Some years ago, Dr. A. G. Brush of Fairfax, Vt., sent to the "Professor of the College" a neat little home-made book of notes, with the statement that if he—the Professor—did not care for it he could give it away to any one that he pleased.

He cared for it, though inactively; for while the handwriting was Well-formed the ink had faded too much for easy reading. But recently the whole has been copied into about forty type-written letter pages, and the contents are revealed.

The book contains notes upon the

"CHEMICAL LECTURES

As delivered in a Course of Lectures at Dartmouth College, Oct. 1st, A. D., 1806, by NATHAN SMITH, M.D., Professor of Chemistry."

William C. Ellsworth of Bristol, Vt., one of the forty-five students at Dartmouth Medical Theater, that autumn took these notes, seemingly very well. Some are so good that they, argue copies from a written form; while others, it is true, contain certain incoherencies like those of which the moderns sometimes say, "Well, that is the way I have it in my notes, anyway."

Dr. Smith's lectures, while perhaps falling a little short of the scientific accuracy and professional limitation of the Syllabus of his predecessor, Lyman Spalding (1798-1800), show that for a busy doctor, and for a teacher with the obligation of omniscience, he was pretty well informed upon the new science.

Eighteen hundred and six was only twelve years after the death of Lavoisier. Not yet for at least two years was Dalton's Atomic Theory made public. Berzelius's notation had not been suggested. Chlorine, that active "hooligan", as Dr. Dixon, President of the British Chemical Society, says his lady pupil called it, had been discovered by Scheele, but was still considered a compound—oxy-muriatic acid. So the little book is artlessly constructed without any chemical symbols or formulas or atomic weights, but not without modern nomenclature, and occasional statements of weight relations which are usually incorrect.

The allowable space for a relic of this kind is better used for the matter than the literary style of a student's notes; but it is a joy to observe in passing that "gass" and "seperate" were the same gay deceivers then as now; the thought gives a home-like feeling to that century-distant college world.

And the frequent use of cum, sed,sine, and vel, as often in the fair, apparently verbatim, copy as in the student's abstract, suggests an eccentric affectation of the lecturer; is it a survival of rudimentary Latin from the university lecture ?

Dr. Smith taught by experimental demonstration which his disciple faithfully set down. The first experiment, instructive though unexciting, was, "Put a quantity of Chalk with Water and No action ensues." But the chalk soon had a chance to show what it could do with acids. And in general, chemicals once assembled fizzed, flashed, and banged just as they do now, no matter under what theory, or guise of explanatory language; and it is even noted that oxygenated muriatic acid gas, which we now call chlorine, "Excites a Violent Cough."

The topics of these lectures were, in their order,

Chemistry, Nature and Laws, Caloric, Melting and Boiling Points, Iron and preparations, Cuprum, Silver, Gold, Water, Heat and Light, Gases, Oxygen gas, Hydrogen gas, Azote or Nitrogen gas, Carbonic acid gas, Sulphurated hydrogen gas, Carbonated hydrogen gas, Oxygenated muriatic acid gas, nitrous gas, ammoniacal gas, sulphurous acid gas, muriatic acid gas, fluor acid gas, sulphur, carbon, arsenic, mercury, phosphorus, lead, tin, zinc.

The treatment was unsystematic, and ran largely to therapeutics.

A few citations show the point of view, which has its contrasts and its resemblances to ours.

"Chemistry differs from Mechanics in the uncertainty of the effect from the force applied", or a big detonation may ensue from a little percussion.

"Law 3rd. The affinity of composition is in inverse ratio of the Affinity of Aggregation", which seems to mean that solids do not react so well as the same substances in solution.

"Law 7th. Bodies have different degrees of attraction for each other which are to be ascertained by the difficulty of destroying the combination between two or more bodies."

"Law 9th. The affinity of Composition of Different bodies is modified in proportion to the Ponderable quantities of the substances placed within their spheres", which sounds like an early statement of Mass Action.

"Caloric. Much altercation has taken place among philosophers cum regard to the Nature of Heat. Some contend that it is a substance, while others that it is only a quality or peculiar modification of matter. Many very plausible arguments are adduced in support of the former, while many no less flattering are advanced to prove the latter."

"Caloric is an imponderable substance which penetrates all bodies."

"But the opinion that heat is a distinct elementary substance will better account for the different phenomena that take place in bodies."

"Light appears to be a substance emanating in right lines from all luminous bodies."

"Gas is an Elastic, Aeroform, Transparent, Ponderous, Invisible Fluid"—it must have been worth while to lecture in those days of mouth-filling vocabularies— "not condensible by the most intense cold into the fluid or solid state", —a distinction that has forever vanished.

"All the gases are compound bodies consisting of some substance combined cum Caloric or Light",—perhaps the idea does not differ so much from ours as the mode of statement.

