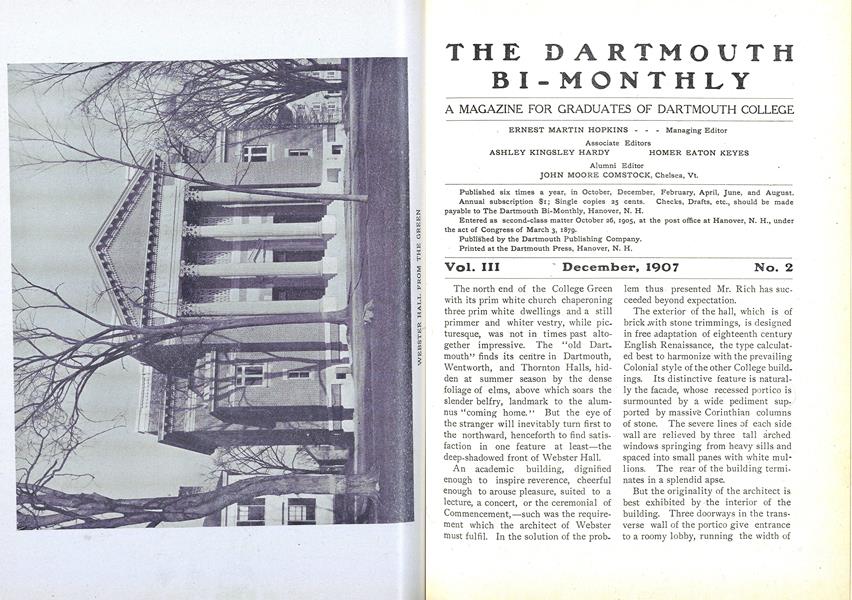

The north end of the College Green with its prim white church chaperoning three prim white dwellings and a still primmer and whiter vestry, while picturesque, was not in times past altogether impressive. The "old Dartmouth" finds its centre in Dartmouth, Wentworth, and Thornton Halls, hidden at summer season by the dense foliage of elms, above which soars the slender belfry, landmark to the alumnus "coming home." But the eye of the stranger will inevitably turn first to the northward, henceforth to find satisfaction in one feature at least—the deep-shadowed front of Webster Hall.

An academic building, dignified enough to inspire reverence, cheerful enough to arouse pleasure, suited to a lecture, a concert, or the ceremonial of Commencement,—such was the requirement which the architect of Webster must fulfil. In the solution of the problem thus presented Mr. Rich has succeeded beyond expectation.

The exterior of the hall, which is of brick .with stone trimmings, is designed in free adaptation of eighteenth century English Renaissance, the type calculated best to harmonize with the prevailing Colonial style of the other College buildings. Its distinctive feature is naturally the facade, whose recessed portico is surmounted by a wide pediment supported by massive Corinthian columns of stone. The severe lines of each side wall are relieved by three tall arched windows springing from heavy sills and spaced into small panes with white mullions. The rear of the building terminates in a splendid apse.

But the originality of the architect is best exhibited by the interior of the building. Three doorways in the transverse wall of the portico give entrance to a roomy lobby, running the width of the building. The panelled woodwork of the walls is enameled white, the arched ceiling is white, the floor is of marble tile. At each end of the lobby a stairway leads to the galleries. In front, leather covered folding doors give admission to the auditorium. Here the structural capabilities of steel have rendered possible an arrangement varying widely from the basilican type which the outward plan would seem to demand. Nowhere appears a column or other intermediate support to obstruct the view or diminish the effect of space. The form is virtually that of the Greek cross, the members emphasized at the corners by Corinthian pilasters that sweep from floor to ceiling and give support to heavy beams of stucco. Save at the north "end of the hall, which is occupied by; a broad platform, capable of transformation into a stage, steep galleries span the distance to pilaster. The whole scheme presents a masterly example of straight line composition whose possible monotony."is skillfully obviated by the semi-circular window mouldings and the great triple arch that fronts the semi-dome of the apse.

