During the year 1913 a group of prominent professors of several universities met to consider the feasibility of forming an association of teachers in higher institutions of learning, which should have as its most important object "to advance the standards and ideals of the profession." This group invited others to unite with them, and the whole number, consisting of thirty-four men, constituted themselves an organizing committee. The members of the committee were widely distributed geographically, being connected with institutions located at various places from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The institutions with which they were connected were of many different types, both state and private. The men, moreover, were scholars of high reputation in many lines of intellectual activity, chiefly in departments of the liberal arts.

The committee worked for several months to arrange plans for a meeting of those interested in the project, and to prepare a tentative program of future activities to be discussed at the meeting. They then selected about fifteen hundred professors in the United States, chosen on the bases of rank and scholarship, and invited them to be present at a meeting to be held on January 1 and 2, 1915, in New York City. Along with the invitation went a circular, defining the objects the committee had in mind in attempting to form the association. The first paragraph reads as follows : "The scientific and specialized interests -of members of American university faculties are well cared for by various, learned societies. No organization exists, however, which at once represents the common interests of the teaching staffs and deals with the general problems of university policy. Believing that a society, comparable to the American Bar Association and the American Medical Association in kindred professions, could be of substantial service to the ends for which universities exist, members of the faculties of a number of institutions have undertaken to bring about the formation of a national Association of University Professors. The general purposes of such an Association would be to facilitate a more effective co-operation among the members of the profession in the discharge of their special responsibilities as custodians of the interests of higher education and research in America; to promote a more general and methodical discussion of problems relating to education in higher institutions of learning; to create means for the authoritative expression of the public opinion of college and university teachers; to make collective action possible; and to maintain and advance the standards and ideals of the profession."

It is evident that there were two very distinct ideas in the minds of the committee. The first was to improve conditions of scholarship among faculties and students. Accordingly they suggested that if an association were formed, it should at an early time consider such subjects as the relation of instruction and scholarship, the adjustment of graduate to undergraduate in- struction, and many similar topics. The second point is that they felt it desirable that faculties should have a greater degree of influence in administering institutions of learning, and in determining their policies. This is best expressed in the words of the circular. The committee wished the association to consider "the proper conditions of the tenure of the professorial office; methods of appointment and promotion, and the character of the qualifications to be considered in either case; the function of faculties in university government; the relations of faculties to trustees; the impartial determination of the facts in cases in which serious violations of academic freedom are alleged."

The committee further advocated the establishment of some form of publication, which should contain the proceedings of the meetings of the association, which should be the vehicle whereby the decisions of the association might be made public, and which should give an opportunity to individual members of the association to make contributions to the subjects that might be under discussion by the association. "It would also appear desirable that the Association should, as soon as its financial condition makes this possible, establish an annual, semi-annual or quarterly periodical, devoted to the discussion of similar questions and to the interchange of information respecting the policies and activities of the different universities."

To the fifteen hundred invitations to the meeting about six hundred and seventy-five favorable replies were received. These were from those who expected to attend the meeting, or from those who were unable to attend, but expressed sympathy with the cause, and a desire to become affiiliated with the association, provided an organization were effected. About two hundred and seventy-five or three hundred were actually in attendance at the meeting. There were three sessions of the meeting, lasting for a total of more than nine hours. An association was formed, a provisional constitution adopted, and officers and a council elected to formulate plans for the next annual meeting.

At the first session several brief addresses were given, for, the most part by those who had been requested some time in advance by the committee to state reasons for the formation of an association, the principles upon which the association might be successfully established, and various ideas which the association should not adopt. All of these addresses had the characteristics of moderation and reasonable conservatism. The following are some of the more striking ideas presented in these initial addresses: (1). The purposes of the committee in effecting an organization minimized the danger that the association might become a trade union. (2). The association, realizing the danger it incurred of failing in its purpose through a misunderstanding of its aims, should go on record as to what it did not want to do. (3). The controlling motive in forming the association is a profound interest in the profession. (4). Academic freedom should be understood to mean the ability and will to assume responsibility, not the avoidance of it. (5). The success of the organization depends on the goodwill and sanity of those in control. (6). The great aim of the association must be to maintain standards, and to discuss problems, not individuals.

The task of organization and adoption of a constitution was next undertaken. The committee proposed that the name of the association should be the American Association of University Professors. An amendment was offered to the effect that the name should be the American Association of University and College Professors, but the amendment was lost. It was argued that the name proposed in the amendment was too long and cumbersome. But the convincing argument was that the name suggested by the amendment obscured the real purpose of the committee, namely, that the great criterion of membership in the association should be recognized scholarship, and that one of the primary objects of the association should be the encouragement of scholarship.

