John Stewart Kennedy died at his home in New York City on Sunday, October 31, 1909. In two months more he would have been eighty years of age. For almost three-quarters of that time he had lived in New York. He was born near Glasgow, in Scotland January 4, 1830, and came to this country in 1850 for the first time. Except for the four years from 1852 to 1856, tns home was here thenceforward. At the outset he was in the iron and metal trade, but he made his mark in business as a banker and railroad financier. For ten years—from 1857 to 1867—he was as- sociated with the late Morris K. Jesup, who was almost exactly of the same age, in the banking house oi Morris K. Jesup and Co., and in 1868 he established the firm of J. S. Kennedy and Co., of which he was the head until 1883. Then he retired, and the firm became J. Kennedy Tod and Co., Mr. Tod being Mr. Kennedy's nephew.

He became interested, in his early middle life, in railway development He was one of the incorporators of the Union Pacific Railway, one of the builders, and for some time a director in the Canadian Pacific, and had a share in the construction of what became the Great Northern Railway. At the time of his death he held directorships in a dozen other large banking and railway boards. In all these activities concentration, prompt decision, and energy, were mate with a wide view, sagacious foresight,and shrewd judgment in detail. He amassed a princely fortune, and commanded thv respect which, in a mercantile community, must always be entertained—not so much toward wealth as toward one who has shown his ability to gain wealth But the universal esteem for him had deeper grounds. He was known to be a man whose riches had been gained without swerving from the straight road of probity, whose moral principles were definite and unfaltering. He had taken advantage of great business opportunities. Natural forces and resources were pressing for development, and he had been on the spot, seen the possibilities, and taken them. But in doing it he had not crushed his rivals nor sacrificed his manhood. His business integrity was known to those who knew him, and teit by the community at large.

both money and unsparing personal service to the public causes in which he was interested.

He was a deeply religious man, and the promotion of religion made a strong appeal to him. In particular, the missionary enterprises of the Christian Church,— especially, though not at all exclusively, the Presbyterian Church, of which he was a member,— occupied much of his thought. The Presbyterian House in New York was advocated and brought to erection largely through his agency. Many opposed it at the time, but the wisdom of the building is now generally recognized. He was president of the American Bible House,— a great center of the printing and distribution of the Christian literature—in Constantinople. Missions and education united to constitute the strong appeal of Robert College, on the Bosphorus, to his mindr and in 1894 he became president of its Board of Directors.

It was with especial ardor that he threw himself into philanthropic enterprises. He was one of the founders of the Provident Loan Society, and one of its trustees, and a vice-president of the Society for the Ruptured and Crippled. On the ground of philanthropy and morals, both, he became a member of the "Committee of Fifteen," in 1901, under which the movement to suppress the evils of the "Red Light District" took shape in 1901. But his unique work of philanthropy was in connection with two great undertakings: the organization of public charities and the treatment of the sick poor.

He was well known among philar thropists as the president oi the Board of Managers of the Presbyterian Hospital. This post he held for the last quar ter of a century. It was no sinecure for him. He was a constant visitor at the hospital, whether at meetings of the Board of Managers and the Executive Committee, or for consultations with the superintendent, or for the personal examination of working details. Its policy was his constant care. His conception of it as a charitable institution never swerved. It found its expression in the inscription on the tablet attached to the corner tower at Madison Avenue and 70th Street:

"Presbyterian Hospital For the Poor of New York without regard to Race, Creed, or Color Supported by

His benefactions to it were frequent and large, but as far as possible so made as not to appropriate the hospital to himself as his personal affair, and discourage gifts from the general public. The great development of the Training School for Nurses connected with this hospital made a separate building for the nurses important, and this he supplied by the erection in 1901 of the Nurses' Home opposite the hospital in 71st street. It covers five city lots, and cost something more than $400,000. The anniversary meetings and other public gatherings connected with the hospital are held in its "Florence Nightingale Hall."

The growth of the territory between Central Park and Lexington Avenue, in the midst of which the hospital stands, as a residence district for the rich, led Mr. Kennedy to feel that the hospital is too far from the poorer population for whom it was primarily designed. A gift of $1,000,000 from him on the occasion of his golden wedding, in October, 1908, was soon followed by the securing of a large building site at 67th Street and the East River, and active steps will probably be taken soon to begin building operations there with a view to removing the hospital and Nurses' Home within a few years. This was his definite plan.

