ADDRESS BEFORE THE ALUMNI BY THE HONORABLE THEODORE E.BURTON

Byway of introduction Mr. Burton referred to the fact that his father was a graduate of Dartmouth, and congratulated the College upon the distinction and varied activities of its alumni, comparing them to the alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge, England, and said in substance:

"In shaping the political and social institutions of a people, and determining its place among the nations, there are two conspicuous forces, sometimes acting in harmony, and sometimes in antagonism. In any event, they are closely intertwined, so that it is difficult to tell by analysis what results are traceable to each. The one may be called moral or personal. Its influence depends upon the quality of the inhabitants, especially the early settlers, and is greatly increased or diminished by the form of government adopted, traditions of the past, by education and by prevalent ideals of patriotism and morality. The subsequent increase of population by immigration or accession from pother countries modifies the type of the original stock.

"The other force may be called physical. It depends upon graphical. location of the state, the area, the climate and soil, means of communication with other countries and within its own borders.

"I should be far from saying that courage, devotion to country, or a lofty moral standard are the creations of atmosphere and geographical surroundings ; or that a love for the beautiful exists only where there is a view of gorgeous landscapes, or blue waves dashing against the shore, though all these qualities are greatly stimulated by favoring physical conditions. If we were compelled to balance the advantages which have made our country what it is, we might be constrained to admit, with some abatement of national pride, that nature, or physical conditions, have done most for us. Perhaps this is true of every nation on earth. In any event, it will be conceded that nowhere in the world have the two formative factors coincided so auspiciously as here.

"Mr. Bancroft in an eloquent paragraph states that from North to South all along the Atlantic coast, the settlers who reached our shores came breathing a desire for civil and religious liberty. In comparison with those who have settled other lands, too, they were far more intelligent; though almost all grades of advancement in education and refinement were represented. The beneficent influence of the early population has never found a more splendid illustration than in the original settlers of New England, whether their sphere of action be considered as limited to her narrow boundaries, or as extending over the broader fields to which her sons have migrated.

"But, had our geographical area been confined to the territory east of the Alleghanies, there would not have been a chance for more than a struggling nation, probably attached to some other country. Again, the energy and progressive spirit so characteristically American would have been lacking. However lofty their ambition, if those who sought liberty and increased opportunities in the new world had found a .lodgement in a tropical climate, their vigor would have been enervated and it would have been impossible to have made the record which they have made. If this had been a land made up of various islands, the bonds of union between them could not have been so strong. We are fortunate in that all of our continental domain is within the temperate zone, and also that it is the north temperate zone, so that we are on great lines of communication with other countries having a high degree of civilization. But given the conditions which existed—a boundless continent having a helpful climate and a fertile soil awaiting settlement, a stalwart people actuated by a desire for greater liberty and opportunity ; and add to these factors contemporaneous movements for the sertion of popular rights, and . certain results were inevitable.

''First: It was certain that the colonists would break away from the mother country—independence was their assuired destiny. In the colonial period, divers reasons for.separation arose; creating the desire or disposition to live apart, such as the remoteness of the colonies from the mother country and the resulting difficulties of administration , the development of a selfish purpose to use the colonies for the advancement of the mother country, manifesting itself in unjust commercial regulations and the cruel repression of manufacturing, also the . clash of colonial interests with British policy which was constantly involving the new settlers in conflicts not their own. Other reasons gave the strength to accomplish separation, such as their own experience in self-government, the stalwart self-reliance which arises from a hardy pioneer life,—a factor which has many times modified the very framework of our political development,—and the military discipline acquired in wars with the Indians and the French.

"The pioneer is always of an independent spirit and detests autocratic power. He is ready to assert his rights,- and so wherever he has gone forth into any part of the world, his pathway has been a road which leads to freedom. He has thrown off the yoke of his native land unless it rested very lightly upon him, or an all-pervading attachment has bound him to the country of his birth, or in some cases, where he is so situated by the nearness of a powerful antagonist that the protective shield of a stronger power is necessary to defend from injury.

"Many of the colonies of Great Britain, such as Canada and Australia, are virtually free commonwealths, with their own tariffs and internal policies. Only last year a large measure of autonomy was granted to a South African colony which less than seven years before was engaged in a deadly conflict with Great Britain.

"It was impossible that the sturdy ideals of the colonists, and their insistence upon their own rights, would suffer them to remain under the yoke of a government three thousand miles away, in which corrupt and selfish interests often exhibited themselves, and almost always to the disadvantage of the colonists. In an era when old time privileges were being destroyed and the people were asserting their rights, wherever there was an independent spirit it was impossible to satisfy these inhabitants of the new world with any form of government except one over which they had control and in which they were to determine the institutions to be adopted.