The arrangement is one obviously combining dignity and simplicity. Color and lighting are such as to ensure cheerfulness. The walls are of gray plaster, sand finished. All wood finish, together with the stucco of pilasters, cornices, and mouldings is of white. The ceiling, too, is white, but deeply coffered in rectangular panels that by day give an agreeable play of light and shadow. At night, the hundreds of tiny incandescent bulbs with which the, edges of these panels are studded flood the entire auditorium with a brilliant but perfectly diffused illumination. The whole effect is intensified, yet balanced by the deep note of color in the mahogany tone of seats and benches and the rich red of aisle and platform carpetings. To add to this, portraits of prominent alumni and benefactors of the College have been extracted from their hiding place in the library, at once to adorn and to find due honor in Webster Hall. In time, the number of these portraits may be increased, memorial tablets may be erected, other records find fitting disposition ; so that in the passing of the years Webster Hall shall come to be recognized as the heart of the College, type of its history, guardian of the visible symbols of its traditions.

It is a welcome announcement to Dartmouth men that relations are to be resumed with Williams next fall. No good is gained by reopening discussions closed. Behind us lie years of invigorating rivalry. Differences are swept away and the slate is wiped clean by Dartmouth's advances and Williams' courteous acceptance of them. Competitions which have stood representative of the best in sports in the past are again to take place, in the old spirit. The correspondence was :

"F. W. OLDS, M.D., Williams Athletic Council, Williamstown, Mass.

"DEAR SIR: Believing that the temporary suspension of athletic relations between Williams and Dartmouth would prevent various minor differences from assuming proportions which might make a healthy rivalry between the two colleges impossible, the Dartmouth Athletic Council last year passed a resolution to that effect, a copy of which was at the time transmitted to yoUr Council.

"We regret the fact that owing to what we now know to have been a misunderstanding on our part, the Dartmouth Council acted in the matter alone, rather than in conjunction with the Williams Council, which we feel may have tended to place Williams in a false light. If in fact it did have any such tendency it is a matter of sincere regret to us.

"At the present time we know of no conditions which would in any way interfere with a healthy rivalry between the two colleges, and it is the unanimous wish of our Council, and is the judgment of both our undergraduates and alumni as well, that athletic contests between the two colleges be resumed.

"Accordingly I am instructed, by vote of the Dartmouth Athletic Council, at its last meeting, to communicate to your Council an official statement of our readiness and desire to renew athletic relations whenever there may be a similar desire on the part of Williams.

"Trusting that whenever the two colleges meet again in athletic sports their contests will continue to be marked by the same spirit of friendly college rivalry and mutual good feeling that has always characterized their relations in the past, and which has long been regarded at Hanover as one Of Dartmouth's most highly prized traditions, I am, very sincerely yours,

"(Signed) C. E. BOLSER, "Secretary Dartmouth Athletic Council."

The answer of the Williams Athletic Council follows :

DR. CHARLES E. BOLSER, Secretary Dartmouth Athletic Council, Hanover, N. H.

"DEAR SIR : I beg to acknowlege receipt of your communication of December 17, and am pleased to inform you that the Williams College Athletic Council agrees with you as to the desirability of a renewal of athletic relations between Dartmouth and Williams, and to that end has authorized its football manager to arrange with the football manager of Dartmouth for a game to be played during the season of 1908 on some date to be mutually agreed upon by them.

"Trusting the renewed relations will be always amicable, and the old spirit of healthy rivalry be restored, I remain, on behalf of the Athletic Council, very truly yours, "FRANK W. OLDS, President, "Williams Athletic Council."

The December number of the Educational Review contains an article by President Van Hise of the University of Wisconsin with the title "Educational Tendencies in State Universities," which is of such general interest that we present a summary of the main points:

State universities were first established in the South, later in the Middle West, where they have perhaps reached their most typical development. The most characteristic difference between these institutions supported by taxation and the colleges or'N universities which derive their income from private endowment, is that the former feel a special obligation to the community in which they are situated. The state university studies the practical problems of the state - agricultural, industrial, political, social,'moral, and hygienic. In addition to the college of liberal arts, the university establishes such courses and schools as the demand of the people of the state for training in various professions and practical activities makes desirable.

"But in solving the problems of the state," says President Van Hise, "the university lends a hand in the solution of the problems for other states and sections. In proportion to the resources, I believe larger results for the world will be obtained by that institution which recognizes local responsibility than by the institution which feels no special 'obligation to the community in which it happens to be located, and has simply before it as its ideals, pure culture, pure learning, pure science, with little or subordinate thought of immediate service."

