(The ALUMNI MAGAZINE publishes with pleasure communications from its subscribers, but assumes no responsibility for opinions expressed.)

EDITOR ALUMNI MAGAZINE:

The poems of Richard Hovey possess so much interest that the following specimen of his juvenilia may: be interesting to your readers, especially as it concerns Dartmouth. When the class of '85 went to Montreal, February 22, 1882, for its freshman class supper, Richard Hovey was, of course, chosen to write the class song. It was printed in the dinner menu, and has not, so far as I am aware, ever been seen in print since until a few days ago. The words had lingered for a quarter of a century in the memory of his classmates, two of whom were able to recall the first and last stanzas and hand them on the children of '85 at a family picnic during the 25th reunion. Rediscovered in their entirety in an old college scrapbook of the class secretary they were reprinted and sung by two generations at class headquarters, on the campus, and at the alumni dinner.

It was written by Hovey when he was a Freshman, not yet eighteen years old.

Sincerely yours,

THE CLASS OF '85

BY RICHARD HOVEY

AIR—"It was my last Cigar" Anacreon sang of love and wine, And Pindar sang of horses, And Homer struck his harp divine To celebrate war's courses, Tyrtæsus, with his brands of song, Fired Spartan hearts to strive; But ours the greatest theme—we sing The class of '85.

CHO.—The class of '85, The class of '85, But ours the greatest theme—we sing The class of '85.

We're not averse, we own, to sport, And not in love with work; It's a cold day when we labor If we have a chance to shirk, Yet for our Alma Mater's honor We will always stoutly strive, And sing the praise of Dartmouth, And the class of '85.

CHO.—The class of '85, The class of '85, We'll sing the praise of Dartmouth And the class of '85.

Like Eastern princes banqueting, We feast at learning's board, Where wisdom's meat is placed to eat, And the wine of wit is poured; And when, as come it must, the hour Of parting shall arrive, Our last toast shall be And the class of '85."

CHO.—The class of '85, The class of '85, Our last toast shall be "Dartmouth And the class of '85."

And when our youth has taken wing, And like a dream has fled, And the hairs are thicker on each face, And thinner on each head, And children swarm about our knees, Like bees about a hive, Our thoughts will turn to Dartmouth And the class of '85.

CHO.—The class, of '85, The class of '85, Our thoughts will turn to Dartmouth And the class of '85.

EDITOR OF THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE:

An article in the last MAGAZINE has struck me, but I can not say that it gives me pleasure. I refer to the article, "Fraternities and Scholarship." It seems to me that the average scholarship in Dartmouth is mighty low, and that this low standard of scholarship should be investigated, and the causes, if any, ascertained. The following questions occur to me: Is the preparation of the pupil less than in the days when some of us entered Dartmouth College? Is this inferior preparation, if it is such, due to the unlholy demands made upon the preparatory schools by young and inexperienced college teachers, who have in mind a wide preparation on the part of the student entering, which will make unnecessary the old-fashioned drill work that many of us received in our freshman year? Is the method of teaching now pursued by the college professor faulty? Is there not too much of what the Indians call "heap cheap talk," which lacks so much of definiteness that there is never before the student a clear, definite task' which he can assail with the knowledge that he is getting what will be demanded in the recitation? It is my observation that the lectures of these young chaps are rambling, not getting down to the very kernel of things, lacking originality, consisting largely of a little from this textbook, and a little from that textbook, delivered in such a dull, uninteresting way that the average pupil will go to sleep under such soporific doses, so that a majority have nothing to go by after the recitation except the notes of a few grinds, whose zeal for marks, rather than for learning, causes them to take down notes.

Is it not true that these same college professors, who ramble around, and are so indefinite, and never assign' definite tasks to their pupils, in their examinations, on the contrary, demand certain definite knowledge which in the very nature of things the students are unable to show ?

Is not the wide elective system, which permits pupils to take a little of that and a little of the other, as their fancy may dictate, also in a measure responsible? Would it not be better to reconstruct the course at Dartmouth College, so that there might be five or six definite courses from which a pupil could choose a course best suited to his needs? This series of courses could be improved from year to year, until finally they would be so arranged that each one represented very nearly the same amount of effort, and would produce the same degree of scholarship. Would not such a series of courses be a boon to the boys themselves, and a satisfaction to parents who are unable to advise their sons, and would it not be a very wise restraint upon students who may have in mind an easy course, rather than one that will do them the greatest amount of good ?

Referring again to the financial part, would it not be a great saving to the College to have the students in groups, after the manner suggested, and would it not be stimulating to have a larger number of students working along the same lines ?

I hope you will overlook my butting in on this matter, which I can not help thinking exceedingly important

I believe the American colleges are making foolish and unreasonable demands upon our high schools and academies, that they are lowering rapidly the standard of scholarship, that our young people are getting into the habit of frittering along, and taking a little of this and a little of that, which is not only calculated to make poor scholars, but which will affect unfavorably their character and their method of approaching the serious things of life.

If the old plan of scholarship did no more, it did assign certain definite tasks. The fellow who knew absolutely what was required of him, with no mistake about it, knew that if he did not come up to the dough-dish it was his own fault. Today, however faithful the pupil may be, he is groping his way most of the time in the dark, not knowing really what the teacher is expecting, a most unfortunate condition.

I could say a great deal more along this line, but I believe I have said enough.

ALUMNUS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe one hundredth and forty-first

June 1910 -

Article

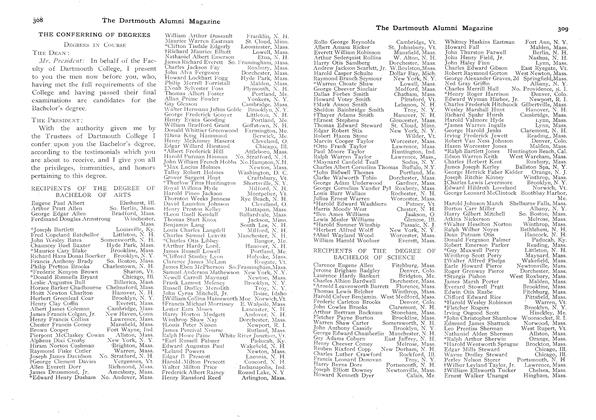

ArticleTHE CONFERRING OF DEGREES

June 1910 By Frederick C. Allen, -

Article

ArticleSAMUEL PENNIMAN LEEDS

June 1910 By William Jewett Tucker -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS' ADDRESS AT COMMENCEMENT VESPERS

June 1910 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

June 1910 -

Article

ArticleSPEECH IN BEHALF OF THE CLASS OF 1911, ON RECEIVING THE SENIOR FENCE

June 1910 By Harry Butler '11