"Second: It was inevitable that they should be united. It is unnecessary to dwell at length upon this very obvious fact. Their future could not reach its full fruition unless the different colonies not only acted in concert, but were one people. Local jealousies and the insistent desire for the freedom of the colony and of the individual, could not long prevail against a spirit of nationality prompted by a desire for their own defence and better development, and by anxiety to possess that honor and respect from the other 'nations of the earth which was only possible in case there was one country.

"Third: It readily followed that this would be a country in which a popular form of government would be adopted and free institutions would prevail. In its very beginnings, no population so varied ever migrated with such a uniformity of purpose. The early history of the colonies was contemporaneous with a great uprising in Europe against despotism. The strongest aspiration of the colonists was for individual freedom, for a development under local control which had already reached unprecedented proportions and gave infinitely greater promise for the future. In the same connection it was certain there would be no binding connection between state and church. The church had been to many of the colonists the most offensive form of oppression, and they prized liberty of conscience.as a jewel of great price. Then too, there was such a variety of religious organizations and beliefs that no agreement could be reached as to the particular one which should be selected. Catholic and Protestant alike were represented, and especially the many forms of Protestantism. The one religious denomination whose members had been most aggressive in directing forms of civil policy adhered to the principle of the independence of each of its congregations.

"Fourth: It was inevitable that there should be expansion across the continent. A strong and militant people full of ambition would not allow vast areas of unoccupied land which stood in the way of their natural expansion to belong to the domain of a stranger king. When once the advancing settlers crossed the Alleghanies into the Mississippi valley, and cast their eyes upon that magnificent and fertile empire, they were sure to possess it, and having expanded thus far, it was also certain that they would cross the more lofty mountains and not rest until they had reached the Pacific.

"Fifth: It was certain that there would be an unparalleled economic development. No part of the earth under the control of one government possesses such a variety of treasures of the field, the forest and the mine, with such unparalleled opportunities for distribution. Yet at the beginning the full effect of the possibilities for the acquisition of wealth did not exercise so potent an influence in our political and social life as might have been expected. Indeed, the effect of predominant interest in commercial and industrial growth did not become fully manifest until our own day.

"Democracy reached its climax in the Revolutionary period as was illustrated by the Articles of Confederation and the constitutions of the various states under which legislative authority was predominant. Elections were frequent and every form of restraint upon executive power was carefully secured. The Constitution has been termed a reactionary document. Frequently in the determination of the boundary lines between freedom and authority the pendulum swings from one side to the other. The Constitution resulted from a realization of the weakness arising from an undue predominance of legislative government, also from a revival of attachment to the form of the English government and from the general adoption of the Common Law of England.

"It is well to give attention to the fact that ours is not an advanced democracy. Unlike some of the republics of the olden time, there are two legislative chambers. The executive has the veto power which can only be over-ruled by a two-thirds vote of both houses. The membership of one body continues for six years, and beyond these checks upon hasty or injudicious legislative action, there is that institution peculiar to our country, the supreme court, which can decide whether legislative or executive action is in harmony with our constitution, and can set aside solemn decrees of congress or orders of the president, if they are not. It has been said of our government that it is truly a formidable apparatus of provisions to prevent change. It is a system under which the popular will shall rule, but it it is secured with equal care that the popular will shall be deliberately expressed. There is ground for the impression that its founders thought it was not the first but the second voice of the people, which is the voice of God.

"In the first fifty years under the Constitution, forces, many of which had been potent in securing independence, were exerted for the growth and enlargement of democratic ideas. The pioneer again showed his influence for the doing away with privilege, and securing the most absolute equality- The repulsion which in the later time existed between the North and South, manifested itself between the East and West. The change from the almost exclusive pursuit of agriculture to a greater variety of pursuits, showing itself in the growth of cities and the industrial class, led to the removal of restrictions upon the right of suffrage. It must be said that the natural tendency during the whole period of of our political existence has been in this direction. But of late there has been a counter movement for the increase of executive power by reason of the greater confidence in its promptness and efficiency.

An election held a few days ago which resulted in changing the form of government of the leading municipality in a state west of the Mississippi River, under which the legislative body was abolished and the sole control of the city placed in the hands of the five commissioners, is an illustration of this tendency which is decidedly worthy of attention.

"It has not been so much the advocacy of any political theory as the more perfect means of communication, the close relation between different sections, and the necessity of conducting operations on an enormous scale, which have tended to make the boundary lines of states mere vanishing traces on the map. Here, as in many instances, the growth of the modern industrial world is exercising a controlling influence upon its political life. Mr. Webster, transcendent as he was in his ability in advocacy of the Union, was fortunate in that irresistible tendencies favored and reenforced his efforts for a united and progressive nationality.

