by SAMUEL W. MCCALL 1874 pp. V II+303 . 26 illustrations. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, Mass., 1914

When Thomas B. Reed was elected speaker of the House of Representatives in December, 1889, he faced complications for the settlement of which he was better equipped than any other public man in the country. The republicans were in the majority, but by so small a margin that, under ordinary circumstances, a quorum could not be obtained without the aid of the democrats. The readiness of a minority to hamper legislation by dilatory tactics is as well known as it is natural,—witness the opponents of the Kansas-Nebraska bill alternating the motion to adjourn and to set a day to adjourn no fewer than 128 times, to impede the passage of that famous measure. The crisis came soon. It was one to which Mr. Reed had looked forward and for which he was prepared. On a certain day in January, 1890, 163 members were present and voting, while 165 constituted a quorum. Enough democrats were present in the body to make the required number, and to spare. Down went the precedents of years when the calm and bulky speaker drawled, "The Chair directs the clerk to record the names of the following members present and refusing to vote." He then proceeded to name a number of democrats present but not responding to the roll-call. A quorum was thus made and business could go on. Traditions of the Uproar in the House have come down to our own day. The storm rose and fell and raged again about the imperturbable speaker, to no avail. The decision stood and business went on throughout the session whenever a quorum was present, whether the members chose to vote or not. Furthermore, the same method of stopping parliamentary filibustering was adopted at a later time by the democratic party and has been one of the recognized precedents for most of the time since.

The incident is, perhaps, the climax of the life of Speaker Reed as Congressman McCall tells it. Thomas B. Reed was born in Maine, in 1839. He attended Bowdoin College, and as a lad was attracted to the republican party at its birth. After a brief political and legal career in his native state, he found himself elected to the national House of Representatives, of which he remained a member until the close of the Spanish War. Having, on principle, opposed the war, the annexation of Hawaii and the acquisition of the Philippines, he determined to retire from public life. Referring to the taking of the Philippines, he said: "I have tried, perhaps not always successfully, to make the acts of my public life accord with my conscience, and I cannot now do this thing." By far the greater part of the book is, naturally, taken up with a generally chronological account of Reed's work in the House of Representatives. This necessitates a brief summary of manv of the political events of the years 1877-1899. After his retirement he practiced law for a time in New York City.

In several respects the book is a most interesting and valuable biography. Mr. McCall has had rare opportunities for reaching source materials, having had access to the family papers, as well as to the aid of Mr. Reed's close friend, Mr. Asher Hinds. The author's own service in congress and his experience in writing biography has increased his equipment for the task. The book is interesting, more so, the reviewer feels, than Mr. McCall's life of Thaddeus Stevens. Would that the life of many another great figure of the last forty years, notably Mr. Cleveland, might be written with similar sympathetic insight and access to the family papers!

The paraphernalia of foot-note references and bibliography is missing,— more is the pity—following the example of the American Statesmen series. Again,—to finish our bill of complaints as soon as possible,—the account of the climax of Mr. Reed's career is not full enough, at least for the needs of the student of recent history. Four important changes were made in parliamentary procedure as the result of Mr. Reed's speakership, all with a view to expediting legislation. Only, that concerning counting a quorum, the one mentioned above, is here discussed. Some other parts of the story, particularly the retirement of Mr. Reed, deserve greater detail. The picture of the speaker, just re-elected to the House by a decisive vote, certain to be chosen to preside again, but retiring completely from public life for conscience sake, is an attractive one. Anyone interested in history and national affairs would certainly welcome a fuller account of the reasons which actuated Mr. Reed and the struggle thought which he doubtless went in making his decision.

Mr. McCall has wisely told what Mr. Reed was, without trying to magnify him to proportions which would make him unrecognizable. Mr. Reed was a constructive parliamentarian, not a great maker of legislation. He invented machinery that turned out a finished product. The raw material was furnished by someone else. His natural endowments fitted him exactly for the important role of chief, of. the machinery of legislation in the House. His wit.—he saw humor in everything,-enabled him to puncture the blatant and out-sting the sarcastic into good behavior. In a campaign of personalities, Mr. McCall aptly says, Mr. Reed was "at no disadvantage." His dominating bulk and imperturbable serenity, added to his well-stocked and nimble mind, his long service in the House and his acquaintance with its ways, completed his equipment.

