BEFORE SETTLING DOWN to review a few good books for this month, I should like to call your attention to the publication of Hardy's "lost novel" called An Indiscretion in the Life of an Heiress. The clue for its discovery was furnished by my friend Paul Lemperly, book collector par excellence, of Lakewood, Ohio, who, for many years, has been aware of the existence of the novel, and has one of the three known copies in America of the New Quarterly Magazine for July, 1878, where the story first appeared anonymously in print. Professor Carl J. Weber of Colby College, from the clue given him by Mr. Lemperly, has run down the facts, written an excellent introduction, and edited the book now available from the Johns Hopkins Press. A most important and necessary item for all students and lovers of Thomas Hardy.

Desert and Forest, by L. M. Nesbitt. Jonathan Cape, London. 1934.

Hell-Hole of Creation, by L. M. Nesbitt. Alfred Knopf. New York. 1935.

This excellent book will probably receive little ballyhoo in this country but it is the best travel book that I have read for many a moon. I believe that for sheer interest and suspense I should rank it above Bertram Thomas's Arabia Felix, published in 1932, a book which described the crossing for the first time of the Empty Quarter of Arabia.

Mr. Nesbitt, an English engineer, and two Italians, Pastori and Rosina, in 1928 were the first Europeans to traverse successfully the Danakil country in Abyssinia, a rectangular piece of country 350 miles long and about 100 miles wide, sunk in places to 300 to 400 feet below sea level, located between the Red Sea and the eastern spurs of the Abyssinian plateau. In the northerly part of the Danakil country, they explored a range of active volcanoes, "belching sulphurous smoke over the glittering waters of a string of salt lakes."

"Even though it were to cost me my life I would see this Danakil, the country that so far had baffled all efforts at its exploration," decided Mr. Nesbitt. There had been attempts before. In 1881, thirteen Italians led by Biglieri and Giulietti had all been massacred by the savage Danakils. Three years later Bianchi, Diana and Monari met a similar fate, as did all other subsequent exploring parties. It was in this country that 1500 Italian soldiers were massacred in 1896. II Duce may know what he is doing, but his soldiers would be well advised to keep out of the country of the Danakils.

In the first place the country itself is a veritable hell. "The temperature was 168 degrees Fahrenheit when we started out. We peered everywhere with straining eyes, but there was no sign of a man walking anywhere amongst the infernal stones. To the east and south, the lava fields extended further than the eye could see. Northward, the left-hand cliff of the torrent stretched into the distance, and to westward, we could see nothing but the last curve of the grim ravine whence we had just come. The whole ghastly landscape was quivering under the noonday sun, a waste of scorching rocks without the faintest sign of life anywhere. We searched carefully, but Wolde Johannes (one of their natives) was nowhere to be found At some time past noon we saw these three men (who had volunteered to search for Johannes) returning carrying their friend between them. The poor fellow had become insane." Water holes were infrequent and in this terrific temperature water had to be sipped continuously.

In the second place the Danakils are probably the most savage race living. Three members of Nesbitt's party, all natives, were killed by them. Many times the lives of Nesbitt and his companions hung by the veritable hair. That they lived to tell the tale is due to the immense patience and resourcefulness of Mr. Nesbitt, who had had much previous experience in all parts of the world dealing with natives and travelling by caravan.

For this journey starting from Addis Ababa, capitol of Abyssinia, they planned to journey from south to north with pack animals and with the simplest fare and equipment. They took fifteen natives, twenty-five camels, four mules, and twelve old rifles with only 200 rounds of ammunition. On their trip they killed no one but instead lavished presents and bribes to the various chieftans and their tribes. Peaceful measures alone, combined with superlative tact, carried them safely through. On March 14, 1928 they started out, and about three months later reached Massowa having crossed safely, after incredible difficulties, this savage country. Chapter 25, Suni Maa, is a masterpiece of descriptive writing, and I recommend it hereby to all compilers of prose anthologies.