Another distinction between the state universities and the private foundations, that the clientele of the former is local, while that of the latter is sectional, is tending to disappear as the state institutions become larger and more important. Indeed, some of the best known of the private foundations .draw more than half their students from the state in which they are situated. Thus at Pennsylvania only thirty-one per cent come from outside the state; at Columbia, thirty-six per cent; at Harvard, forty-seven per cent, while at Michigan, the only state university which has been for a long period of considerable size and influence, forty-five per cent of the students come from outside the state. A large number of other state universities have an important clientele from other parts of the Union and from foreign countries. The graduates of the state universities are scattered from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the alumni associations are already making their influence felt in the matter of non-resident attendance.

President Van Hise then passes to the subject of coeducation, which, apparently settled seme years ago, is now entering upon a new phase.

"It is necessary to remember that in the older universities of the Middle West coeducation began, not in consequence of a theoretical belief in it upon the part of the officials of those institutions, but in spite of such belief. The reasons which led to coeducation were purely economic. The western states in these early days were too poor to support two high-grade educational institutions. Yet the justice was recognized of the women's demand that they have equal opportunity with the men. There was no way to afford such opportunity but to adopt coeducation, and this was the solution which was gradually forced upon the older universities of the Middle West."

Once introduced, coeducation proved immediately successful, and was established as a matter of course in the newer state universities. The sentiment in its favor became so strong that Stanford and Chicago were originally founded as coeducational institutions, and many colleges for men opened their doors to women.

At present all the state universities north of Mason and Dixon's line, and west of the Mississippi are coeducational with the exception, of Louisiana. In the southern states east of the Mississippi, however, the principle has not been so generally adopted. There are three times as many women in the privately endowed coeducational institutions as in the state universities. It is to the latter, however, that President Van Hise confines his discussion. In the colleges of liberal arts of thirteen important western state universities the women constitute 52.7 per cent of the students, and outnumber the men in seven of the thirteen. This is true only for the colleges of liberal arts; if all departments are included the women are greatly outnumbered in all cases.

President Van Hise denies that the presence of women students has caused any deterioration in the intellectual standards of coeducational institutions, and supports his position by the opinions of other state university presidents, and by the fact that the average scholastic record of the women has so far been higher. than that of the men. In graduate work, however, "it does appear to be a fact that the percentage of women who are willing to work at the same subject six hours a day for three hundred days"in the year is much smaller than among the men. But this quality is essential for success in research."

The rapid increase of women in the colleges of liberal] arts in the universities has created certain educational problems which are at present demanding a solution. The first is appropriately called "the problem of social affairs." In the early days of coeducation the young women desired to utilize their educational opportunities to the fullest extent and were bent upon proving themselves the intellectual equals of the men. But at present "with the increase in numbers of men and women with no very serious purpose there is undoubtedly a tendency among the women to regard as successful the one who is attractive to the young men — in other words social availability rather than intellectual leadership is regarded by at east a considerable number of the young women as the basis of a successful college course."

This problem of social attraction has as a counterpart one of intellectual repulsion. "Certain courses have become popular with the women so that they greatly outnumber the men. As soon as this situation obtains there is a tendency for the men not to elect these courses, even if otherwise they are at. tractive to them. Similarly, there are certain courses which are naturally taken by a large number of men, perhaps with reference to their future careers, and there is a tendency for the women not to elect these courses because of this fact. Languages illustrate the first, and political economy the second."

As has been said above, in several of the state universities the number of women in the colleges of liberal arts already greatly exceeds that of the men

If this tendency continues there is a possibility that some of the colleges of liberal arts in the state universities, not the universities as wholes, may in large measure cease to be coeducational by becoming essentially women's colleges." This problem has been handled at Stanford and Wesleyan by limiting the number of women admitted, at Chicago by segregating the sexes for the first two years.

To meet the situation in the state universities, President Van Hise advises the establishment of separate divisions for men and women in such subjects as would normally be attractive to both. This has already been tried to a limited extent, and is indeed' provided for in the charter of the University of Kansas.

It is perhaps unnecessary to add by way of comment, that if the natural segregation of the sexes is recognized by the establishment of separate divisions and courses, coeducation as it has hitherto been understood will have ceased to exist.