The period of Mr. Reed's activity was one which sadly needed a parliamentarian of the Reed type. During the '80's and early '90's neither party had control of the executive and both branches of congress at the same time for consecutive periods long enough to make possible constructive legislation on great topics. On some great subjects, notably finance, even the leaders wobbled woefully; on others, such as civil service reform, parties were not united or consistent; and on still others, like the tariff, the country made-up 'and unmade-up its mind at frequent intervals. Hence the history of parties in the House during this time is composed of a series of skirmishes and pitched battles. In such an arena one who could control the elements and keep the wheels in motion performed a much needed task. That was the great work of Thomas Brackett Reed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOXFORD IN WAR TIME

February 1915 By Conrad E. Snow '12 -

Article

ArticleTHE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY PROFESSORS

February 1915 By Richard W. Husband -

Article

ArticleGERMANY AT WAR

February 1915 By Max Mueller -

Class Notes

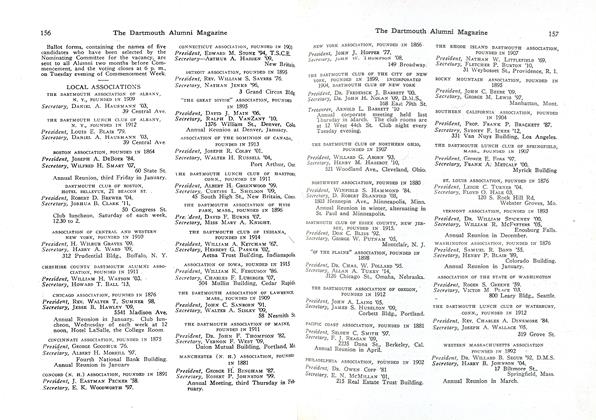

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

February 1915 -

Article

ArticleThe recently published Dartmouth

February 1915 -

Article

ArticleTHE HOLY LAND OF ASIA MINOR

February 1915 By FRANCIS E. CLARK 1873

CHARLES R. LINGLEY

-

Article

ArticleSALMON P. CHASE, UNDERGRADUATE AND PEDAGOGUE

October 1919 By Charles R. Lingley -

Books

BooksMemories of Many Men in Many Lands

June, 1923 By CHARLES R. LINGLEY -

Article

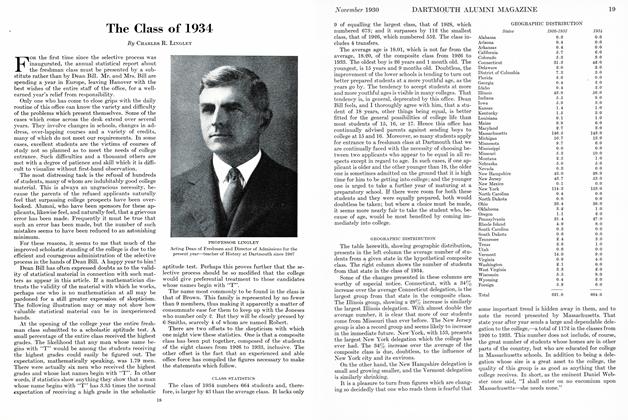

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November, 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Books

BooksWILLIAM HOWARD TAFT

January, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleSome Misapprehensions in Regard to the Selective Process

February, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleRichardson's New History of the College*

MAY 1932 By Charles R. Lingley

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE JADE NECKLACE OF LIN SAN KWEI.

MARCH 1959 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Books

BooksTHE DEFENSE OF FREEDOM

October 1941 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksSeparate, Unequal

April 1981 By Kenneth Libo '59 -

Books

BooksA Good Yarn

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Mary B.Ross -

Books

BooksBASIC SOURCES OF THE JUDAEO-CHRISTIAN TRADITION.

NOVEMBER 1962 By ROY B. CHAMBERLIN -

Books

BooksTHE TEACHING OF ENGLISH: AVOWALS AND VENTURES

JUNE, 1928 By Stearns Morse