Charles Darwin Adams: Demosthenes and His Influence

AUGUST, 1927 William Stuart Messer, Edwin J. BartlettCharles Darwin Adams: Demosthenes and His Influence William Stuart Messer, Edwin J. Bartlett AUGUST, 1927

Longmans, Green and Co., New York, 1927.

It is fitting that an alumnus of the college of Webster and of Choate should have made of Greek oratory his special field of study. It is even more fitting that the above book should appear just at the time when this alumnus is about to retire after nearly a half century of inspiring teaching. Professor Adams, while shirking none of the onerous demands of committee work and of instruction, has yet found time to carry on the researches of a scholar. Among English speaking classicists and on the Continent he has won the position of a recognized authority in his chosen field and, in so doing, he has brought honor to his alma mater.

Three books have grown out of these studies: the Lysias, appearing in 1905, the Aeschines in 1919, and now the Demosthenes. The Demosthenes is the most recent addition to the series Our Debt to Greece and Rome, each volume of which is written by a specialist in the subject of his essay. The effort to secure the necessary balance between the minutiae of research and the larger treatment, imperative in a series addressed to a popular audience, has produced in too many cases merely a combination of irrelevant erudition and cumbersome attempts at the lighter touch. On this head the volume before us is above criticism. No reader can fail to realize that the author is writing out of a profound store of knowledge; but he avoids pedantry and his popularization is dignified and well proportioned.

The book outlines in 180 short pages the facts of Demosthenes' life, explains the technique of his oratorical art and, lastly, traces his influence through classical antiquity down to the present.

Throughout the ages the statesmanship of Demosthenes has been alternately praised and belittled. Recently we have been passing through one of the latter phases. Toward the close of the nineteenth century his reputation suffered an eclipse. German scholars, our masters in the sphere of ancient history, likening Prussia to Macedon, and enjoying the security and power of German unity under that leadership, denied Demosthenes all political sagacity and even discredited his integrity. This ill repute it is Mr. Adams' task to consider. In a chapter of rapid, concise, vivid narration he summarizes the situation in Greece from the rise of Macedonian power in the north to the total enslavement of Athens on the death of Alexander. In language all the more convincing because of its sobriety, its moderation, its lack of unwise eulogy, these pages retell the story of the heroic efforts of Demosthenes against the enemy abroad and the traitor at home, mounting to a climax in the greatest lawsuit of all history—the contest of Demosthenes and his rival orator Aeschines "On the Crown." Demosthenes, far from being guilty of the charge of a chauvinistic and fanatical opposition to a beneficial Macedonian leadership of Greece, as the Germans maintain, failed, if at all, in not being able to see the depths of disgrace to which Macedonian supremacy was to plunge the free states of Hellas. Just one generation after the warnings of Demosthenes the Macedonian king Demetrius did Athens the honor of graciously adopting deification, and for one winter made the Parthenon the banquet hall and bed chamber of himself and the notorious courtesan Lamia. Mr. Adams' defence of Demosthenes is very persuasive and the reader will accept or reject it according to his political beliefs. As a short historical sketch of this period the chapter is unexcelled.

The section on the oratory of Demosthenes is not predominantly technical, though those who wish to read a simplified account of the orator's technique will find it as clearly defined there as it can be for those who can not read Greek and who are unfamiliar with ancient rhetoric. It is rather the broader aspects of Demosthenes' problems and his methods of meeting them which are described. His speeches were delivered to persuade and had to be adapted to his hearers. His audiences were the fickle voters of the democratic assembly or the great mob juries of the law courts, consisting of 500, 100, or 1500 jurors. As a result his methods, judged by any standard, are not above reproach. We are amazed to find in the same speech in juxtaposition "two most unlike appeals, the one the appeal to noble generous civic pride and patriotism, the other to the universal enjoyment which a mob finds in seeing a man pilloried with ridicule and invective." But while the falsehood and vulgarity which Demosthenes employed to win a point against an opponent are not glozed over, it is the way he adapts his larger oratorical technique to secure action in a noble cause that Mr. Adams stresses. Earnestness, severity, elevation, power marked his oratory—with a language amazingly simple and unadorned. His was a protean genius. All the devices of rhetoric were at his command. He was the master of those who spoke.

The last half of the book, after a brief precis of rhetoric, traces Demosthenes' influence down on succeeding ages. The public* life of Greece after the death of Demosthenes gave little opportunity for the exercise of the type of oratory for which he had stood. The oratory of flattery and encomium took its place, founded on the florid Gorgian-Isocratic rhetoric and Aristotelian argumentation. Though occasional Greek commentators recognized the power of Demosthenes it was left for Cicero, his great Roman rival, to give him his position of absolute primacy among the orators of antiquity. Cicero had spent much time in the university cities of Greece and of Asia Minor and had studied Greek oratory profoundly. He recognized the master speaker though his own style was rather in the Gorgian-Isocratic tradition and he showed none~ of the Demosthenic restraint. The reputation which he gave to Demosthenes was accepted by a world which looked upon Cicero as an authority and thus has been handed down to modern times.

