It seems probable that the first point at which we shall be called upon to define our attitude is on the contention that all education, to be worth while, must be made more utilitarian. One finds generally in the English periodicals of the present the argument that classical education is a luxury which has outlived any possible usefulness, and which must go the way of all those other luxuries which have been foregone; and that new obligations and responsibilities can only be met by an education of which every branch shall be designed for direct application to immediate needs. Likewise, there come back to us accounts of meetings of groups? of German schoolmasters in the trenches, for instance, where resolutions are adopted to the effect that when the war shall be over these teachers will return to their homes with determination to make the German system of education more practical. These occurrences cannot be dismissed as sporadic. The evidence abounds that the national tendencies in these great nations is in the direction of an educational system of pure utility.

No tribute is fitting, for none is needed, to those institutions of higher learning in our country which have been founded for, and are giving, the vita| training of a highly specialized technical curriculum. They have merited, and won, the highest commendation. The liberal colleges, with all other types of educational institution, owe the technical schools a great debt of gratitude for their insistence upon the scientific method in the approach to scholarship, which has had its effect throughout the educational world. We are a widespread people, with numberless needs, and we could not do without that which such types of education have afforded. The realm of higher education, however, is of too great area for any kind of institution to occupy it all, and least of any should the traditional cultural college have ambition to attempt it. The funcion of the cultural college has proved to be of the utmost importance; its work has been of distinctive service throughout the nation's history; and its future success, in my opinion, will be more marked,- if change is to be made, - by reverting to a curriculum of fewer subjects better taught, than by spreading its efforts constantly thinner until its attitude takes on unfortunate semblance to a sprawl.

if is not likely to be, at any time, that without loss to itself the world can close its mind to the influences of the past. The intuitions for the beautiful and the understanding of the logical which have come down to us from civilizations which have risen and lived their allotted lives are foundations for that appreciation of philosophy, art and literature without which the world would lose its breadth and depth.

There has been no better expression of this belief than is included in the "Memorandum on the Limitations of Scientific Education," issued by. a group of Englishmen of world-wide fame, headed by Lord Bryce, and published as a protest against the prevalent propaganda for the monopolization of the field of education in England by technical subjects:

"It is of the utmost importance that our higher education should not become materialistic through too narrow a regard for practical efficiency. Technical knowledge is essential to our industrial prosperity and national safety; but education should be nothing less than a preparation for the whole of life. It should introduce the future citizens of the community not merely to the physical structure of the world in which they live but also to the deeper interests and problems of politics, thought and human life. It should acquaint them, so far as may be, with the capacities and ideals of mankind, as expressed in literature and in art, with its ambitions and achievements as recorded in history, and with the nature and laws of the world as interpreted by science, philosophy and religion. * * * Some of its most distinguished representatives have strongly insisted that early specialization is injurious to the interests they have at heart, and that the best preparation for scientific pursuits is a general, training which includes some study of language, literature and history. Such a training gives width of view and flexibility of intellect. Industry and commerce will be most successfully pursued by men whose education has stimulated their imagination and widened their sympathies.

" * * * What we want is scientific method in all the branches of an education which will develop human faculty and the power of thinking clearly to the highest possible degree.

"In this education we believe that the study of Greece and Rome must always have a large part, because our whole civilization is rooted in the history of these peoples, and without knowledge of them can not be properly understood." ;

I am emphasizing certain convictions about the older humanities, not from any lack of confidence and belief in the sciences, but simply because the sciences will not be subject to attack in the newer movements in education as will be the humanities. And in regard to those essential subjects of the curriculum which we know as the newer humanities, it is simply to be said that they will be open to much the same sort of attack as has been the older group once the agitation against this latter shall prove successful.

There is no law of physical science to which more exact analogy can be found in the realm of movements social, economic, philosophical or religious, than that which states action and reaction to be equal and opposite in direction. As one studies the swing of theory from one extreme to another in mental and spiritual realms, he comes to the understanding that the influence of the college on these must be a steadying influence, like the force of gravity on the pendulum, tending constantly to shorten the arc of motion and influencing toward an eventual stable equilibrium. It is for this reason that the college cannot be inherently either radical or conservative, for the same principle which impels it to pull back from one extreme today will tomorrow lead it to endeavor to correct the overswing of the reaction.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe last public acts of the Reverend Francis Brown

November 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

November 1916 By Conrad E. Snow -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

November 1916 By Conrad E. Snow -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

November 1916 By Conrad E. Snow -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1916 By Sturgis Pishon -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1916 By Sturgis Pishon

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE DIARY OF WILLIAM SMITH OF CAYENDISH, VERMONT, A FRESHMAN IN DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, SEPT. 23, 1822-AUG. 3, 1823

January, 1911 -

Article

ArticleGraduate Fellowships

May 1939 -

Article

ArticleLAURELS

June 1989 -

Article

ArticleVox in the Box

JANUARY 1998 -

Article

ArticleCROSS COUNTRY AND SOCCER

OCTOBER 1964 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

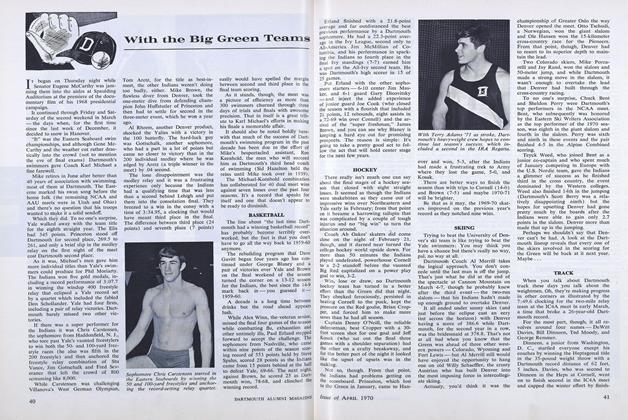

ArticleTRACK

APRIL 1970 By JACK DEGANGE