An interesting meeting was held in Dartmouth Hall Friday morning, February 22, to commemorate Washington's birthday, and in anticipation of the International Hague Conference. President Tucker presided, Doctor Waterman offered prayer, and Professor Robert Fletcher, .Mr. W. K. Stewart, Doctor H. S. Person, and Mr. E. B. Watson spoke.

Professor Fletcher, the first speaker, emphasized "Washington's Influence in Shaping the American Policy of Neutrality." He said in part: "America, — the United States,— the New World, has many times astonished Europe and the old-timers of the Old World.

"The Declaration of Independence has caused most profound changes in political institutions and social and national development, not only in Europe but around the world. In the War of 1812 the victories of American frigates humbled the pride of the mistress of the ocean. During a brief later period American clipper-ships beat the world in fast sailing, and carried American commerce into the remotest seas. An American steamboat first established the commercial success of steam navigation of inland waters. Soon afterwards it was an American steamship which first crossed the Atlantic. The battle of New Orleans was won against the British veterans of the Napoleonic wars by American riflemen behind the cotton bales; and the American rifle was handed about the courts of Europe as a remarkable weapon. The iron-clad Monitor after the fateful combat with the Merrimac, wrought consternation among the nations, since all the vast wooden navies of the world were helpless before such an engine of war. Captain Mahan's great work on 'The Influence of Sea Power,' has dictated the later naval policies of the world powers.

"Before Washington's day there was no consistent custom, law, or national conscience concerning neutrality in war." The speaker here cited some instances; then read a few paragraphs from Washington's farewell address presenting his sound views relating to international obligations in this matter; then a paragraph from Hall's "International Law," showing how that when Genet, the French ambassador in 1793, issued letters of marque to American citizens to fit out privateers against British commence, in violation of American sovereignty and American neutrality, Mr. Jefferson, Washington's secretary of state, formulated in broad terms the American doctrine of neutrality which was enacted into law by the American Congress in 1794, and amplified by a later act in 1818. "Thus the United States took the initiative in a distinct enactment which has practically become international law, undoubtedly largely shaped if not dictated by Washington. It is noteworthy also that the prescient statesmanship and political hopes expressed in Washington's farewell address are likely to reach a large degree of realization in the International Conferences at the Hague."

Mr. Stewart spoke on "Militarism in Germany." "Germany is the greatest military power in the world,'' said he. "Well over one-third of the total national expenditure is devoted to the army and navy. Every citizen has to perform active military service for two years. The result is an army of 600,000 men, commanded by 25,000 officers. The recent 'Koepenick affair' has disclosed some of the most glaring weak- nesses of this huge military system. The officers enjoy exaggerated prestige, and occupy a social position to which they are hardly entitled by their ability or usefulness. They are frequently insolent and conceited, extravagant in their habits and, if recent revelations are to be believed, immoral in their lives. Exemption from civil arrest, which is a privilege of the military class, is a source of much trouble. The private soldiers are well drilled, but seem to perform their work in an unintelligent, mechanical fashion. Partly as a result of this training the Germans appear as individuals to be lacking in initiative and adaptability. The civilians stand in complete awe of the military authority. This inbred submission to authority has been potent in preventing the full development of a representative system of government. The only remedy for these conditions is disarmament in some form or other. Unfortunately there is little hope for that at present.''

The "Economic Costs of War" were discussed by Doctor Person: "The economic costs of war are of two general classes, those resulting from the actual conduct of war and those resulting from the condition of 'armed peace.'

"Costs of the first class are the more conspicuous, but those of the second class are insidious and constant. The important items pertaining to the first class are: The destruction of capital, comprising capital devoted to peaceful purposes as well as capital devoted to purposes of war; the sustenance of those engaged in the economically unproductive activities of war; the absolute destruction of labor power because of soldiers killed and maimed; the temporary destruction of the labor power of all those withdrawn from productive acitvity for purposes of war; and the general disorganization of industry occasioned by the sudden withdrawal from the performance of their usual functions of large amounts of capital and labor, and by the sudden lessening of the demand for many commodities. So-called 'boom' times experienced by a belligerent country are a deception: the 'boom' is in the manufacture of commodities to be consumed in war; individuals may gain, but it is through the redistribution of existing wealth; society loses.