Throughout antiquity and the mediaeval period the study of Demosthenes survives on the Continent—in the rapid sketch of Chapter IVdown to our own day and to the Demosthene of Clemenceau. In England in the sixteenth century we find Roger Ascham bringing the works of the great Athenian to Queen Elizabeth at a time when she was facing her desperate struggle against a modern Philip. Later the rise of democracy and of parliamentary oratory gave added impulse to the study of ancient rhetoric and Demosthenes and Cicero were established as twin authorities in the great public schools. Eton College, the "training school of British statesmen," alma mater of the elder Pitt, of Canning, of Wellesley and of countless others whose names are famous in English oratory, sent its alumni to Oxford or to Cambridge thoroughly trained in these authors in theoriginal. Though the ornate style of Cicero was more congenial to the majority than the simplicity of the Greek. Mr. Adams finds the subsconscious influence of Demosthenes in many, more particularly in the two Pitts, Grattan, Fox, Canning, Lord Brougham and Lord Wellesley.

In America, even at that early day, the classical training was weaker than in England. All college graduates knew Latin well, but few had thoroughly mastered Greek. Hence Cicero and the British orators were a stronger influence than the less familiar Demosthenes. Such was the case with America's greatest orator, Webster. When he graduated from Dartmouth he carried into public life only the college boy's knowledge of Demosthenes. Rufus Choate, on the other hand, second only to Webster among our orators, was not only a brilliant classical scholar during his undergraduate days at Dartmouth, but devoted himself to the study of Demosthenes throughout the busy years of his professional life. The fruit of this study appears in the purity of his style, singularly tree from the bombast and the artificiality which were the curse of the age.

And so on, without special pleading, Mr. Adams traces the permanence of the influence of Demosthenes. He has not been led astray by the temptation to emphasize unduly reminiscences of thought or of phrase, as so many have in similar essays. His exposition is sane and authoritative and happily free from extravagant claims. The volume is a model for the correct popular treatment of a profound theme and will well repay the reading by all who are interested in ancient life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S 158TH COMMENCEMENT

August 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICIAL FITNESS V.

August 1927 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D., -

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1927 By J. R. Chandler '98, Clarence G. McDavitt '00 -

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES HOLD MEETING IN HANOVER

August 1927 By Hanover, N. H.,, E. K. Hall -

Sports

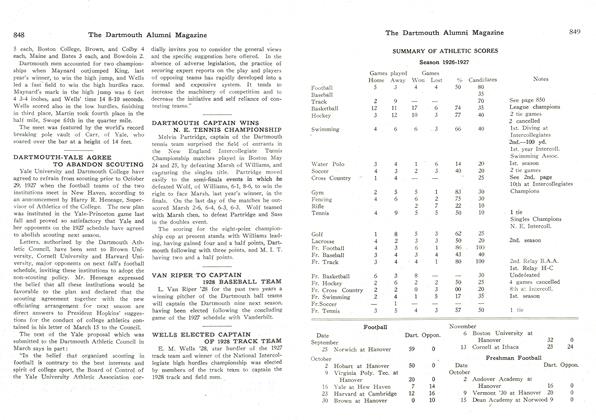

SportsSUMMARY OF ATHLETIC SCORES

August 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

August 1927 By Herrick Brown

Edwin J. Bartlett

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleDR. NATHAN SMITH'S LECTURE ON CHEMISTRY

March, 1911 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

ArticleTHE CHEMICAL LABORATORY

By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Books

Books"Portraits of a Half Century"

January, 1926 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

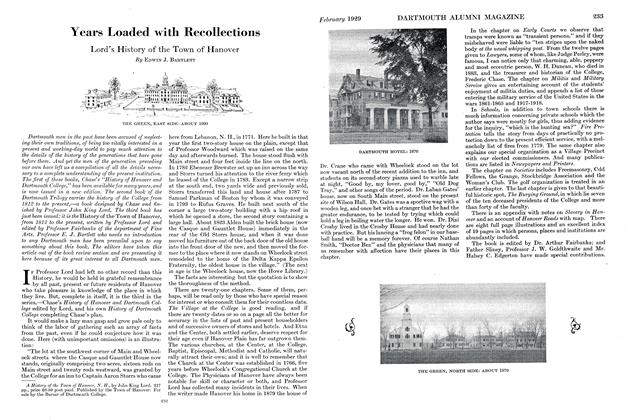

ArticleYears Loaded with Recollections

FEBRUARY 1929 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

ArticleThe Vicissitudes of South Hall

APRIL 1929 By Edwin J. Bartlett

William Stuart Messer

Books

-

Books

BooksWorking for a Cause

February 1977 By EVERETTW. WOOD '38 -

Books

BooksDEVELOPED LESSONS IN PSYCHOLOGY.

FEBRUARY 1930 By Gordon W. Allport -

Books

BooksSELECTIONS FROM ANCIENT GREEK HISTORIANS IN ENGLISH,

October 1939 By H. E. Burton -

Books

BooksMARRIAGE.

JUNE 1969 By LOUIS WOLF GOODMAN '64 -

Books

BooksA YEAR AND A DAY.

OCTOBER 1964 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

Books'The Way a Mouse Waltzes'

June 1975 By STEARNS M ORSE