Since writing the above I have received an interesting letter from Edward Garnett which throws some light on Mr. Nesbitt's "dry chronicle style" as Clifton Fadiman put it in his review of the book in The NewYorker. Mr. Garnett writes: "I'm delighted that you appreciate so much Desert andForest. I discovered the author as the book was translated by him from the Italian! and he only half remembers his own tongue. It was very strange and full of linguistic mistakes, but the quality came through, and Cape got an author named Rutter to revise and rewrite in places the MS."

This book is required reading for all who read travel literature.

Lions Starve in Naples, by Johan Fabrieus. Little, Brown & Co. 1935.

Rambaldo Fittipaldi, day dreaming young lawyer of Naples, finds scope for his genius in a bankrupt circus. Finally his dreams come true after his successful and comical efforts to liquidate Gottfried Storm's circus, and in his efforts to save Saul and his sixty lions from being separated, he reaches supreme heights.

The author has well depicted the Neapolitan spirit in his novel. Moreover, in Saul, he has created a tragic figure, and in Saul's devotion to his lions, he becomes almost an elemental force. After reading this novel one wonders if the general pression which grips the world will not destroy the age old institution of the circus. One hopes not.

City Editor, by Stanley Walker. Frederick A. Stokes. 1934.

Stanley Walker is well equipped to write this book as for the last seven years he has been the city editor of the N. Y. HeraldTribune. He writes genially, and with a brusqueness which is very effective. I found the first half of the book better than the last which seemed thrown together in almost unseemly haste.

This book is a sort of hodge-podge of information for the would-be newspaper man. It explains Walker's pride in his craft, and at the same time, it annihilates several popular opinions about the press and about reporters. Walker suggests that a newspaper office is not like the one depicted in that rowdy and entertaining play The Front Page. Gossipy as the book is about news writing, reporting, etc., the book may be read with amusement' and profit by the general reader who here will learn how the daily miracle (accepted by us as a matter of course) of a great city paper is brought about. Finger nail sketches of several prominent reporters past and present abound. Especially interesting was Walker's estimate of the late Chailes E. Chapin, the efficient city editor of the Evening World, who died in Sing Sing in 1930, while serving a life sentence for the murder of his wife.

Further information on Chapin while in Sing Sing may be gleaned from Edward F. McGrath's I Was Co?idemned to the Chair.

An Oxonian Looks Back, by Lewis R. Farnell. Martin Hopkinson. 1934.

1 he late Lewis R. Farnell was connected with Oxford for over fifty years, beginning as a resident B.A. interested in archaeology, and ending as Rector and Vice-Chancellor. He was connected with Exeter College and resigned from active academic service in 1928. So this book is not only the autobiography of a classical archaeologist, with a background of ten years of archaeological exploration in Greece, the Near East, Sicily, etc., but it is also a history of Oxford University of the past half century. For both reasons the book interested me. His life was without exceptional outward interest, though his canoe trip from Donau-eschingen in Baden in 1886 to Vienna 535 miles down the Danube was not without its dangers, but more important to me was the point of view of a man who spent his life as a classical scholar in one of the oldest of our world universities.

I shall take the space only for one quotation illustrating his attitude toward collegiate sports, which in English universities have never suffered from over-emphasis. On page 142 he writes: "Thus, as the games-cult waxed in its intensity, I felt for. many years that our academic intercourse both with our juniors and seniors became somewhat flatter and duller, and there was a flagging of interest in intellectual conversation. Not many of us could be said 'to warm both hands before the fire of life'. Athletic ardour can partake in the joy of high living, but only if it is not in bondage to winning and to the long servitude of training, and does not talk or read too much about itself. To play and to enjoy a good game is consistent with deep study and scientific discovery; but to think too long and too anxiously about it both before and after the event dulls the mind's edge. The material prosperity of Oxford in these latter days is in far less danger than its soul, which will not be saved by winning the boat race. Its only way to salvation is to follow the Mazdean precept 'to think right thoughts.' It is not athletics, but sport-idolatry that endangers the soul of Oxford." This seems to me to apply even more to our American sport-and-winning-mad colleges. What "right thoughts" are, of course, is another and more difficult matter.

"Oxford," he writes, "needs the help of the best men that she can attract to her, to quicken intellectual power among the leaders of our people, and to cherish under any form of society a paramount regard for the things of the mind."

