On this opening day of the one hundred and forty-second year of the College, we begin the forging of a new link on the forward end of the long chain of Dartmouth history. Responsibility lies upon each one of us to go about his work soberly and thoughtfully to the end that the College may grow in strength and worth as it grows in years.

Every young man who comes to College of his own wish must have somewhere in his mind the idea that the training and discipline of the College can do something for him which he cannot well do by himself. The result of college opportunities, which he clearly or vaguely forecasts, must be a large and far reaching result else it would not be worth giving four years of his active life to gain it.

To you, therefore, the question— what is a college for?—is a vital question. It is a matter which touches your deepest interests.

Let us begin at some distance from the point by clearing away a few of the numerous misapprehensions about college and college life.

It is often,said that college life is a narrow life, and that the man who goes out from college into the world must promptly broaden his mental horizon. In reality just the contrary is oftener true. The difficulty encountered by most college men, on entering the struggle for a livelihood, is just the opposite "one. The man must narrow his mind to a cutting edge which will work intensely along a thin groove.- During the hours of his labor he must cramp his thoughts within the close limits set by the details of his business or profession and resign himself to thinking of nothing beyond them until the end of the day.

The world, as a whole, is broader than the college, for it contains the college and much beside, but no man at graduation or later earns his living in the world as a whole but only in a special part of it— a far more specialized part of it than that represented by the college. The pains suffered in the transition are not growing pains but cramps. It is a passage from freedom into an eight hour a day bondage. The process is not one of expansion, but of mental contraction to the point of ferocity. It is not a question of pulling himself up to a broader level of intellectual attainment but of making the best terms he can with necessity on a plane where the aim is intensity rather than breadth.

Again we often hear that when a man leaves college he must learn what work is. We must freely admit the truth of this for the college men who lack the power of self-directed effort, or fail to realize a man's just responsibility to his work. Such men are content with the easy effort which gains a passing mark, at present set too low for men of average ability who can command their whole time.

For the man who believes in what the college can do for him, who has developed a sense of responsibility and has confidence in his powers and delights to use them, the case is quite otherwise. For him the passing mark has neither significance nor dread. He is willing, if need be, to sacrifice the temporary for the permanent, and tries to the utmost of his capacity to realize broadmindedly in himself the intellectual and moral ideals for which the college stands.

The world outside, when he enters it, will ask no more of him than he has freely given to the college. He will not need to learn of it, either the meaning or the fruits of steady, careful, and consistent effort.

The aim of the college is not to teach faultfinding. Stimulation to original and productive effort is more its purpose than the training of critics. Early manhood is the natural period of greatest creative energy, but an atmosphere of destructive criticism in which small flaws appear larger than great achievements paralyses self expression. It forms the pessimist who shrinks more from two discords in a masterpiece than he expands under the harmonies of a great symphony.

Creative thought and effort like all natural processes are prodigally wasteful and produce much useless timber which must be cut away from the living growth. Men in college should be taught that discriminative judgment which easily separates the useful from the useless, the genuine from the spurious, sanity from sensationalism, but balance must be kept and a generous admiration and enthusiasm for the power and inspiration of a large minded work alone can justify dissatisfaction with its minor details.

The man whose well is dry, or who is too lazy to draw from it, is often tempted to a small if unconscious revenge in seeking flaws in the work of others. He is apt to speak patronizingly of his more energetic contemporaries and condescendingly of the ancients. His part in life is negative, not positive: he knows subtraction but not addition.

Men in college, where more than anywhere else each is his brother's keeper, should watch themselves and one another for the first signs of this mental decay. It often starts from nothing larger than a mild discontent with vigorous effort. It is so much easier to study surfaces than substance, to acquire manners than morals, to make light sentences than to explore thought.

Such mental'and moral shirking saps intellectual vigor as physical laziness atrophies muscle. The physical sluggard who sneers at the athlete finds small favor in college. So also should his parallel, the mental do-nothing who speaks condescendingly of intellectual prowess and scholarship.

The purpose of the college is not to teach men how to make money. On the contrary let us hope its moral discipline will actually prevent college men from making money in ways which, though not tangibly illegal are yet palpably unrighteous. Its effort is to train men for effective service, be the price of that service what it may.

College training can do yet a better thing than to teach men specifically how to make money. It can teach them how to spend it. It can teach the worthy and unworthy uses of money.

