As it is the function of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE to keep the alumni of Dartmouth informed upon the month to month happenings in the College, so may well be its function, once each year to review the progress of the institution during the past twelve month, to point out the salient features of the period an to draw such conclusions as the necessarily near perspective will allow. To this end the managing editor of THE MAGAZINE has taken it upon himself to otter a brief review of the course of things in general, while he has called upon an received ready response from the heads of special departments of the College m the- matter of the work under their immediate care. The progress of the Medical School, the Thayer School and the Tuck School will be found separately reviewed by officers of those institutions; as will that of the athletic organizations and the Dartmouth

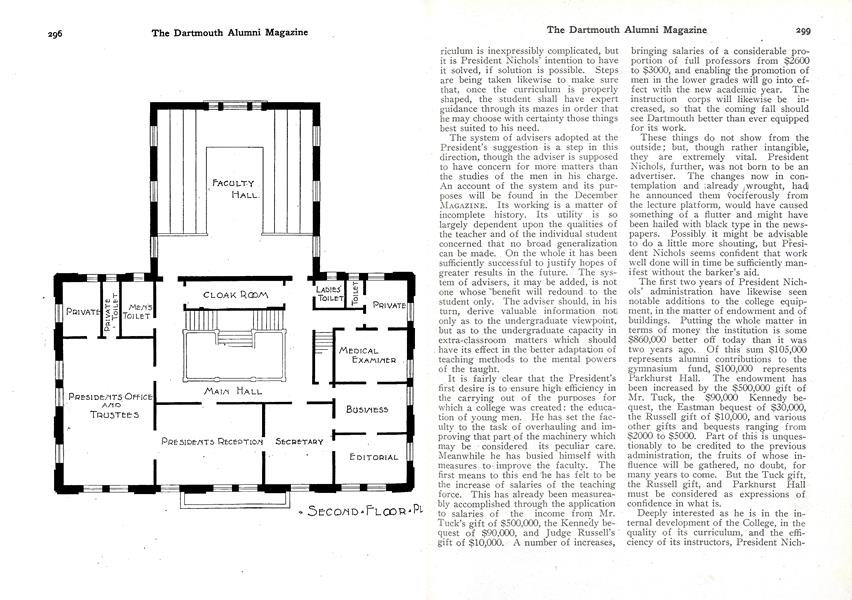

In so far as the College is concerned, the first question that arises in the mind of every alumnus has to do with the new administration. It has been in operation now for two years; what has it accomplished and what may be expected of it in the future? The administration of a large and growing college is, to be sure, much more than one man. Next year, in addition to the President there will be the Dean, the Assistant Dean, the Registrar, the Secretary, the Treasurer, the Auditor, the Superintendent of Buildings, the Medical Director, and the various assistants, all housed in the new building which stands a monument to the generosity of Mr. and Mrs. Parkhurst. The faculty likewise dabbles in administrative matters, indeed appointing the so-called committee, on administration that has to do with all matters of undergraduate discipline and is a general receiving station for problems that no one else will tackle.

But to the average observer the president of a college stands as its administration. The appointment of the other officers is largely in his hands, and reflects, in considerable measure, his policies and his judgment. What then of President Nichols?

If the function of a college president were a fixed quantity the question were easier to answer. One would have but to measure the man against the predeteimined requirements to give reply m terms of reasonable exacitude. But the function necessarily varies with the man, his personality and his training. President Nichols is a scientist, trained as a teacher Experience as a member of various college faculties and with .various college administrations has made him a believer in faculty rather than administrative domination. Yet the leadership has come entirely from him; the faculty has originated nothing. Its committees have faithfully labored with the problems presented to them by the President and have rendered reports, long debated, amended, and accepted with what should prove beneficial results.

One measure of particular importance is already on the books, will go into effect next year, and was reviewed at some length in THE MAGAZINE for June. Its aim is to improve the undergraduate standards of scholarship; its provision is to increase the minimum requirement m half of each student's courses from a mark of 50 per-cent to that of 60 per cent. Faculty committees are likewise studying problems affecting the efficiency of the curriculum. An exhaustive investigation is being made of the various courses offered, their intrinsic value and their relation to an ideal scheme of well balanced work. Changes in the character of some courses have already been suggested; the hours at which certain other courses are held have been discussed. The problem of a perfect curriculum is inexpressibly complicated, but it is President Nichols' intention to have it solved, if solution is possible. Steps are being taken likewise to make sure that, once the curriculum is properly shaped, the student shall have expert guidance through its mazes in order that he may choose with certainty those things best suited to his need.