There are many interesting sketches and impressions of many scholars of England and Europe, some statesmen, writers like Morris, Pater, Wilde, Walter Raleigh, and other interesting men. Not a sensational book, but it is sure to interest those who like unobtrusive autobiography, and those who are interested in education, and particularly those Americans who have had connections with Oxford, casual or real.

The Cingalese Prince, by Brooks Atkinson. Doubleday, Doran. 1934.

One cannot but envy Mr. Atkinson his voyage in the freighter Cingalese Prince. The immense expanses of the ocean afforded him the detachment he needed from the madness of life in the years of the Great Depression. Mr. Atkinson found himself at great peace. "For what is progress but an itch?" he thought, in Cosmic Yankee fashion, of the mad scramble ashore. Here for an apartment dweller at least was adventure. "For it is adventure," he writes, to find that the world is large and lonely and that the wind can blow at hurricane force and that sunlight is a free commodity." "It is an adventure," he continues "to find that some men do not parcel out their freedom in twelvemonth units to the city landlord, but lead traveled lives through the small ports of the world." Sorry he was to get back to New York four months later.

Taking Montaigne's advice to travel without prejudices, Mr. Atkinson visited Japan, Shanghai, Hong Kong, many out of the way ports in the Philippines and East Indies (a six thousand ton freighter goes where the Empress of Britain cannot), to Penang and Colombo, across the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, and home. This is not a guide book but it reveals the change in spirit of a dramatic critic in a voyage to find meaning in a universe where there seems to be none. Author of a book on Thoreau who once said meaningly that "he had traveled a great deal in Concord," Mr. Atkinson is as thoughtful, but less metaphysical, a traveler as the famous naturalist he so much admires.

I had forgotten, too, that Mr. Atkinson could write so well. This book represents a very decent stride in the caliber of Mr. Atkinson as a stylist. The skyline promenade he once made of the White Mountains apparently was a good preparation for a promenade around the world on the decks of the Cingalese Prince. An excellent book to be placed on your shelves with travel books you deem worth keeping.

In Time of Peace, by Thomas Boyd Minton, Balch & Co. 1935.

The outstanding qualities of this book are sincerity and honesty. These qualities were outstanding in the character of the author. In Through the Wheat, the novel of the war, one felt that William Hicks was but a palpable mask of Thomas Boyd. William Hicks also walks through the pages of In Time of Peace. I do not mean that this novel is autobiographical as to incident, for it is so only in part, but Hicks is still Thomas Boyd, struggling to.make a living, struggling to belong, and trying to understand the forces which precipitated the chaotic years since the war.

I shall not give a lengthy resume of the novel. After working in a machine shop, Hicks gets a white-collar job as a reporter. He marries on a small salary, his wife, has a baby, and the economic struggle gradually wears them both down. Finally after his wife gets a job writing advertising they live more luxuriously, going to many drinking parties which Hicks really loathes. His paper fails and he finds himself out of work. He lines up for work at a big factory where no help will be taken on. Ordered off, the workers stand their ground and are shot down, and the author ends his book: "His chin dropped, waggling from self-pity. But no, by God! Back of the guards stood the police, back of the police the politicians, back of the politicians the Libbys, and behind them all the sacred name of Property. In the name of property men could be starved to death, and if they even so much as raised their heads, there was war. Hicks gritted his teeth. If it was war again, he was glad to know it. He at least had something to fight for now."

Whether this was Boyd's experience I do not know, but in any case it is symbolical of the struggle which was going on within himself in his hatred for the injustices of our industrial civilization. For Thomas Boyd, War and Capitalism were synonymous terms. He hated war and it followed as the night the day that he hated capitalism which in his opinion survived only through imperialistic expansion and through war. The suffering of the great masses of men in our industrial age since the war began to wear on Mr. Boyd, who really was an idealistic young man of sturdy American forebears who were early settlers in Ohio, and he perforce must, like Siegfried of old, try to kill the Dragon. He was well aware of the Dragon's power, and in the last talk I had with him, he talked of dying on the barricades so near was the revolution to him. He was a fine American citizen, wounded in action fighting for his country in October, 1918, at Blanc Mont, but his country, in his opinion, had no use for him unless he fit himself into what he considered its cruel and unjust system.