For the past six months, Princeton has been enjoying something between a South American revolution and a French duel; but now after much shouting and considerable red glare of rockets, the air is clear again, the combatants have fallen upon one another's necks, and the dove of peace broods where nested the squabble.

It all came about through what the objectors construed as a dictatorship demanding a democracy, — in itself a disturbing paradox, made more paradoxical by the fact that the said democracy was to be achieved by a process of leveling up rather than of leveling down. In short. President Wilson, noting among Princeton students an apparently ' dangerous schism arising from the! withdrawal of considerable numbers of upperclassmen into exclusive clubs, conceived the idea of abolishing these small decentralizing units, and substituting in their place a number of larger units to be denominated "residential quads.'' Into these quads the undergraduates were to be injected, there to eat, sleep, and have their being, emerging however for purposes of common recitation.

This was an enlargement of the club idea in that it made every one a club man: it possessed the color of the English college mode, — though some professed to perceive aniline in the dye. The cost of thus democratizing the college was estimated at the neat sum of two million dollars, or in the neighborhood of two thousand dollars per preliminary democrat.

At Commencement time the scheme was approved by the Princeton trustees and hurled bomb-like into the midst of unsuspecting students, faculty, and alumni. Scheme and manner of presentation, being thoroughly revolution, ary, produced the inevitable counter revolution, whose minute-man forthwith swapped rod for gun and opened a vigorous bombardment. If, in the general tumult, any were silent, no one observed the fact. The marshalled columns of the alumni weekly bristled with inter, rogation points and exclamations; even the shades of invoked.

The seventeenth of October, 1907, will be historic in the annals of Nassau. On that day the trustees capitulated, hauled down their newly erected flag, and passed it over to President Wilson with full permission for him to wave it as he would: they, however, were done with it. Thus, for the time being ends the democratization of Princeton.

Yet there is no reason to assume that Princeton men have any objection to democracy. In fact, they no doubt pride themselves upon possessing that estimable quality. Probably, however, they prefer their own brand to that which it was desired to impose. Possibly, too, they realize that general good fellowship, like total abstinence, is difficult to obtain by fiat. Birds of different feather find it nearly as impossible to flock together as did Cholmondley's bird of a feather to flock all alone by himself.

Furthermore it is usually a safe plan for a college administration to take the students measurably into its confidence before legislating for'their social good. It would be a poor Princeton man indeed who would not see his club sunk to the piazza rail in the deepest depths of Carnegie Lake rather than that the spirit of his college should suffer. But he wants to have a hand in the ceremonies. Such happens to be human nature. As youngsters we prefer our own to the parental fingers in early tooth extraction: as grownups, when one of our members doth offend we wish at least to superintend the subsequent amputation.

And, after all, what does college democracy mean ? Surely very much the same thing as democracy everywhere, — equality of opportunity. Not every man finds his true level in college: not every man finds his true level out of college. The best that can be done is to give to each his chance, let him fight his fight and then eat the fruits of battle whether they be sweet or whether they be bitter.

After last year's formally stated policy on the part of the fraternities at Dartmouth that it was for the best interests of all concerned to postpone chinning season from October until the beginning of the second semester, the present occurence of the annual undergraduate spasm so early as December may occasion some surprise. The fact of the matter seems to be that postponement until the second semester proved not for the best interests of all concerned. If October was too early, February'was too late. The Freshmen, thrown more than usually upon their own resources, grew restless and often discontented. The average Freshman goes home for the Christmas holidays; the Easter recess may find him almost anywhere. To return to the fold, duly decorated with e emblem of undergraduate approbation, means a good deal: from mid-year to Commencement was a long time to wait. Hence the compromise which resulted this year in a December chinning season. The change seems to have worked well: as large a percentage as usual was pledged to various fraternities: each fraternity secured its fair quota of men: heart burnings and discoids were reduced to as low a minimum as is consistent with the interest of the event. Above all, the fortunate Freshmen may wear their badges home for the holidays.

