In the interesting speech on "The Art of Being a College President," by President Wilson of Princeton University, at the inauguration of President Richmond of Union College, in 1909, he frankly confessed that according to his experience, members of college faculties were about as sensitive as singers in church choirs. In our benign academic life at Dartmouth no such admission is to be made, when one begins to talk about the inside view of faculty activities; but it must be said, at the start, that our duties and our preferences are so varied and our numbers are so great, that none but the most superficial and general remarks are possible.

Is there any art of being a professor? If so, how can it bind together, or even correlate, labors so dissimilar as those of the teacher of elementary French and the teacher of mathematics; the professor of palaeontology and the professor of English literature; the investigator into historical sources and the student of plant-germs? A college is a conlegium of quarternions and philosophy and civil engineering and linguistics and a good many things besides. What one demand can we properly make of a teacher as such, without immediate relation to his specialty ?

In the first place, it must be remembered that the present speaker is delivering neither an autobiography nor a prescription; he is merely summing up a few points concerning which his experience, and universal experience, would seem to leave little doubt.

The primary assumption ought to be that a teacher knows his subject. The one thing which is intolerable, from the point of view of everybody, from trustee to freshman, is a man in the desk who does not know the thing he professes to expound. Such a personage has been visible, from time to time, in the American academic field. A story used to be told of an estimable middle-aged gentleman who at length realized his lifelong ambition to be a professor of something, he did hot care what, in his alma mater. A combination of piety and log-rolling at last achieved his hope; and on the way to assume his duties he carefully perused, on the train, an elementary text-book on the subject he was to teach. Such a man, it is safe to say. could not get elected in any decent American college today. Two things all students, abominate: one is ignorance (on the part of the teacher),and the other is egotism (also on the part of the teacher. The latter they will tolerate, in the person of an unquestioned master in his field; but the former, never. And among their elders, in these days of subdivided learning, there is no disposition to allow any combination of agreeable personal qualities to take the place of downright intellectual competence.

But to competence must be added, every day of the academic year, an unquestionable power to teach. Paraphrasing the biblical sum ,in addition, the professor must add to investigation, knowledge; to knowledge, wisdom; and to wisdom, the .ability to impart it. To begin with, he must cause the student to know facts, but he must-both allure him and direct him to arrange those facts, in his own mind, in such a way as to leave a large residuum of exact learning, in the best sense, with its concomitant of a developed character.

President Tucker used to emphasize The Search for Truth as the great function of an institution of learning. This search should forever be an inspiration to teacher and taught, whether in the laboratory or in the realm of philosophy or belles-lettres. The relation between instructor and student, rightly defined, can be nothing but that between the stimulating and the stimulated. The personal influence is the final one. If learning is not a process of transmission it is naught. This "human element," which President Nichols makes almost the foundation of his administration, is indispensable. No amount of mere acquisition on the part of the teacher can take its place- If the instructor has nothing to transmit, he should never have been elected. If he lacks the power to transmit, he should be requested to resign. The things a teacher is remembered for, long after he has left his desk, are likely to be those of the heart rather than of the brain.

The instructor of the old type, at his worst, lacked the thorough equipment of his modern successor, and was inclined to cover his superficiality by too close an adherence to the pages of the text-book. At his best he was a man whose knowledge was all the more trustworthy because he had so largely attained it by unaided original work; and whose zeal of discovery he was determined to share with his pupils, immature though they were. The instructor of the new type, at his worst, knows all about Patagonian skulls in the fourteenth century, or the infinitive in n in Chaucer's "Canterbury Tales';" but he ill conceals his contempt for the average freshman or for his "generalizing" associates on the facility, who possess no degree save an honorary A.M. At his best, he teaches the history of society, or the great human element in the "Canterbury Tales," all the better and more inspiringly because he has a sound knowledge of externals as well as of internals.

But I must pass, in my brief time, to a few more specific topics. For one thing, I think that no man realizes now much of "Faculty Work from the Inside" is outside the class-room. "You must have an easy time," says the busy lawyer or journalist or physician or business man to the college teacher, "with from six to fifteen hours of work a week, and nothing else to do but study or rest." On the contrary, the classroom, or even the more time-consuming laboratory, takes but the smaller part of the effective teacher's time, at least after he has reached the age of thirty-five or forty. One is sometimes tempted to say that his work begins, not ends, when he leaves his desk. A few examples will prove the exigence and the time-taking character of our collateral work.