He died suddenly on January 27, 1935, and his country, which might ultimately have jailed or shot him for being true to his best and most decent instincts, lost one of its most promising writers, and citizens, of his generation.

In Time of Peace is not a proletarian novel and so disappointed Mr. Granville Hicks. Mr. Hicks being a Marxian critic has a set formula for a work of fiction, and woe betide any book, no matter what its purpose or no matter how good, if it fails to fall within the criteria of his Communistic criticism. These are ironical years for many of the genuine veterans of the foreign wars who actually saw some fighting. They have been called the "lost generation" and this book is the tale of one of them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER SUBMERGED

May 1935 By Richard J. Lougee '27 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

May 1935 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

May 1935 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1904

May 1935 By David S. Austin, II -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

May 1935 By Arthur E. McClary -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1935 By Harold P. Hinman

Herbert F. West '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1936 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1952 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleA Dartmouth Bookshelf

January 1958 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1958 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleNorth Country Fair

February 1937 -

Article

ArticleNine Other Programs This Summer Range from Executive Decision-Making to Russian

APRIL 1963 -

Article

ArticleGeorge T. Angell, 1846 The Friend of Animals

MAY 1968 -

Article

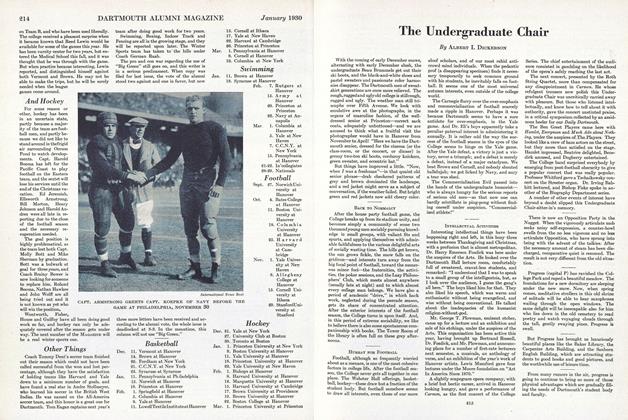

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January, 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

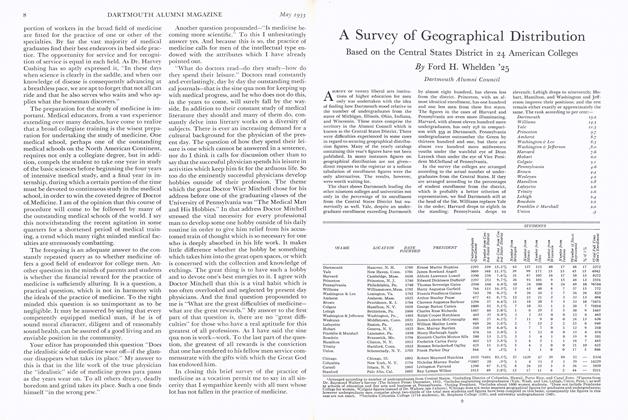

ArticleA Survey of Geographical Distribution

May 1933 By Ford H. Whelden '25 -

Article

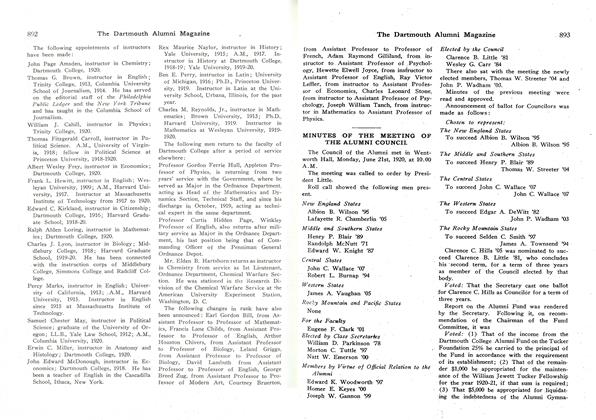

ArticleMINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

July 1920 By HOMER E. KEYES