Ten men know how to make money, to one who knows how to spend it. Our country, and all other countries, today are in greater need of a more widespread wisdom in the spending of money than of shrewdness in getting it. Money represents power, and the thirst for power is rudimentary and instinctive. The wise use of power on the contrary is an art, the practice of which requires the higest moral purpose, integrity, and mental cultivation. Power in itself is without moral quality, it may accomplish good or evil, which, depends upon him who wields it. The right use of power is a sacred obligation upon him who has it.

A trained intellect is the surest instrument with which to gain power but an equally trained moral sense must be added,. to realize its nobler possibilities. Mankind has suffered more from the ignorant and unprincipled exercise of power than from most of the questionable methods employed in acquiring it.

College brings young men together at an age when physical and mental activity are both approaching the highest stage. The roots of character are settling into the deeper ground from which in later years the fullgrown man will draw his sustenance. The college aims to bring men together in a generous and manly comradeship where there is friendly rivalry but the prizes sought are unselfish. There is nothing sordid in them; none seeks an unworthy advantage over another; victory finds applause and earnest effort wins respect.

Every man now in college whose eyes are open to the present and the past (and it is the purpose of the college so to open men's eyes), every man who thoughtfully compares the world's life of today with the life his father met when he first came face to face with it, thirty years or more ago, must realize some of the significant changes that have taken place. Mastery of the tools employed to earn a livelihood has become more difficult, for these tools are more highly specialized, their number greater, their uses more diverse than a generation ago.

The social order and the state are facing new and far more complex problems than ever before. The need of men in private and public service who have highly trained minds, minds disciplined in the keenest analysis, men possessed of spiritual poise and insight, was never so pressing as now. More men who can intelligently and safely bear the gravest responsibilities, more men of trained judgment, foresight, and unswerving ideals of justice must be forthcoming or society and the state will soon come to confusion.

When you leave Dartmouth you will meet the world at a critical stage in its history and I ask you to prepare yourselves thoroughly here and now for the service which will be required of you. All the store of wisdom, spiritual experience, and intimate knowledge of men and nature, which the world has patiently gathered, is not too full an equipment with which to face tomorrow and its perplexities. As much of this great heritage as four years can cover, the College now offers you and at the same time opens the door to the rest.

The purpose of the College, then, is to prepare men for life, the life of their own day, to teach them to see life in its larger and more lasting significance, 'to see it steadily and to see it whole.' To make the mind a trained instrument in the firm grasp of a steadfast will, which is in the spirit, and to quicken the spirit through the understanding is its larger task.

On its moral side life needs not new ideals, but a more unfaltering fidelity to older ones. The surroundings in which we live have become so intricate that the good and evil in them are hard to separate. Temptation to accept the lesser good both in private and public affairs, was never keener, nor more shrewdly masked. Man now more than ever before needs for his strengthening and his guidance, broad acquaintance with the long records of conquest through which man has sought his own soul. He needs to be keenly alive to the best that has been thought and said and done in the world. He needs to know the slow steps by which man, with true science, has found out natural law and is establishing a firmer control over his environment, not by breaking law, but by obeying it. "Hitch your wagon to a star," says Emerson, "not until you know the star is going your way," adds science, "for your will is powerless to change the law of its motion."

The College strives to interpret mankind to man, to unravel nature, to seek out God. It exists that men may have life and have it more abundantly: it seeks not to destroy, but to fulfill.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFollowing the resignation of Ernest Martins Hopkins

November 1910 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Changes

November 1910 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH CLUB OF BOSTON*

November 1910 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

November 1910 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1845

November 1910 -

Article

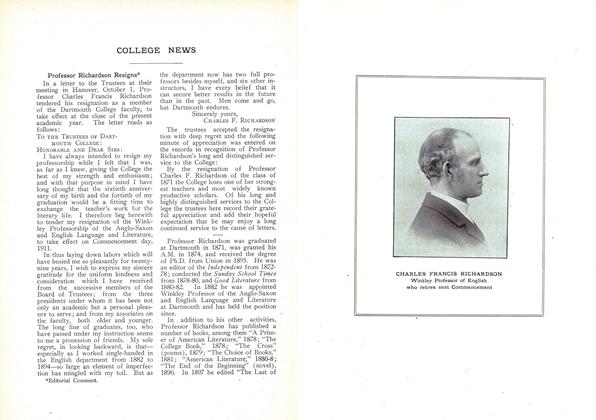

ArticleProfessor Richardson Resigns*

November 1910