The immediate feeling following upon the death of Doctor Leeds is that of thankfulness for his old age. No one who remembered him as he was when he came to Hanover in 1860 expected that he would live to be eighty-six, and yet all who knew him in these later years were surprised when told of his approaching death. We simply missed him for a few days from the street, and he was gone. He seemed to have acquired, as he went on, the habit of living. Having outlived the early anxieties of his friends, having thoroughly mastered the climate of Hanover, and having made the memorable record of forty years in a college pulpit, he entered, as entitled according to the academic phrase, upon "all the rights, privileges and immunities" of age. The charm of it all was that he continued to grow. He met the new, whatever it might be, with an open mind—new men, new ideas, new problems and opportunities.

The graduates of a college are apt to think of a college community as overstocked with old men. When I came to Dartmouth in 1893 the oldest man on the faculty was fifty-seven, three others were in the early fifties, the remainder were under forty-five. The one thing at that time in our College community of which we were scant was age, except as President Bartlett gave us in his retirement a delightful example of its dignity, good cheer, and activities. The distinction of Doctor Leeds lay in the continuity of his service. His life bound together five chapters in the history of the College, reckoning by administrations—the closing years of the administration of Doctor Lord, the entire administrations of Doctor Smith, Doctor Bartlett, and myself; and he lived to welcome Doctor

Nichols to the succession. It would be a matter of no little interest to know what he really thought as with his shrewd, quaint, and humorous sense he watched this succession of men and events. Whenever he chanced to speak of his "Reminiscences" I strongly urged him to withhold nothing of his inner thought, but I fear that his pages do not reach far into recent times. Doctor Leeds was, however, far more than an interested spectator. He was an invaluable part of each administration. Ten generations of Dartmouth students are witnesses to his earnest, sympathetic, and stimulating ministry. Whether they fully realized the fact or not, he carried every student on his mind and heart. The spiritual power of the College was his great concern. He felt at all times the power of the College: what he longed to accomplish was the appropriation and diversion of a larger part of that power to the highest ends of human service. In his letter of resignation he declares what his purpose had been in these words:

"I am not wont to note any but superficial faults in the sons of Dartmouth,— and what energy and perseverance and generosity have I not seen among them! But I ask myself sometimes whether in the long, necessary, and most arduous struggle of life- they may not form the habit of seeking great things for themselves, and fail to form the habit of selfsacrificing service. Yet many, yes, very many have I known here in college and outside of college, in obscure life as well as in high places, who have sought great things for their Lord and their fellowmen, and who in the final day shall be 'found unto praise and honor and glory.'

"Let us attempt the best things possible to us. And let us not define 'the possible' too narrowly. If my life has taught me anything, I had almost said, it has taught me that lesson. I believe but few very important-things have been done in the world which have not been declared impossible beforehand, and often by thoughtful people."

Doctor Leeds was a New Englander by a single remove, but that remove was sufficient to modify his temperament, his outlook on men and affairs, and his ways of thinking. Born, and bred in the city of New York, when the city was small enough to be accessible in every part to an active boy, he took a lasting impression from his boyhood surroundings. The house in which he was born stood on the corner of Wall street and Broadway. The Battery was his playground. The historic sites were all familiar to him. He could never quite endure his father's pride as a Bostonian. Bunker Hill had no claim upon him above Washington Heights. In the midst of these early surroundings he saw much of the young civic life of the country — the visits of the Presidents, pro- cessions and celebrations, political campaigns, and the coming and going of distinguished men from abroad. Later he "went to college" at the University of New York from which he graduated in 1843, and upon graduation entered Union" Theological Seminary for the three years professional course for the ministry. The three men who had 'the greatest influence upon him during this earlier period were Theodore Frelinghuysen, Chancellor of the University of New York, Edward Robinson, the greatest American biblical scholar of the time, then a member of the faculty of Union Seminary, and later Albert Barnes of Philadelphia, with whom he served as assistant minister. These were all men of marked liberality of mind, and of equal devotion to duty. The whole atmosphere in which he grew as a boy, in which he was educated, and in which he began his professional work at once stimulated and tempered his mind. Unconsciously perhaps, but none the less surely he became broadminded, hospitable, tolerant, a man of deep conviction, both in doctrine and in morals, especially in respect to the then rising question of slavery, but a man able to discriminate between the permanent and the transient in the hour of controversy. His training fitted him to become a steadfast upholder of the truth, and a steadfast champion of the right, but not to become a sectarian or a partisan.

It was of advantage that a man of this training, at one remove from the more controversial temper of the New England mind, should come to the college pulpit at Hanover when controversies, political, scientific, and theological were impending. New England had a full suply of controversialists. She could well afford to borrow an ally and helper from a somewhat different school of intellectual activity and conflict. How well Doctor Leeds met the requirements of his position is attested by the calm judgment of his contemporaries as they reviewed his ministry at its close:

"In a church and community marked by very divergent opinions, strongly held and openly expressed, on religious, social, and political subjects, he has maintained his independence without compromise, and without offence, and bringing no reproach upon the cause of Christ, has exhibited to all an unselfish gentleness."