"Water is an inodorous, colorless, insipid, and incompressible fluid",—another orotund characterization—; "it is not an element as the Ancients supposed, but a compound of oxygen, hydrogen, and Caloric." Whatever the case for Caloric, it was only twenty-three years since Cavendish's experiment had demonstrated the compound nature of water.

Some words are used which savor of the alchemical ages, as pompholix, lapis infernalis and virgin's breath; and some statements surely come from the days when chemistry was the Black Art and its practitioners were in danger from an irate populace. For instance, we cannot support the ghoulish announcement that "hydrogen sometimes is produced in the Stomachs of People and issuing from the Mouth takes Fire and kills the Patient if put in contact cum a Blaze", though we should like to use it as a Warning to Cigarette Smokers.

Dr. Smith has some observations of his own; he notices that Ammoniacal gas will penetrate those substances that are impenetrable to other gases. "This circumstance I do not remember to have heard of before, and with me it was merely accidental while endeavoring to enclose this gas in a bladder."

He also describes a case of convulsions which he ascribes to the external use of an ointment containing lead, and which, he tells the boys, he cured by stopping the lead and using alum.

He shows himself to be a practical chemist "in the case of some children who lost entirely the use of their limbs from taking Dr. Rawson's Worm Powders." For he assayed a sample of the powder and obtained a button of tin, which was not good for the children, at any rate.

Inbound with the Chemistry notes is Dr. Smith's "Farewell Charge" to the Medical Class of 1806, in which we find, "You have not Finished your Studies; you have only laid a foundation for them, on which to build must be the business of your future lives",—the fundamental thought of every subsequent farewell address to medical classes; and "Improve and perpetuate what has been so happily begun by the present Generation. We commit their unfinished labors to your care, and while we are descending into the Vale of Life we shall be consoled in reflecting that the science we have loved and taught will be improved by your hands more than it has been in ours",—a thought as pertinent now as then.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ALUMNI ALCOVE IN THE COLLEGE LIBRARY

March 1911 By Eugene Francis Clark '01 -

Article

ArticleMost of us have been vaguely aware of the existence of something known as the "alumni alcove" in the College Library.

March 1911 -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

March 1911 -

Article

ArticlePresident Nichols Addresses Students

March 1911 -

Article

ArticleConcerning the Agora

March 1911 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS SECRETARIES

March 1911

Edwin J. Bartlett

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorALUMNI OPINION

January, 1911 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleTHE CHEMICAL LABORATORY

By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Books

Books"Portraits of a Half Century"

January, 1926 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

ArticleThe Vicissitudes of South Hall

APRIL 1929 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

ArticleThe College

September 1976 By Edwin J. Bartlett

Article

-

Article

ArticleDPA Pioneers Are Home

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Article

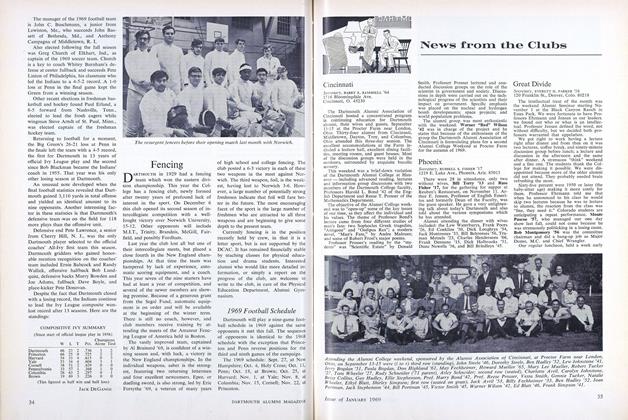

Article1969 Football Schedule

JANUARY 1969 -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

SEPTEMBER 1989 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

NOVEMBER 1990 By E. Wheelock -

Article

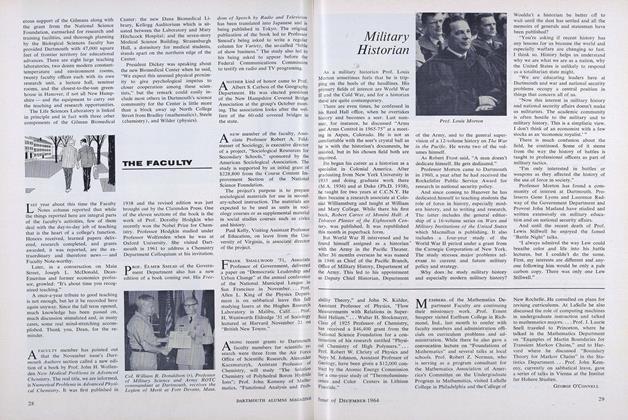

ArticleTHE FACULTY

DECEMBER 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleWestern Washington

October 1973 By LAWRENCE B. BAILEY '63