The following remarks were made by Professor Edwin J. Bartlett, at the mid-winter banquet of the Alpha of New Hampshire, Phi Beta Kappa, on February 17, 1914. After stating that he would confine himself to testimony on a single phase of the character of Professor Richardson, Professor Bartlett proceeded to analyze the causes of his popularity and effectiveness as a teacher as follows:

It is one of the greatest satisfactions and rewards of a college teacher to be honorably popular among the young-men that he teaches, and especially among the young men that he has taught. As years go by the man's judgment takes the place of the boy's, and what glitters as gold to youthful eyes may not stand the acid of mature analysis. To the popularity of the professor so many apparent qualities may contribute,—tradition and reputation, generosity; real courtesy, the bluff cordiality of the commercial traveler, a display of personal interest in his pupils, an air of worldly wisdom, intellectual brilliancy, notable power of expression, mere fluency, fairness, laxity to the degree reasonable but not excessive from the undergraduate point of view, stimulus without harshness or sting, a little thinly disguised impatience with the unreason of 'the other 'powers that be, the latest intellectual or economic novelty not usually exhibited to boys or virgins, conscientiousness rightly diluted with sweetness and light, even rigor after long years of results; not all these in one ; not all at one time. If then a teacher draws large classes whose members cannot possibly know him in advance, if he holds them with their increasing appreciation to the end of their college life, and continues in their esteem during the later years when discriminating memory and converse and comparison have separated the baser from the noble, if he. sustains both tests, he is genuine and his attributes can be a source of inspiration and help to those who remain or come after.

With the view of speaking upon this which I think the most important part of the work he did in the College, not as a judge or critic, but as a reporter or interpreter,. I have recently questioned a large number of former students whose time ranges from that of the last class he taught to more than twenty-five years ago, and whose occupations are sufficiently various. From some I have received written replies, from others freer oral opinion. My question has been what were the qualities which gave him both temporary favor with undergraduates and lasting favor among the graduates of the College; or what was the attraction, the reality, the memory.

There was substantial agreement in my assumption of his great favor and esteem, though not always in superlative terms; and from the many careful estimates I am sure that we can obtain a better understanding of this undeniable reality than in any other way.

From more than twenty-five years ago comes this impression formulated within a few days, — "C. F. Richardson was the first Dartmouth professor who ever asked me my opinion, and did it in such a way that it seemed as if he was actually going to modify or form his own opinion on the basis of it. On other occasions he spent a great deal of time and effort inducing me to change mine. The interest in both cases seemed personal, not controversial or professional. As a matter of fact in my time his popularity was not wide. The boys were slow to. respond to what was an innovation then. . . . But they began to appreciate the meaning of his attitude and prize him, after graduation. I think that I was one of the minority who felt grateful while under him."

Said a bright lawyer, a graduate of some sixteen years, in language that would be literature could I only remember it, "You went into a room where was a genial gentleman who evidently had just come from a good breakfast for which he was abundantly able to pay; he had a general air of comfort and of ease and of wishing you enjoyment of the same; he talked finely about something in which he was much interested and hoped that you would be interested too; he would be glad to help you if you were, but it did not disturb him at all if you were not. You had no responsibility whatever; if he asked your opinion upon some subject and you agreed with him it was well, but if you differed no harm was done."

Another said: "There was an air of refinement about the course and we thought it a good place to be;" another. "We had heard of Longfellow and Hawthorne and Whittier; we had some few notions about them and one likes to hear about things of which he has some previous ideasagain, "It was his humanity."

A very thoughtful and able man of about seven years ago makes this contribution, "I took his course in English Literature as so many others have done because it was sure to be easy; and I think that my impression of Professor Richardson up to the time I took that course was not one of the very wholehearted respect and admiration for him which I have since had. It was rather a critical attitude because he gave a course which every body knew was easy and did not seem to mind the fact that everybody knew it. I went to the course and found out instantly what kind of a man he was, and felt myself put up on a sort of pedestal because he had the faculty of making us all feel that we were his intellectual equals, that for example, we knew English Literature as well as he did, but that he simply happened to have made a more careful study of it than we, and had set a connected story of it into printed form. His entire modesty and his tremendously fascinating personality wholly aside from his literary and intellectual ability are the things that I shall remember about Professor Richardson both as a professor and an alumnus."

These testimonies come from very recent students, "He had a pleasant manner, a great fluency and ease in speech; he was especially apt at saying some bright thing without delay or hesitation: he was a stimulus, getting results without harshness." — "About the middle of his course you found that you wanted to read for yourself." — "lt was his projected personality; he fired your imagination ; he said what you thought but were unable to say." — "He was an absolute gentleman in appearance and speech, kind-hearted and courteous; a magnetic personality in or out of the classroom, and those who took his courses had to learn in spite of themselves" —Possibly some thoughts had crystallized into the expression, "Whscame to scoff remained to pray", as I have heard it applied to his courses several times.

From the keen analysis of a teacher in his own field, his pupil more than a decade ago, I can only draw quotations: "His attractions lay in the fact that he was able to make me feel that something more than an impersonal interest lay behind his encouragement. Each succeeding college generation entered his class prepared to be entertained, but not to work too hard. At last a 'surprise would come in the discovery that by almost uncanny intuition Professor Richardson had identified his intellect with that of his pupil. * * He respected his vocation * * He possessed unusual fluency and appositeness of speech. * * He made one believe that his friendship stretched beyond the classroom, through the college, into the world, to be drawn on as a positive asset."

