PROFESSOR LORD'S HISTORY OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, 1815-1909*

March, 1914 Herbert Darling FosterFor twenty-two years since the appearance of Frederick Chase's first volume, the alumni have been eagerly awaiting the second volume of the history of the College. After the death of Mr. Chase, the editing of the earlier volume fell to Professor John King Lord. Into his hands were entrusted the materials so carefully collected by the former treasurer of the College and the task of completing the story. The first volume has attained a notable rank among both college and town histories through Mr. Chase's drastic methods of search and his careful use of the material on the founding and first forty years of Dartmouth. It is doubtful if any other of the nine American colonial colleges has so varied and complete a collection of contemporary documents and printed matter from the very inception of the institution.

Professor Lord, therefore, had an exacting standard to meet; and he also had to make the two volumes harmonize in general treatment. Fortunately, both writers were trained in habits of exactness and precision, and each had the power of holding in mind and assimilating complex material. The two volumes possess a general similarity of treatment and style which give the desired unity, so that the reader does not feel a break as he passes from one to the other. The second volume, however, does not attempt to cover the history of the town save incidentally as connected directly with the College. It is to be desired, that Professor Lord, who has gone over the period and much of the material, should give us also a history of the town since 1815. He has had to cover about twice as long a time as in the first volume, the administration of eight presidents and two antipresidents, and also to treat the story of recent years where the material has not yet been assembled or subjected to historical criticism, and in a period, some of it controversial, where he himself has been an actor under the administration of four presidents. Oil the other hand, the author has had firsthand knowledge of Dartmouth men and things since he entered College in 1864, and of course earlier, through his relation to President Nathan Lord. The trebly difficult task has been carried to a successful issue, and the opportunity to make use of both documentary and personal knowledge, has been wisely utilized, and, so far as the reviewer has been able to discover, without violating sound principles of fairness and historical criticism.

If one is tempted in the first two chapters to query whether President John Wheelock receives a fair deal, a rereading of the matter and a comparison with the involved statements of the second president, in his Sketches and other documents, leave one with the impression that the facts, lamentable, but true, warrant the author's conclusions and his frank, but fair, criticisms.

In general, while there is no lack of the incisiveness which one would expect and desire from the grandson of Nathan Lord, there is a judicial tone so woefully lacking in much of the controversial writing and in at least some of the actors in the more bellicose Dartmouth days. A certain reserve and balance are especially shown where decided restraint and detachment were clearly needed and evidently exercised, in the discussion of the administrations of Presidents Bartlett and Tucker, in which Professor Lord was himself so active a participant.

The alumnus who is a lawyer or keenly interested in constitutional questions will be likely to pass by the introductory chapter on the college church and the causes leading up to the great controversy, and begin with the following chapter on the College and the University and the Dartmouth College' Case.

Whatever his profession, the graduate is likely to turn to the chapter describing the administration of the College in his own unregenerate days. Nathan Lord, President Smith, "Bully" Sanborn, President Bartlett, President Tucker are names for memory to conjure with, and the memories will not let the graduate lay down the book, if his evening is free, until he has dipped well into the history which he himself helped to make in "the good old days", when it is barely possible the gentle reader was particeps criminis.

If the gentle or general reader is like the average alumnus with whom the reviewer has conversed, he will be also likely to cut the leaves in the latter part of the book, and read the entertaining cross-sections describing social and economic conditions under the admirably treated sixteen "Special Topics" which follow the narrative history Every Phi Beta Kappa man will want to read the account taken largely from Mr. Chase's address at its centennial in 1887. Men interested in music will be interested in the remarkable work of the Handel Society, which Ritter, in his History of Music in America, placed next to the Boston Handel and Haydn Society as most beneficial in its influence. The records of the Handel Society for 1839, show that the "Singout" preceded that period. "On Tuesday, July 16th (1839), the senior members of the Society (according to an ancient custom), sang Amesbury from the 'Village Harmony', this being the close of the college studies of the senior class." The sinking to the tune of Amesbury, "according to time-honored usage, of Wesley's old anthem, 'Come let us. anew our journey pursue'," is mentioned by Professor Crosby in his Memorial of College Life, as being customary as early as President Tyler's administration, 1822-28. Class ' day dates from 1854. To "the miserable fiction", as the late Professor Richardson called it, that Webster destroyed his diploma because he had not been awarded the valedictory, Professor Lord gives effective, and it is to be trusted, permanent quietus on the testimony of Webster's classmates, Merrill and Reverend Elijah Smith.