The system of advisers adopted at the President's suggestion is a step in this direction, though the adviser is supposed to have concern for more matters than the studies of the men in his charge. An account of the system and its purposes will be found in the December MAGAZINE. Its working is a matter of incomplete history. Its utility is so largely dependent upon the qualities of the teacher and of the individual student concerned that no broad generalization can be made. On the whole it has been sufficiently successful to justify hopes of greater results in the future. The system of advisers, it may be added, is not one whose'benefit will redound to the student only. The adviser should, in his turn, derive valuable information not only as to the undergraduate viewpoint, but as to the undergraduate capacity in extra-classroom matters which should have its effect in the better adaptation of teaching methods to the mental powers of the taught.

It is fairly clear that the President's first desire is to ensure high efficiency in the carrying out of the purposes for which a college was created: the education of young men. He has set the faculty to the task of overhauling and improving that part of the .machinery which may be considered its peculiar care. Meanwhile he has busied himself with measures to improve the faculty. The first means to this end he has felt to be the increase of salaries of the teaching force. This has already been measureably accomplished through the application to salaries of the income from Mr. Tuck's gift of $500,000, the Kennedy bequest of $90,000, and Judge Russell's gift of $10,000. A number of increases, bringing salaries of a considerable proportion of full professors from $2600 to $3000, and enabling the promotion of men in the lower grades will go into effect with the new academic year. The instruction corps will likewise be increased, so that the coming fall should see Dartmouth better than ever equipped for its work.

These things do not show from the outside; but, though rather intangible, they are extremely vital. President Nichols, further, was not born to be an advertiser. The changes now in contemplation and ; already , wrought, had he announced them vociferously from the lecture platform, would have caused something of a flutter and might have been hailed with black type in the newspapers. Possibly it might be advisable to do a little more shouting, but President Nichols seems confident that work well done will in time be sufficiently manifest without the barker's aid.

The first two years of President Nichols' administration have likewise seen notable additions to the college equipment, in the matter of endowment and of buildings. Putting the whole matter in terms of money the institution is some $860,000 better off today than it was two years ago. Of this sum $105,000 represents alumni contributions to the gymnasium fund, $100,000 represents Parkhurst Hall. The endowment has been increased by the $500,000 gift of Mr. Tuck, the $90,000 Kennedy bequest, the Eastman bequest of $30,000, the Russell gift of $10,000, and various other gilts and bequests ranging from $2000 to $5000. Part of this is unquestionably to be credited to the previous administration, the fruits of whose influence will be gathered, no doubt, for many years to come. But the Tuck gift, the Russell gift, and Parkhurst Hall must be considered as expressions of confidence in what is.

Deeply interested as he is in the internal development of the College, in the quality of its curriculum, and the efficiency of its instructors, President Nichols is by no means indifferent to the requirements of material equipment. No one has been more interested than he in the gymnasium and in Parkhurst Hall. The improved quarters for the Thayer School have had his approval and aid. He has stated clearly enough that a new and sufficient library is an absolute necessity; and not only a building, but a fund to keep up a proper supply of books. He feels, further, that the library should be the dominating feature of the college buildings, the great intellectual power-house of Dartmouth. $250,000 should erect the building, another $250,000 should prove, for the present, a sufficient endowment fund for books. The man, or the men, to provide these things have not yet discovered themselves. But for someone here is the great opportunity.

In his relations with the faculty President Nichols has shown himself ready to work with his subordinates to the better upbuilding of Dartmouth. Those investigations which are most vitally of faculty concern he has turned over to committees of that body. That he expects of every man the best that is, in him is no secret. At the same time he has the wisdom to recognize clearly that there may be different orders of ability each deserving of recognition. He perceives the individual value of the teacher, the administrator, the investigator, and would give to each the opportunity to show his mettle.