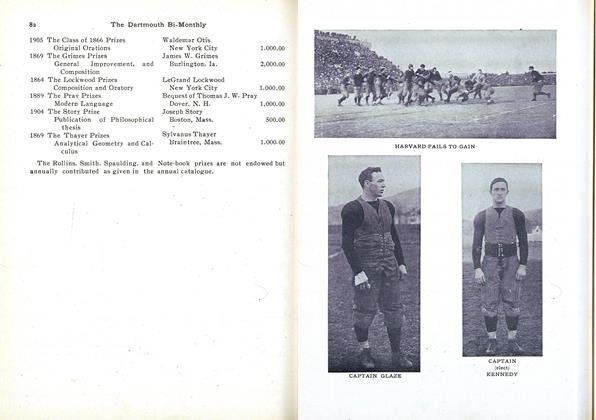

The football schedule of 1907 ended with large satisfaction to all Darmouth men, and though the season has been history for some weeks now, the satisfaction remains. For half a decade Dartmouth has been playing the game of football, asking odds from no one. For the five years we have a proud record of successes over Amherst, Williams, and Brown, with one victory in three games over Princeton, and two wins and two even games in the Harvard series. Much as we value the accomplishments of a single year we are more concerned with the consistency of our record over a term of years. We prize the increment of athletic achievement. Because of this even more than for the temporary pleasure of decisive victory, we congratulate ourselves on the fitness of the recently completed season to succeed t hose gone before. Ably captained,skillfully coached, the team was made up of men individually expert and collectively forceful. Football knowledge was superimposed on football instinct, and from this combination the logical result followed. The 1907 team ranks as one of Dartmouth's greatest teams.

The growth of the College in numbers, the increase in the instruction corps, and the greater complexity of the curriculum have all worked to completer and more complete social segregation of the two groups, - faculty and students. Plainly no member of the faculty could entertain any considerable body of the students; likewise, only rarely have groups of students endeavored to entertain members of the faculty. The College Club, therefore, has made an experiment, in the weeks between Thanksgiving and Christmas, and invited in turn, in a series of three receptions, the two upper classes and the associated schools, the Sophomores, and the Freshmen. All of the faculty were invited to each reception. The results have exceeded expectations, and the opportunity of wider acquaintanceship has been welcomed from both sides. The isolation of Hanover has so many advantages over a city location for a college that every effort ought to be made to remdy any drawbacks. Lack of social opportunity has been one of these, and the College Club, in so far as it can, is striving to supply what has been lacking.

The resignation of Professor Justin H. Smith of the department of Modern History, which was tendered to the trustees at the close of the last academic year, was accepted by them at the last meeting, though with sincere regret. His research work and writing in connection with his work on phases of Mexican and of Canadian history have become more and more absorbing, and have demanded from him more than could be given while retaining his position in connection with the College. The release for which he asked, therefore, has been reluctantly granted. The cordial interest of his friends in and of the College follows Professor Smith in his chosen work.

The BI-MONTHLY is indebted to Professor C. H. Morse for the football pictures printed in this issue.

WEBSTER HALL FROM THE GREEN

WEBSTER HALL INTERIOR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

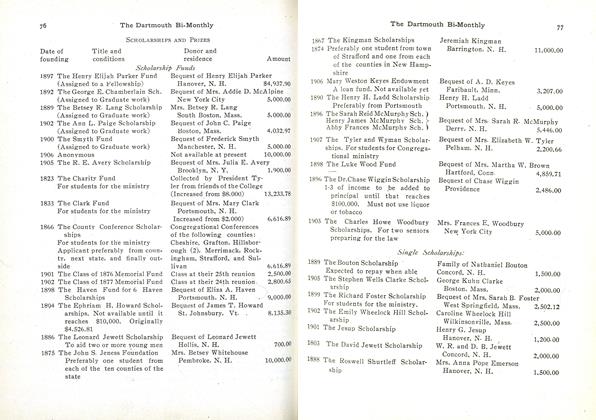

ArticleTHE CHANDLER AND OTHER ENDOWMENT FUNDS FOR SPECIFIED USES*

December 1907 -

Article

ArticleTHE HARVARD GAME

December 1907 By Eugene R. Musgrove '05 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

December 1907 -

Article

ArticleSCHOLARSHIPS AND PRIZES

December 1907 -

Article

ArticleFRATERNITY ELECTIONS

December 1907 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OP 1874

December 1907 By C. E. Quimby