The liveliest discussion of the whole meeting was concerned with the question of eligibility to membership in the association. The sense of the meeting was first ascertained upon two general matters connected with this big topic. It was decided that the membership should be individual, and not by institution. In the debate it was pointed out that many American scholars of national, or even of international, reputation, had always been connected with comparatively small institutions, and such men as these should have the opportunity of becoming allied with this association, but they might be excluded if the association should decide that institutions below a certain arbitrarily fixed grade, or a certain size, should be excluded. A second vote was to the effect that eligibility should be "limited to persons of standing or value in teaching or scientific production." When these two general matters were settled, the specific terms of eligibility for membership were debated. The proposal was made that only those should be eligible who held the rank of professor, and had held a teaching or research position for at least ten years. There were really two points at issue in the debate. The first was connected with the problem of what should be the proper size of the association. If it became very large, concerted action would be almost impossible, and a decision ostensibly emanating from the organization might actually be the decision of a small fraction of the total membership. The second point had reference to the degree of authority or recognition which would result from decisions of the association. The argument was offered that the average age at which instructors in higher institutions begin their work of instruction is twenty-seven, and these needed at least ten years of experience before their opinions would be accepted. Further, since those with small experience greatly outnumber those with greater experience, a vote of the association might in reality represent the opinion of only the younger men, who could carry their views against the older men. The result of the debate was a vote that only those were eligible to membership who had at least ten years of experience in teaching. After this decision was reached, the question arose as to whether a still further qualification should be set. The mover of the whole matter had proposed that membership should be limited to those who held the rank of "professor." He was asked whether he meant "full professor", and he replied that he did, but had omitted the word "full", because of its possible comic connotation. This created one of the rare ripples of amusement in the session. The same arguments were again used, but one new one was offered. One speaker maintained that rank was dependent on the will of a body outside the professorial ranks, and should not be recognized in this association. A somewhat more moderate statement was that mere rank was not evidence of superiority; that lower rank in one institution might mean more than higher rank in another. Finally the whole matter of title was rejected, and it was decided that membership should be open to all those who were approved by the council, whose action in each case should depend on the successful experience and recognized scholarship of the applicant for membership.

Continuing the discussion of eligibility, much attention was given to a clause in the proposals of the organizing committee, to the effect that no person should be eligible for membership whose principal occupation was not that of education or research, and no administrative officer who did not give a substantial amount of instruction. This is, of course, only an elaborate method of excluding presidents and deans. The conservative and trustful man thought that faculties needed the help of presidents, and presidents needed the help of faculties in determining upon the proper methods of appointment and promotion, and in settling problems of administration. Therefore, presidents should not only be eligible, but should be invited to become members. Others. still moderate, thought that the presence of presidents would prove embarrassing t0 a free discussion of these topics, and that the presidents would themselves prefer to be absent. The extreme wing on the other side wished presidents ipsofacto to be excluded. One speaker predicted that if presidents were at the meeting they would be found in the acts of handshaking and distribution of cigars, in order to sway opinion. After much discussion it was voted that presidents should be excluded, unless they qualified in the same manner as others. The same vote was taken in reference to deans; but the debate elicited the information that the functions of deans, and the method of their appointment differ decidedly in different institutions; and yet deans is deans, and not professors.

After a settlement of the terms of eligibility to membership was reached, the adoption of the remainder of the constitution was comparatively easy. The various articles were discussed, and a provisional wording voted, with the understanding that the council should be charged with the duty of making such verbal changes as might be deemed necessary. The constitution as adopted was in the spirit of the original circular sent out by the committee, and only one point need be mentioned particularly. The council was to have power to appoint committees for the investigation of various topics in which the association was interested, and of special matters that might arise. This was meant to include alleged violation of academic freedom in any specific instance, dismissals from faculties without adequate causes assigned, and other similar circumstances that seemed to demand immediate attention.

Lastly came suggestions as to suitable subjects for investigation or discussion during the current year. Many suggestions were made by individuals, and these need not be given here. But the following were voiced by several, or by a considerable number, and indications are that they will soon be taken up. (1). Methods of appointment and promotion. (2). Present methods of recruiting faculties, with special reference to fellowships and scholarships. (3). Central stenographic bureaus. (4). Academic freedom. (5). Relation of faculties to the government of universities. (6). Tenure of professorial rank. (7). Means whereby time for research may be conserved. (8). Relation of instruction to research. (9). Inter-university co-operation to avoid duplication. (10). The Carnegie Foundation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOXFORD IN WAR TIME

February 1915 By Conrad E. Snow '12 -

Article

ArticleGERMANY AT WAR

February 1915 By Max Mueller -

Books

BooksThe Life of Thomas Brackett Reed

February 1915 By CHARLES R. LINGLEY -

Class Notes

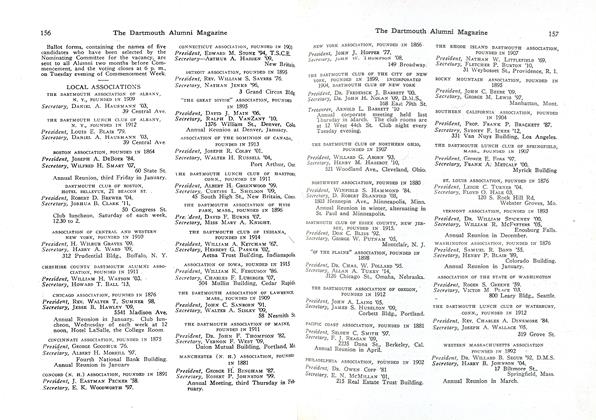

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

February 1915 -

Article

ArticleThe recently published Dartmouth

February 1915 -

Article

ArticleTHE HOLY LAND OF ASIA MINOR

February 1915 By FRANCIS E. CLARK 1873

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN CHINA REPORTS CONTINUED PROGRESS

August, 1926 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Takes Second in Magazine Competition

MARCH 1930 -

Article

ArticleComposers in Residence Named for the Summer

JANUARY 1969 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

Winter 1993 -

Article

ArticleConfessions of a Former White House Intern

APRIL 1998 By Monica Oberkofler -

Article

ArticleThe FBI Asked Him To Help Find Him

June 1976 By W.H. FERRY