Chatting for some time with a group of three who were about midway in his period of his service, I inquired: "Were {he qualities that you liked in him those that would have been as useful in other departments? Would he have been as successful in the department of mathematics, or physics, or chemistry?" The negative was so emphatic as to be a positive; and they added: "The man was made for his subject."

Each of my hearers will interpret in his own way. I learn that we are not ready yet to standardize the intellectual, social, and moral emanations, — the dynamics of a man.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMEETING OF DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES

April 1914 By W. Gray Knapp '12 -

Article

ArticleThe New Hampshire State Superintendent of Public Instruction,

April 1914 -

Class Notes

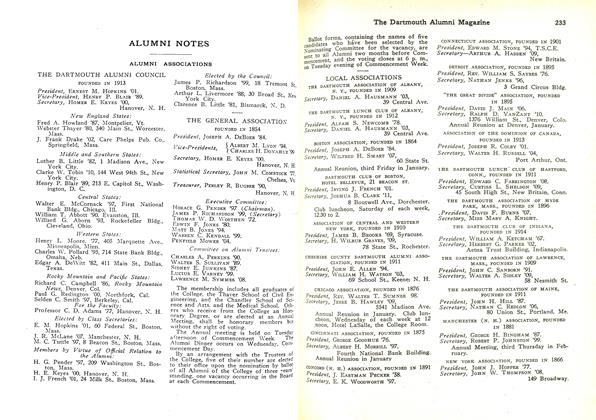

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

April 1914 -

Article

ArticleNOMINATIONS FOR ALUMNI TRUSTEE

April 1914 -

Article

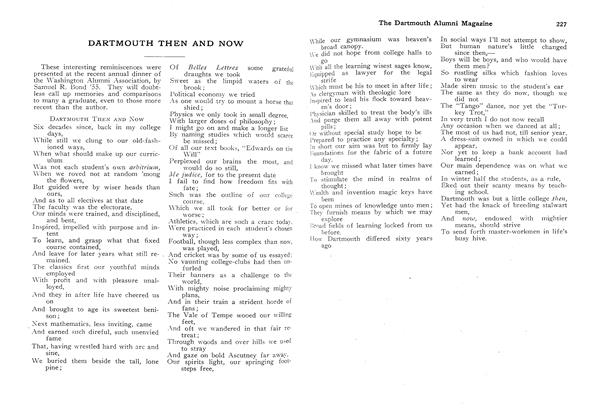

ArticleDARTMOUTH THEN AND NOW

April 1914 -

Article

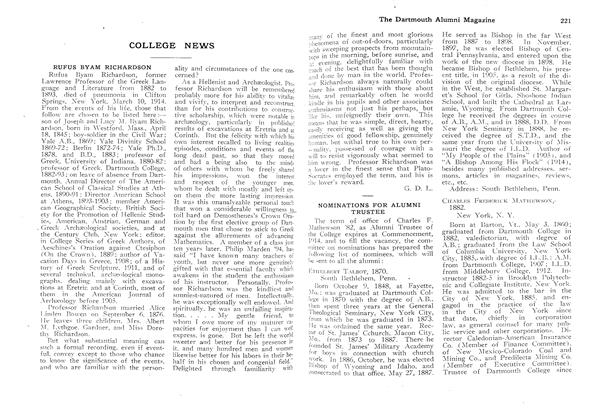

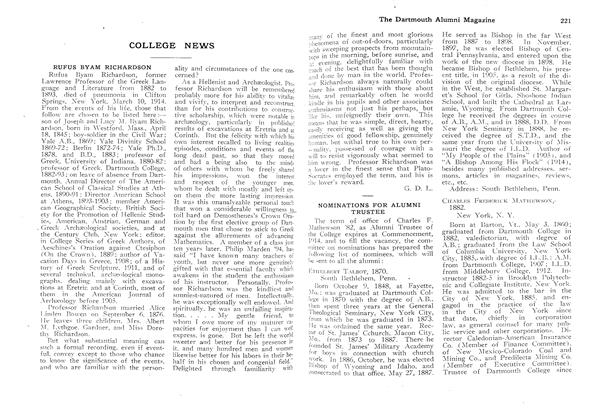

ArticleRUFUS BYAM RICHARDSON

April 1914 By G.D.L.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS' SPEECH AT CLARK COLLEGE

February, 1910 -

Article

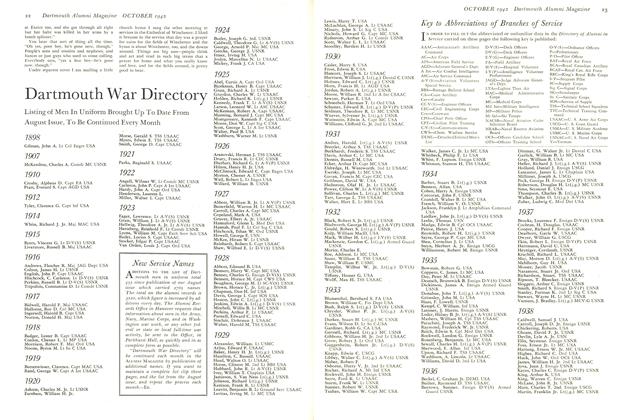

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

October 1942 -

Article

ArticleZiskind Lecture Fund

April 1956 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON ALUMNI PROJECTS

AUGUST 1930 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94 -

Article

ArticleA Note on the Election

October 1960 By RICHARD E. WRIGHT '54 -

Article

ArticleTallying the Alumni Fund

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Robert H. Nutt '49