Mr. Kennedy's identification with the unifying of charitable work in New York began in 1891, when he erected the United Charities Building at 22d Street and Fourth Avenue. Four great societies are housed in it, at little or no cost to themselves: the Charity Organization Society, the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, the Children's Aid Society, and the New York City Mission and Tract Society. . Other societies with similar purposes occupy rooms in it at low rents,— any profit going to the societies for which it was built. In giving this building Mr. Kennedy wrote:

"It has long seemed to me important that some well-known charitable center should be established in the city of New York in which its various, benevolent institutions could have their headquarters, and to which all applicants for aid might apply, with assurance that their needs would be promptly and carefully considered." This was applying to charity in general the same principle of unification which the Presbyterian Building had embodied for the activities of that church. The results, in both, have been beyond expectation. Societies and boards have worked more intelligently, in greater harmony and at less expense, and those dependent on them have found approach to them greatly simplified. An esprit du corps in charitable work has been fostered, and the example set in New York is sure to be more and more followed elsewhere.

. But this is not all. Occupancy of the United Charities Building enabled the Charity Organization Society to carry out the plan of offering courses in the training of social workers. Mr. Kennedy gave permanence to these courses in 1904, by endowing "The" School of Philanthropy" with $250,000. He wrote in this connection:

"I obtained an act ot incorporation 101 the United Charities and erected the building which is known by that name, in the hope of securing thereby greater co-operation and more effective work among the important charitable agencies in New York, many of which are now located in the building. My expectations have been fully realized, and with then realization on the side of more efficient work has come a demand, not only in the city of New York, but throughout the country at large, for trained charity helpers. There is the same need foi knowledge and experience in relieving the complex disabilities of poverty that there is in relieving the mere ailments of the body, and the same process of evolution that has brought into our hospital service the trained physician and the trained nurse increasingly calls for the trained charity worker."

The courses of the School of Jrhilanthropy are now full to overflowing, and expansion is inevitable.

All the institutions which were the object of Mr. Kennedy's benevolence in his lifetime, and many more, including a number of colleges- in New England and the Middle West and in foreign lands, are beneficiaries under his remarkable will, by which half of his fortune of $60,000,000 is thus disposed of. Some of those he eared most for have a residuary interest as well. He left no children, and ample provision is made for Mrs. Kennedy and for all others who had a reasonable claim upon him. We, at Dartmouth, have reason to be grateful that, without any specific connection here, his discriminating judgment recognized the value of this College to sound education. The entire list, which follows, is an astonishing testimony to the wide vision, generous spirit, and staunch principles of the man:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Public Library, Columbia University and the Presbyterian Hospital each will come in for $2,250,000. A like amount will fall to each of three branches of activity of the Presbyterian Church, namely the Boards of Home and of Foreign Missions and the Church Erection Fund. The Church Extension Committee of the New York Presbytery will get $1,500,000, as will the United Charities and Robert College at Constantinople. The University of the City of New York the Bible Society and the School of Philanthropy of the Charity Organization Society each will receive $750,000.

The Presbyterian Board of Relief for Disabled Ministers and the Widows and Orphans of Deceased Ministers receives $30,000 to form part of the board's permanent fund and SIO,OOO to be applied to the Ministers' House at Perth Amboy. N. J. The Presbyterian Home for Aged Women in the city of New York in East Seventy-third street receives $10,000, and like sums go to the Board of Missions for Freedmen of the Presbyterian Church, to the Bible House of Constantinople, to the New York Bible Society, to the Young Men's Christian Association of the city of New York and to the Young Women's Christian Association of that city.

Next after the religious and charitable bequests come those to the educational foundations. Cooper Union gets $20,000; the National Academy of Design $20,000, the University of Glasgow, "where from my infancy I resided until I came to this country," $100,000, the Tuskegee Institute (Booker T. Washington's), $100,000, and the Syrian Protestant College at Beirut $25,000.