The character of Doctor Leeds, his personal characteristics, his whole personality grew richer, more enjoyable, more lovable under the intimacies of friendship. Doctor Leeds did not belong to the aggressively compelling order of men either in public address or in conversation. He had the spirit of the orator, .as one might often see who watched him under the kindling of imagination and feeling, but he lacked the full .power of physical expression. More of this spirit came out in conversation when it was easy for him. to get an immediate and interested hearing through his fund of information, his ready speech, and his natural wit. But the essential characteristics of the man were at all times in evidence among his friends. No one whom I have heard speak of him in public or private since his death has failed to note his sense of humor. It was very quaint. Often in the flow of serious talk some little aside would interrupt but not hinder the thought. His anecdotes and stories were always illustrative, and never rambling or prolix. In his letters one constantly met with delightful surprises of thought or style, a happy turn, a fresh word, a side look. Not much of his humor was quotable, it was so interwoven in his style: it was simply his way of thinking and of expressing himself in the freedom of conversation or corres pondence.

A characteristic, less noticeable but at times quite effective, was his shrewd wisdom. Doctor Leeds was both a well read and a well informed man. He read books, he read the papers, he read men. His observations on current events were as wise as his criticisms of public men were acute. He was seldom mistaken in his opinions or estimates These were not mere intuitions but the result of long and patient observation, comparison and study. He knew how to think of men individually and also as affected "by the groups and classes to which they belonged. I once heard him say quietly after listening with some impatience to a superficial harangue on the impracticability of ministers: "I have noticed that by far "the largest per cent of actual failures in life is to be found among business men."

Among these minor characteristics of Doctor Leeds was his discriminating habit of mind. He was not a man to be imposed upon intellectually. Hospitable as his mind was to all new thought, he was never deceived by any kind of sophistry. His perfect confidence in the truth did not blind him to the dangers of error. He passed through many so called "crises" of faith, but he never lost his intellectual or moral poise. If error had its dangers he saw better than most men its inevitable fate. His insight and forsight saved him from the retreat which many men of his time "were obliged to make from untenable positions. One reason why his intellectual life was steadily progressive and cumulative was that he had so little to take back. Courageously hospitable as he was in his openness of mind, he never allowed himelf to be imposed upon by his guests.

But the characteristic of Doctor Leeds which really gathered up into itself the whole of his enlarging life, was that he was a great Christian. Rooted in Christianity he grew that way. His virtues were the Christian virtues—towards men, good will, a charity active, generous and far reaching: toward God, humility, assured confidence, and love: and toward the Kingdom of God, loyalty, courage, and an unconquerable hope. All these were in him and abounded, and being in him and abounding, the promise was fulfilled that he should "neither be barren nor unfruitful," He died in the fulness of his spiritual life. His lamp did not flicker: it was quenched in full flame.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe one hundredth and forty-first

June 1910 -

Article

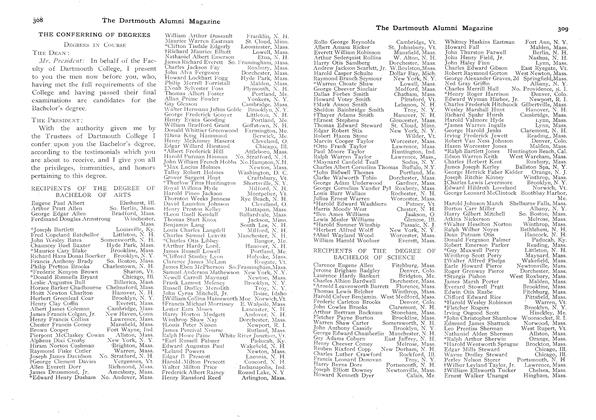

ArticleTHE CONFERRING OF DEGREES

June 1910 By Frederick C. Allen, -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS' ADDRESS AT COMMENCEMENT VESPERS

June 1910 -

Class Notes

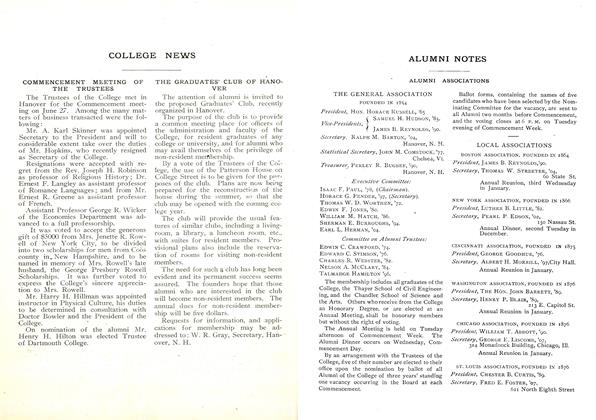

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

June 1910 -

Article

ArticleSPEECH IN BEHALF OF THE CLASS OF 1911, ON RECEIVING THE SENIOR FENCE

June 1910 By Harry Butler '11 -

Class Notes

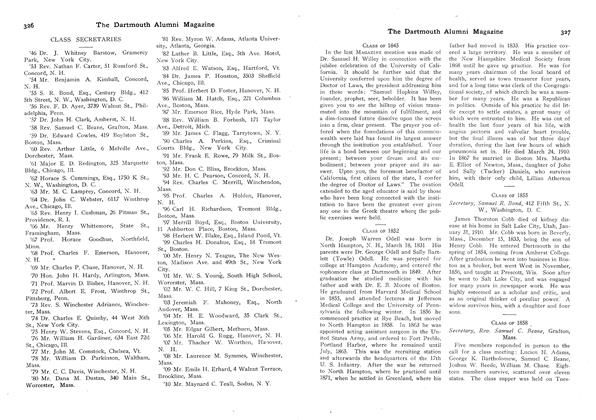

Class NotesCLASS OF 1860

June 1910 By Arthur Little