, he gave his riches.

Man of Business !

"Go if you can and deserve The sublime reward of such merit."

DANIEL B. FAYERWEATHER

FAYERWEATHER ROW OF DORMITORIES

E. S. Gile '95 "The Leaders of Industry are virtually the Captains of the World."