"The important items pertaining to the second class of costs are: the constant replacement of capital goods which become, obsolete, capital goods highly specialized for purposes of war and useless for other purposes when obsolete; the sustenance of men, in a standing army and navy, devoted to unproductive activities; and the cost to society of the withdrawal of enlisted men from productive labor. Germany, for example, forfeits constantly a labor force roughly equal to that of all young men between the ages of twenty and twenty-four residing in those coast states of the United States from Maine to New Jersey inclusive."

Mr. Watson spoke as follows: "The problem of the 'Near East' is perhaps the greatest obstacle to the immediate adoption of arbitration in the affairs of Europe. The problem centers about the sultan of Turkey and his possession of Constantinople. For nearly six hundred years he has lived in most uncordial relationship, not only to the Christian nations of Europe, but also to the large and unwieldy Christian portions of his subjcets. "Although in his relations to Europe the sultan has had reason to be suspicious of every great nation, his chief contest has been with Russia. For more than a century Russia has pursued a policy of slow aggrandizement upon Turkish territory, and has furthermore aimed to get exclusive right of interference in the internal affairs of the empire on behalf of Christian subjects. To offset this action on the part of Russia, the countries of Europe have gradually formed what is known as the "European Concert." Their purpose has been carried out mainly in the treaty of Paris of 1856, and in the treaty of Berlin of 1878. This latter treaty is especially valuable as a forerunner of the present peace movement, for in it the great nations of Europe forced upon Russia and Turkey a settlement of their war disputes with a view to a permanent peace basis. In the relation of the sultan to Europe, this treaty has so far been final, and has made of his state a sort of neutral plaything in the hands of Europe.

"It is to be noticed, however, that with each action of the European Concert the sultan has lost either land or power. It is to be doubted that he will always submit peaceably to this kind of arbitration. Those that know him best say that when he has been pushed to the farthest extremity,— that is, when he has been invited to step back across the Bosporus into Asia Minor,— his sullen submission will change to a desperate struggle, in which the Turkish soldier of fanatic power will present a problem that is too much for diplomacy to settle.

"The relation in which the sultan stands to his subjects is likely to prove more difficult yet. His barbarous cruelty of six centuries they cannot forget. The murder of twenty thousand Greeks on the island of Chios, the Bulgarian atrocities of the seventies; the recent Armenian massacres; and the more recent repetition of the Bulgarian atrocities, in 1902 and 1903; these are but special instances of what on a small scale is happening in some part of the Turkish empire, generally in the provinces, as a regular method of maintaining order. This problem has so far proved too much for the European Concert. It has professed to deal with it by proposing reforms. Its actions in carrying these reforms into effect have in each case been late, or, as in the case of Armenia, entirely lacking.

"Although this problem of the Near East is a menace to the peace of the world, it is at the same time a problem in which arbitration has so far played an important part, and which at least demands that every effort should be made for peaceful settlement."

With the singing of "America" the exercises were concluded.

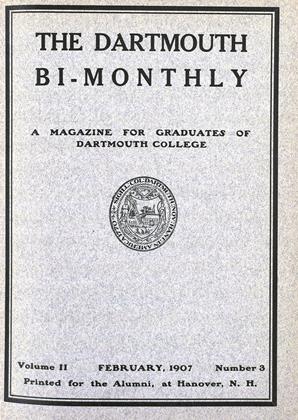

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSOME CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDENT LIFE IN CAMBRIDGE

February 1907 By G. F. -

Article

ArticleTHE PRESIDENT'S TRIP TO THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

February 1907 -

Article

ArticleTHE President of the College has recently returned from an extended

February 1907 By GEORGE H. HOWARD -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

February 1907 -

Article

ArticleTHE THIRD ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES

February 1907 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

February 1907 By Lucius E. Varney