Old fashioned as are the College Laws of 1779 it is refreshing to find that some of the eld traditions have not failed. "They shall be in the Hall [for chapel] and at their places by the time the signal given for their coming; together ceases, at least before the President or the person who is to perform the services enters the Hall, and shall remain there and behave with gravity and propriety and not leave their places till the President, Tutors, Bachellors, and all Senior Classes have gone out of the Hall." "That examinations be strict and critical" is doubtless regarded by some as still the policy of the college.

"Freshmen shall at times hereafter appointed for deversion do the necessary errands for alb the senior classes, who have themselves served a freshmanship" is still observed, though the old restriction, "provided they are not sent more than half a mile", is not always kept.

Among the most interesting topics are the discussions of means and routes of travel. In 1773 Dr. Pomeroy of Hebron, Connecticut, had waited . three months without finding a chance to send Wheelock a letter. Wheelock writes in that same year that it would take six days to reach Boston with the best of horses and at the best of seasons. In connection with the present plans for a new bridge of cement and stone, it is interesting to note that the average life of the first three bridges was about twenty-one years. The present Ledyard Free Bridge opened in 1859 "enjoys the distinction of being the first free bridge over the Connecticut River."

In the narrative portion of the history the two chapters on the successful resistance of- the college against the attempts of President John Wheelock and the State Legislature to overturn the charter and create a state University, move with swifter and less complicated pace than the preceding one on the causes leading up to the controversy. Webster's speech before the Supreme Court in this famous Dartmouth College case is quoted from the account written by Chauncey A. Goodrich, the Professor of Oratory at Yale, who had come on to Washington to listen in Yale's behalf. The stirring account was quoted by Rufus Choate in his oration on Webster, delivered at Hanover in 1853. It has been somewhat the fashion to discredit Goodrich's account as overdrawn, but there is confirmatory evidence of the closing et tu quoquo mi fili! in a letter of 1818 from Salma Hale to William Plumer printed in Webster's Writings and Speeches. "He appeared himself to be much affected; and the audience was silent as death. He observed that in defending the College he was doing his duty—that it should never accuse him of ingratitude—nor address him in the words of the Roman dictator." Additional confirmation of the nature and effect of the peroration is given in a manuscript of Justice Story of the Supreme Court, apparently written as a review of a volume of Webster's speeches published in 1830, but never printed until published by Everett P. Wheeler in his Daniel Webster,the Expounder of the Constitution, in 1905. This account, seemingly not available when the chapter in the History was written, says: "There was a painful anxiety towards the close. The whole audience had been wrought up to the highest excitement; many were dissolved in tears; many betrayed the most agitating mental struggles; many were sinking under exhausting efforts to conceal their own emotion. When Mr. Webster ceased to speak, it was some minutes before any one seemed inclined to break the silence. The whole seemed but an agonizing dream, from which the audience was slowly and almost unconsciously awakening."

As to the suggestion of Shirley in his Dartmouth College Causes, and of later writers like Lodge, who follow Shirley, that political pressure was put upon the Supreme Court in the vacation between the hearing March 10-12, 1818, and the decision rendered by Marshall, February 2, 1819, the History takes the ground that what the College did was to attempt to put before prominent men like Chancellor Kent the terms of the college charter, and a fuller knowledge than they had gathered through the preceding attempts of the opponents of the College. "The truth is, as Mr. Shirley himself conclusively shows, that the impartiality of the court was in fact endangered, in the manner above related, by the acts of some restless friends of the University, in a way that compelled the officers of the College to counteract their schemes. But there is no hint of anything else to be inferred from anything that the writer has been able to find."

Those who wish to understand Webster's position as to being retained by President Wheelock in 1815, two years before the college suit was brought, would do well to read his entire reply to Mr. Dunham in The Private Correspondence of Daniel Webster (IV, 251-3), which is more explicit and slightly more favorable to Mr. Webster than the impression one gets from the extract in the History. For his fee in the action before the Supreme Court, Webster received a thousand dollars, the exact amount given by John B. Wheeler of Orford, New Hampshire, to enable the College to bring suit, a gift which probably meant more to the life of the College than any equal amount ever received.