For one thing, the modern college depends largely upon an efficient committee system. To some committee almost every professor and assistant-professor is assigned, his duties involving an amount of work differing, of course, at varying times of the year, and in the several committees, but always time- and strengthconsuming. A member of this year's Committee on Administration tells me that the sessions of that particular committee, thus far in the academic year, have consumed fifty hours. Informal help to students-—aside from the new system of "advisorship"—is another pror fessorial occupation of greater importance, sometimes, than class-room instruction. Undergraduates' inquiries and requests range from questions concerning a text-book topic to discussions affecting their entire future career. Such character-shaping is one of the boons of the teacher's life—a thing that reacts to his own lasting benefit as' a man. Again, the informal employment-aid bureau which the college has furnished from time to time has, in the case of at least one professor, taken fully a quarter of his working hours for a considerable period. Aid to students by no means stops with their undergraduate days; scarcely a mail comes to one of the older teachers without some letter of request: please help me get a better place; please give me a course of reading on a specified topic; please look out for my brother in the incoming freshman class; please come and speak at the dedication of our new library, or school-building; please look over my MS. book, tell me its defects, rewriting what seems to you faulty, and advising me regarding a publisher, etc. One of us gets one kind of letter, another another; but this sort of correspondence probably comes to the college teacher more frequently than to any other professional worker.

Sometimes, too, the professor must be a combination of architect, contractor, and loan agent; at least four chapter-houses of Dartmouth secret societies have been built under the daily supervision of faculty members. When I add to this list, Bible-class leadership for a series of weeks; literary-class direction; collateral work as class-secretary, and so on, it will be seen that the time winch the earnest and ambitious teacher wishes to devote to investigation or authorship is seriously invaded. In this random list I do not mention summer-school work, which is paid, for; but manifestly that work must be done by somebody, and it often falls upon those who are most pressed otherwise, or are most desirous of doing something besides teaching six additional weeks.

Any superfluity of time left after the doings enumerated above is very likely to go to .addresses or papers.—local, before various -Hanover organizations ; or non-local, before learned societies, literary clubs, churches (professorial sermons are not yet extinct), School-graduation audiences, conventions, and the like. May I say, merely as a personal illustration, that this talk of mine the eighteenth address which I have given during the present college year, outside of the class-room, and that four more are to come.

Any mature man in any community, of course, should stand ready to help along the good motions of the world to the best of his ability. To this obligation college professors everywhere notwithstanding the time-honored jokes regarding their incapacity to take part in practical affairs—naturally expect to rise. But civic, social, and other calls come to the Dartmouth instructor with far greater frequency than in most college towns. There are great universities in great cities, and small colleges m good-sized towns; but nowhere else in the United States is a college of twelve hundred students situated in a village of no more than fifteen hundred inhabitants,—with no city of ten thousand people within seventy-five miles of it. Hanover, therefore, since the days of Eleazar Wheelock's primitive saw-mill has had to rely, in large measure, upon the college faculty for serviced usually done by other 'citizens. The extent and variety of such service, when tabulated, is rather impressive. With no endeavor to make a complete list, I can recall that members of our faculty, within my term of service, have been Moderator of the town-meeting; Moderator of the school-meeting; Moderator of the precinct-meeting; Commissioner of the precinct; Police judge; Supervisor of the check-list; Representative in the legislature; Member of the board of health; Member of the village improvement association; Member of the village tree association; Member and chairman of the law and order league; Director of the cemetery; Manager of the gas-works; President, secretary, treasurer, and manager of aqueducts (two) ; President, member of the corporation, and trustee of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital; Vice-president, member of the corporation, and trustee of the Howe Library; Trustee of the town library; Trustee of the savings-bank; Member of the school board; Architect of the enlargement of Rollins Chapel; Director and trustee of the Pine Park Association; Director and trustee of the Country Club; Director and trustee of the Stock-bridge Association (boys' club) ; Deacon or warden of church; Treasurer of church; Superintendent of Sunday-school: Teacher of Sunday-school; Organist; Choir-leader; Director of choral club.

It goes without saying that nearly all of these willingly-assumed obligations are gratuitous, and that some of them take, for considerable periods, a large percentage of a man's time and strength.

Is all this an educational waste? I think that a negative reply is warranted on two grounds: that the Dartmouth teaching-force has not been esteemed, in general, to be any less efficient, in its regular work of instruction, than similar faculties in larger towns; and that the students listen far more willingly and receptively to those whom they know to have "done something" outside of the class-room. Indeed, undergraduates are quite likely to speak with frank contempt of such of their teachers as apparently have no interests beyond the confines of a narrow specialty.