Seven of the country's colleges receive $100,000 each, namely Yale, Amherst, Williams, Dartmouth, Bowdoin, Hamilton, and the Hampton Normal School. Ten educational '.istitutions receive $50,000 each, these being Lafayette, Welles ley and Oberlin colleges, Barnard College and Teachers College in New York, Elmira College, Northfield Seminary, the Mount Hermon Boys' School at Gill, Mass., Anatolia College at Marsovan, Turkey, this latter bequest being made for the college to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and Berea College in Kentucky.

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions receives also $20,000 for the American School at Smyrna. Lake Forest University, Ill., and Centre College, Danville, Ky., each receive $25,000.

Coming to the medical and charitable institutions, Mr. Kennedy gives $25,000 to the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, "with which Miss Julia B. de Forest is officially connected," and $10,000 each to the New York Orthopedic Dispensary, the Home for Incurables at Fordham, the Manhattan Eye and Ear Hospital, the New York Society for the Relief of the Ruptured and Crippled, the Charity Organization Society, the Children's Aid Society, the State Charities Aid Association and the Alumnae Association of the Presbyterian Hospital.

The Bar Harbor Medical and Surgical Hospital gets $5,000 and the New York City Mission and Tract Society $20,000, St. Andrew's Society of the State of New York receives $20,000 as an addition to the permanent fund of the society.

Others will be led, it may be hoped, to follow Mr. Kennedy's example, but it will probably be long before this testament is surpassed, in the amount, the wide area, and the consistent purpose of its dispositions.

In private life Mr. Kennedy was genial and unassuming. His success, and his charities thrust him into the public eye, and he was in no sense a recluse, but ostentation he had no taste for. Modesty was his fundamental characteristic. His feelings were deep and his friendships loyal. He was a faithful church member, first of the Fifth Avenue, and in later years of the Madison Square Presbyterian Church. His own religious life was simple, frank and consistent. He never concealed it, and never made capital of it. Sturdiness of conviction marked him in this as in all things.

He was too pronounced a character not to have his likes and dislikes. He expressed them frankly, but without bitterness. His earnestness did not prevent him from appreciating humour, and he loved a joke. His quick speech, always sincere, never sarcastic, had often a touch of jovialty. He was an ardent sportsman, and especially a fisherman. Salmon-fishing was his delight. He was a member of two Canadian clubs, the Cascapedia and the Restigouche, and had long been president of the latter. He was equally fond of trout-fishing, and frequented the South Side Sportsmen's Club in Long Island, in the trout season. He loved the sea, and his summer home was near Bar Harbor. Wherever men met for rational pleasure he was a familiar figure, and many circles will miss his slight, erect form, his white hair, his straight, clear look, and his brisk vivacity of movement and of word It is a good life to have lived, and a good life to have known. The New York Evening Post, the day following his death, after speaking of his large charities. said:

Hewitt, Morris K. Jesup, John Crosby Brown, to cite only a few. They have been the great upbuilders of the city; their unblemished lives are the answer to the slander that the bulk of American business men are without scruples or patriotic devotion."

In life and in death Mr. Kennedy laid under obligation increasing thousands of persons whose names he could never hear. There is no way for any of them to repay the debt, except by living as wisely and faithfully and unselfishly as he.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Article

-

Article

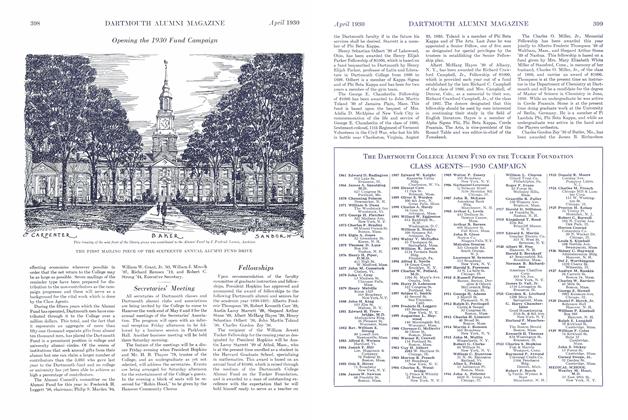

ArticleThe Dartmouth College Alumni Fund on The Tucker Foundation

APRIL 1930 -

Article

ArticleAN EXCELLENT CHOICE Editorial Comment

February 1934 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meets

December 1939 -

Article

ArticleBoston Supper

December 1941 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

May 1960 -

Article

ArticleTHE SPIRIT OF '21

December 1941 By George L. Frost