The wise and brave persistency of President Brown in the protracted and bitter struggle, is well emphasized. The tragedy of the situation is happily relieved here and there by the pictureesque actions of undergraduates .in Hanover, members of both the College and the rival University.

The treatment of President Nathan Lord's administration, 1828-1863, is interesting, both because of the development of the College, and also by reason of his strong personality, his pro-slavery views, and his consequent inability to concur with the pronouncements of the trustees in 1863. "In 1841, Dartmouth graduated 76, Yale 78, Harvard ,48, and Princeton 60. In 1842, Dartmouth sent out the largest class in its history till 1894, 85 in number, against 105 at Yale, 55 at Harvard, and 45 at Princeton." This was regarded then as "unexampled and almost unnatural prosperity as to numbers". The housing of the increasing numbers during this period was met by the erection of Thornton and Wentworth in 1828 and 1829, and Reed Hall, 1839-1840, the last on the site of President Eleazar Wheelock's Mansion House. This house was removed to its present site on West Wheelock St., where it now serves as the "Howe Library". The gambrel roof shown in the accompanying illustration, was unfortunately changed in 1846 to the present roof. The growth of the College was further marked by the establishing of "the Chandler. School" in 1852, and the building and equipment of the Shattuck Observatory under the direction of Professor Young, two years later.

Under the genial leadership of President Smith, 1863-1877, came the development of "the university idea" with the separation in the catalogue of the Medical, Academical, and Chandler Scientific Departments, the establishment of the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts at Hanover in 1868, and the organization of the Thayer School in 1871. In this chapter fall the description of the opening of Bissell Hall, the old gymnasium (now the Thayer School), in 1867; the establishment of compulsory "gym" under tutors Emerson and Worthen, the introduction in 1865 of baseball, the adoption of green as the college color the next year, and of the college yell of Wah-hoo-wah, devised by Daniel Rollins '79, the revival of the enthusiasm for boating, the observance in 1869 of the Centennial of the founding of the College, the adoption of the certificate system of entrance in 1876.

Doubtless the definitive history of the administration of President Bartlett and President Tucker must be written in a later generation, when a longer perspective is possible after the sifting of contemporary evidence and later accounts: indeed. Professor Lord disarms criticism by frankly granting this. What he has done, however, is to give an account which will stand as one which must be read by any one who would understand or write upon the period. In the administration of President Bartlett he deals with the increase of endowments and the building of Rollins Chapel and Wilson Hall, the improvement of the financial conditions and the definitive settling of the vexed question of alumni representation; and in the difficult task of discussing another college controversy, he has, to the reviewer's mind, set down naught in malice.

In President Tucker's administration he has shown appreciation, but self-restraint, in speaking of the development of the College, pointing out that "the extraordinary increase of the College, without a parallel in the older colleges of the country, is a conspicuous instance of the part that personality plays in the direction of educational, as of other, movements". With the completion of Dr. Tucker's sixteen years of service, the narrative closes; but the special topics bring the accounts of some features down to the present day.

The interest and historical value of the book are increased by the twentyseven really illustrative pictures of men and things, two of which are reproduced in this review. There are portraits of all the eight presidents treated in the volume; of William Allen, President of Dartmouth University; of Charles Marsh, of Woodstock, Vermont, who served the College as trustee forty years; and of Mills Olcott, treasurer of the College in the dark days, 1815-1821, trustee from 1821 to 1845, developer of the Olcott (now Wilder)- dam. and mill properties, and one of the most prominent business men of the region. Mills Olcott lived next the college church in the picturesque and venerable Olcott-Leeds house, built before 1797, in which, then used as an inn, Daniel Webster stayed when he came to enter college. In its parlor Rufus Choate was married to Olcott's daughter, Helen. As a parsonage. it was occupied by the saintly and quaintly humorous Dr. Leeds for the last half century. For the preservation of such a house alumni sentiment has reasons that may not lightly be set aside.

Four interesting views show the College in 1790, 1829-1845, 1852, and 1910. Memories of graduates will be stirred by the plan of the village in 1855, and by pictures of the Dartmouth Hotel in 1866, the Commencement Tent at the Centennial in 1869,-and the river before the building of the dam at Wilder.