Finally, one of you asked me, before I began to speak, what, in my view, was the chief difference between the modern college and that of thirty, forty, or fifty years ago. In a word—the subject in itself demands a lecture—it seems to me that the undergraduate body of today shows a great gain in diffused facility, gentlemanly pleasantness, and average intellectual ability; with a loss in directive capacity and downright intellectual earnestness. Naturally, a large and prosperous college, of a cosmopolitan character, reflects, or shares, the characteristics of the large and prosperous country from which it is recruited. But the limitations are less striking, on the whole, than the gains. And there certainly is a place for the college—for this college—as over against the university, so long as all who teach remember the old and sacred emblem of proper instruction : a large torch, burning with ever-living fire, from which a surrounding circle of smaller torches eagerlv catches the flame.

Summary of remarks made by Prof. Charles F. Richardson at the meetingof Dartmouth Secretaries in Hanover, March 10, 1911

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

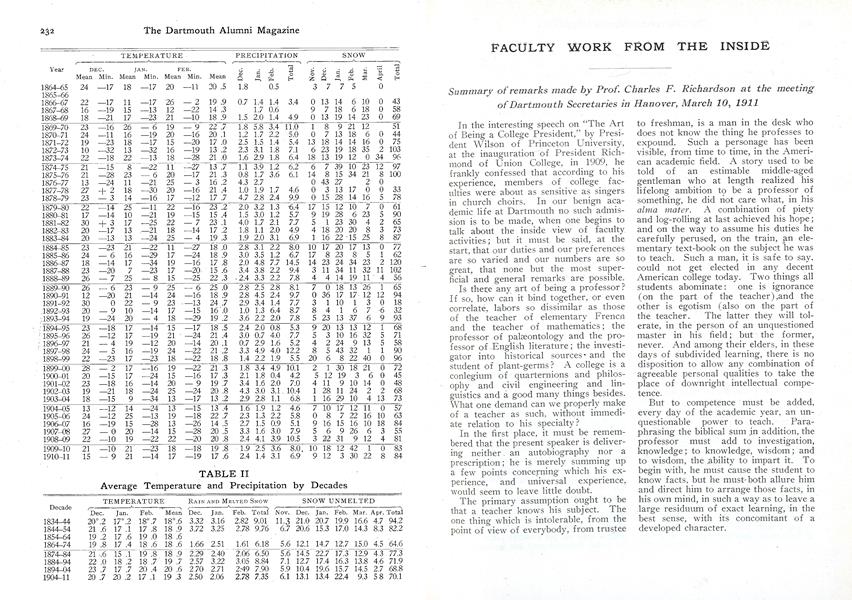

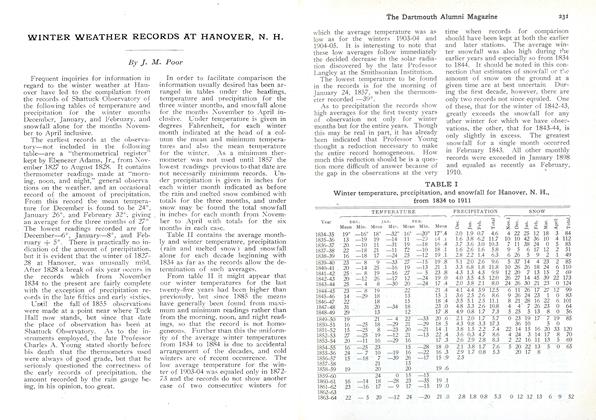

ArticleWINTER WEATHER RECORDS AT HANOVER, N. H.

May 1911 By J.M. Poor -

Article

ArticleAn alumnus of the College, now engaged

May 1911 -

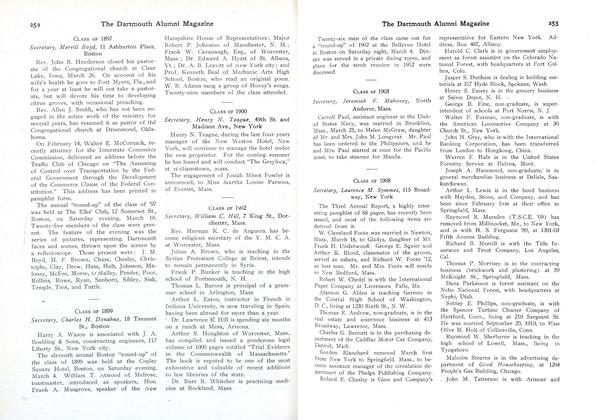

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

May 1911 -

Article

ArticleTuck School Conference on Scientific Management

May 1911 -

Article

ArticleBaseball

May 1911 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1908

May 1911 By Laurence M. Symmes