"Two opposing factors have been at work in the development of our political institutions. The one is our magnificent isolation. It has been said that the Straits of Dover made England a manufacturing nation and gave direction to her growth in commerce and in wealth, because this narrow stretch of sea severed Great Britain from the continent of Europe and afforded protection from invading armies. How much more is it true that with a wide ocean on either side we are safe from immediate attack. It is not necessary that there should be frowning fortresses on the border. Our policy has been one of non-participation in the alliances or quarrels of Europe. This advantage in the upbuilding of our country, is worthy to be ranked with our boundless resources, with the spur of free institutions and the general prevalence of education.

"Over against this there is an opposing tendency, an inherited disposition for expansion. The predom- inant stock in the United States is descended from a nation which has been called the greatest "land-grabbing" people of the world. Sooner or later this disposition is sure to assume greater strength than today. Its manifestation has been retarded by the Wide extent of our territory which is open for exploitation but has not yet been utilized. The great increase in the use of tropical products, and the neglected wealth in the lands to the south have increased our interest in those localities, and the desire to annex them to the United States. Without entering upon an extended discussion of the subject, or expressing an opinion, it is a grave question whether a free people asserting the right of self-government should seek to say to another people, less intelligent. degraded even, "We can rule over you better than you can rule yourselves." The undertaking to acquire outlying islands, or dominion over other countries, would not only constitute a departure from fundamental ideas in American institutions, but is sure to powerfully react at home in the growth of centralizing tendencies and the greater toleration of arbitrary power. It is sure to be promoted, however, by theories which are now obtaining wide acceptance, to the effect that it is not only the privilege but the duty of more advanced nations to take possession of areas where disorder prevails or there is a low stage of civilization. This action is advocated even to the extent of urging the exclusion or extinction of the races now possessing these areas, and is based upon the theory of the survival of the fittest. The thought that all portions of the earth should belong to those who will utilize them is gaining an increasing number of advocates. It also is in line with contemporaneous events.

"The nations of Europe, some, of them at great loss and with poor success, are extending their colonial possessions and by diplomacy agreeing among themselves upon spheres of influence in which they may acquire new possessions from the uncivilized.

"But the most dangerous tendency in our political development is the growth of indifference, a tendency which after all threatens the very basis of good government. The result of boundless opportunities for the individual is that the most strenuous efforts are exerted for personal gain or advancement, and there is a neglect of the all-important duties which are of general concern, such as the orderly and efficient administration of public affairs, and participation in movements of general interest for the progressive advancement of society. In such environment as that which belongs to our citizenship, it will always be true that more rapid progress will be made in science and industry than in politics, because in these departments individual action has freer play and achievement is much more clearly in sight. In all governments there is a degree of inertia, proceeding from conservatism, from privileged classes or from those who gain special benefit from existing laws or institutions. All these cling tenaciously to existing conditions and although in the minority, often prevail against the general interest. According to the thought of many, a political career or political activity of any kind means hope without realization, labor without accomplishment, and devotion to duty without reward. This indifference is fraught with danger, it makes possible many evils. The great absorption in the development of our material life creates a commercial spirit which manifests itself in the idea that the vote of the people is like a commodity, to be controlled by money. It encourages those who have relations with the government to make its administration a means for personal profit. This last disposition has been especially noticeable in our municipal life. The boss has his beginnings in popular indifference and occasionally in the ignorance or gullibility of a large share of the electors. He could not, however, maintain his power, at least for more than a brief period, merely from the support of citizens who dwell in the slums of want and depravity, nor yet by the aid of those political henchmen in whose minds the whole framework of goverment exists for the sake of the fleshpots of office. His power is sustained in even greater measure by a class which assumes to be very respectable, men who desire franchises and privileges. These last are unwilling to waste their time in dealing with duly constituted authorities, such as mayors, boards of public works, and boards"of aldermen. They desire that their schemes should be subjected to the least possible amount of discussion or criticism, and hasten to accomplish their ends by asking, with callous disregard of rectitude, ' How much ,is it?' They desire to settle affairs with the boss with the same promptness with which they would arrange business transactions around a directors' table. If they were to be called to account, they would brazenly answer, 'Why, we are the truest representatives of the spirit of the times. We do business with promptness and efficiency.'

"Closely connected with these corrupting forces is the pressure of localities and special interests. This is particularly manifest in a time when great public improvements are being prosecuted. A great deal is said about the lobby and its demoralizing influence upon public men. The lobby does not originate in the legislature, but its pressure is brought to bear upon the latter's members, so that oftentimes they are impressed with the idea that if they do not obtain public buildings, appropriations for local benefit, or legislation for special interests, their best friends will be arrayed against them, or may be their whole constituency will demand their retirement on the ground of inefficiency. It requires the greatest courage for those to whom political responsibilities are entrusted, to stand for the general good in opposition to the more alert and oftentimes more intelligent activity of those who are prompted by nothing but selfish interests.