Records of trustees and treasurer, and of the college church, state documents, letters in print and manuscript, contemporary books and pamphlets, newspapers, college memorabilia, printed reminiscences, diaries, college laws, and occasional bits of personal remembrance have been utilized with skill to give both .trustworthiness and picturesqueness to the story.

Altogether admirable is the plan of saving up for separate treatment at the end of the book the discussions of various organizations and activities. These contain a mine of interesting lore which involved varied and persistent delving. This "utilizing of the drippings", to use the culinary phrase of the learned Justin Winsor, not only gives valuable material in orderly form, but it relieves the narrative. of the overloading with unrelated digressions which" destroy the unity of many local histories. These special topics preserve much that was in danger of being lost, and reinforce the pertinent suggestion of Professor Lord in his preface: "I can but hope that coming generations of those having to do with the' College will be more successful in preserving docuSome adequate provision, probably in ments that have to do with its history, connection with the needed new library building, -should be made for the securing, calendaring, and proper preservation of materials for future history. The good habit of . presenting manuscript and other memorabilia has already been begun by alumni and friends of the College, and even by undergraduates, and needs only encouragement.

Professor Lord's difficult task has been performed with rare skill and discretion, and its author deserves not only a wide reading, but a very hearty and outspoken appreciation of his contribution to the history of the College.

If the alumnus who reads the book from preface to appendix yields to the temptation to stop and think over the hundred years of institutional life it covers, he is likely to detect a certain dangerous readiness for personal controversy; and, on the other hand, to recognize with profound gratitude, both the debt owed to men willing to stand courageously for principle, and also the power that has come to Dartmouth with the assumption of adjuster responsibility by the entire fellowship of the College. The History itself will in some measure serve to recall to alumni, present and future, the finer purposes of the College as set forth by President Tucker in his dedication of Webster Hall, on Dartmouth Night, in 1907: "to preserve the honorable and inspiring traditions of the College, to bring our illustrious dead into daily fellowship with the living, to quicken within us the sense of a common inheritance and of a common duty".

*John King Lord, A History of Dartmouth College, 1815-1909, being the second volume of A History of Dartmouth College and the: Town of Hanover Hampshire, begun by Frederick Chase. Concord, N. H, 1913. Published by the College.

The College Yard, 1829-1840 Wheelock's house is seen on the site of Reed Hall (From a History of Dartmouth College, 1815-1909, by John King Lord)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePHI BETA KAPPA CELEBRATION

March 1914 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCHICAGO ASSOCIATION

March 1914 By WM.H. GARDINER '76 -

Article

ArticleTHE HAZING PROBLEM IN 1765

March 1914 By ELEAZAR WHEELOCK., Yrs.E.W. -

Article

ArticleDISCIPLINE IN THE FRESHMAN CLASS

March 1914 By R.W. Husband -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

March 1914 -

Article

ArticleKNOWLEDGE, ART AND FELLOWSHIP

March 1914

Herbert Darling Foster

Article

-

Article

ArticleNEW SPORT BOOK FEATURES DARTMOUTH WINTER SPORTS

June, 1923 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

June 1948 -

Article

ArticleAugust Dates Announced for Third Alumni College

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Article

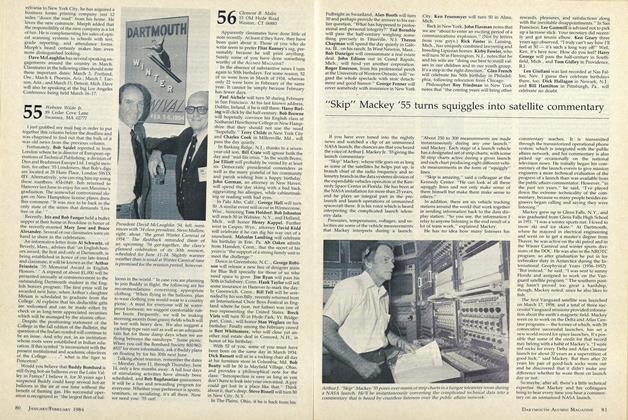

ArticleSkip" Mackey '55 Turns Squiggles into Satellite Commentary

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 -

Article

ArticleWhat Rold Do Schools Like Dartmouth Play in World Affairs?

APRIL 1992 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

December 1955 By HAROLD L. BOND '42