In filling vacancies in the higher faculty grades, President Nichols has taken his time in order to avoid the possibility of error. The choice of Curtis Hidden Page to fill the chair of English Literature formerly held by Professor Richardson is generally regarded with great favor. The appointment of John Wesley Young in Mathematics seems equally happy. In seeking a librarian, he has continued patient investigation, entirely unmoved by the demand of others for haste. When the librarian is found, he will be the right man for the place, which, in view of present cramped conditions and future vague hopes, is an unusually difficult one. The placing of Professor Laycock in the office of Assistant-Dean was in wise recognition not only of present fitness, but of the advisability of choosing a Dartmouth man for the position.

Year by year the Dartmouth faculty is gaining greater recognition in the academic world and beyond it. The Nation cites at least two of its members as among the authorities who give validity to its book reviews. Other men hold important positions in the learned societies of America. More men than ever are contributing to periodicals, or are producing books. One man has been chosen for special investigation by the railroads; another has been called to serve on the Public Service Commission of New Hampshire. Others have received recognition in the form of calls to neighboring institutions, in some cases too flattering to be refused.

The chief point of regret with regard to the faculty is that more Dartmouth men are not preparing themselves for "enrollment in its numbers. This is partly because Dartmouth graduates are tending to swing away from teaching as a profession, partly because of an insufficiency of graduate fellowships, and partly because of an unsatisfactory system of awarding the few that are offered. The situation is one, however, which may cause the alumni some concern and which it lies, in their power to remedy. Future issues of THE MAGAZINE will offer some suggestions in the case.

For a college president to grow into the undergraduate affections is a matter of long time. Traditions evolve about a president, as they do about an institution, slowly, as his personality gradually dominates or is gradually obscured. In one respect, at least, President Nichols has impressed himself upon the undergraduates: they know that he, is fair and that his sincerest wish is to deal justly with them, to be accessible to them at all times, to know them and to be known by them. His home offers them at all times a warm welcome, and the charm of cordial hospitality. He has had the wisdom to meet them from time to time as a body, to talk frankly with them, to take them into his confidence; and they have responded well with loyalty and respect. That mellowing years will increase the sympathetic understanding between the President and the undergraduates there can be no doubt. In fact, by the time he has conferred the bachelor's degree upon the members of the class who were freshmen at the time of his inauguration, it is safe to prophesy that he will be firmly intrenched as one of the best loved presidents in the country.

The growth of Dartmouth's undergraduate enrollment year by year has been a source of pride to alumni as an indication of .increasing popularity and prestige on the part of Dartmouth. In the fall of 1908 this, growth encountered a sudden check, the freshman registration dropping from 357 of the previous year to 334. In the fall of 1909 it had dropped to 3.09. Last fall it rose again suddenly to 398. There is reason to expect another large class this year. In size then, the College is continuing the progress of the past. Indeed, it may well be advisable, in the near future, to put a definite limit Upon the student enrollment. When the 1500 mark is reached the most sanguine should be more than satisfied.

In so far as concerns the traditions of the College, its democracy, its spirit of vigorous independence, its respect for achievement,—those things are as safe today as they ever were. There is less crudeness than there was a quarter century ago, and good manners count for more than they once did. Some of the older fraternities may, at times, show too much concern for the cut of a candidate's coat and too little for the packing of his brains. When they do, the small fraternities carry off the honors, which is the best indication of a satisfactory condition of affairs. On the whole, it may be stated confidently that no college in the country has a healthier, saner student life than does Dartmouth; that no college turns out men who have better preserved their youthful enthusiasm, their idealism, their readiness to take a hand in whatever work the world may call upon them to perform. There is enough yet for the College to achieve, but there need be no question now that it is under the direction of one who, in building the future, will respect the admirable foundations of the past.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT WEEK

August 1911 -

Article

ArticleTHE AMOS TUCK SCHOOL OF ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE

August 1911 By William R. Gray -

Article

ArticleATHLETICS AT DARTMOUTH

August 1911 By George A. Graves -

Article

ArticleThe Death of Professor Wells

August 1911 -

Article

ArticleTHAYER SCHOOL OF CIVIL ENGINEERING

August 1911 By Robert Fletcher -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

August 1911