"Yet in the midst of some discouraging circumstances there is no reason for pessimism. We are not sot bad as we seem. Our extravagancies and follies are largely the result of our superabundant vitality and growth. There is hope that an awakening is upon us, under the influence of which the great forces which have made our national life so magnificent and inspiring may be restrained and directed solely in the paths of rectitude and peace. Dishonest wealth is no longer so honored as it was. Higher standards of honesty and of skill are demanded in both public and private affairs.

"The school, the college, and the church are doing their salutary work. Public opinion, the most despotic of all powers, is mightier today than ever. The newspaper and the magazine, though not always free from blame in their methods and teachings, are educating the masses as never before. If we can stay indifference and reach that ideal condition in which all of the most intelligent and upright shall take an active, eager interest in public affairs, we shall have a country not tarnished by graft or inisgovernment, or criticised as chiefly noted for the possession of material wealth ; but one in which, along with all that modern progress affords, and with the greatest prosperity, there will exist the highest standard of civic virtue and a republic which shall flourish like a plant of perennial bloom when kingdoms. and thrones have lost their power and diadems of gold have crumbled into dust. "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleONE HUNDRED AND THIRTY-EIGHTH COMMENCEMENT OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

August 1907 -

Article

ArticleTHE PRICE OF THE BEST

August 1907 -

Article

ArticleSOME CONTROLLING FORCES IN OUR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

August 1907 -

Article

ArticleBASEBALL

August 1907 -

Article

ArticleBASEBALL

August 1907 -

Article

ArticleSPEECH OF FRANK S. STREETER, ESQUIRE, PRESIDING AT THE ALUMNI DINNER, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 26

August 1907

Article

-

Article

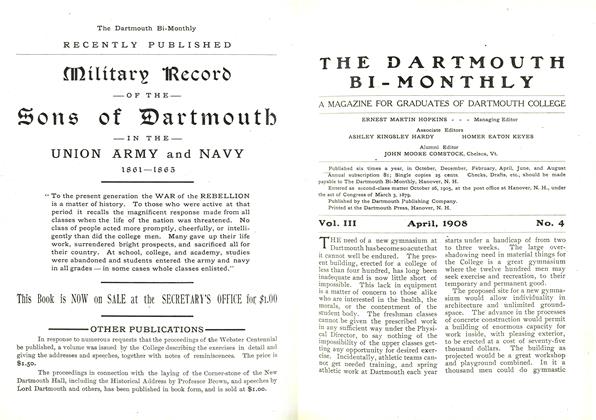

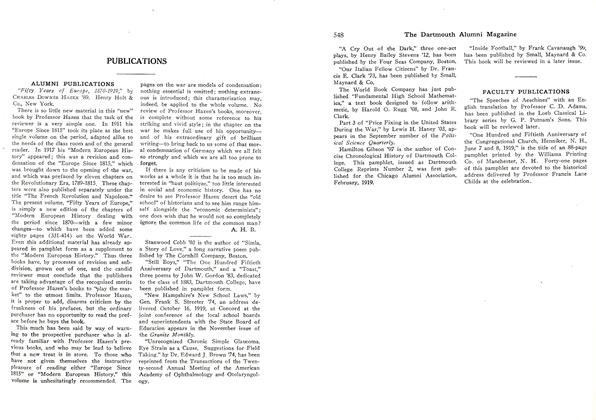

ArticleTHE need of a new gymnasium

APRIL, 1908 -

Article

ArticlePresident Emeritus Tucker in the Library of His Home on Occom Ridge

December, 1919 -

Article

ArticleAMERICA VS. ENGLAND

AUGUST 1929 -

Article

ArticleNewsletter Editor of the Year

JUNE 1970 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

DECEMBER • 1985 -

Article

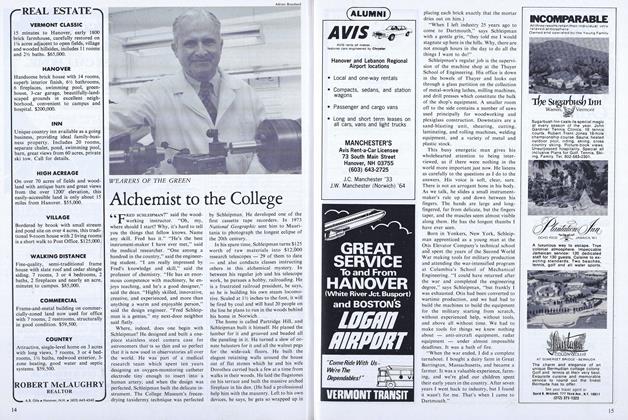

ArticleAlchemist to the College

APRIL 1978 By S.G.