On the fifth of last March, President Nichols and I, representing the College at the Montpelier Alumni Dinner, were guests in Mr. DeBoer's home. After the dinner we sat for a while chatting in the library. Among other matters DeBoer spoke of the great business of which he was the head. "We publish , he said, "the statement that in the last twelve years (the period of his presidency), of more than ninety-nine millions of investments we have not lost a cent of principal or interest'. He paused, then went on with a smile, "They say in the large centers of finance, that is a lie on the face of it, and I think we shall do as well not to publish that statement in future, but," he added with the emphasis of his strong voice, "it is true all the same". That was the man, — proud, first, not of what he had achieved, nor of the money he was earning for himself, but of the soundness of the trust with which he was charged.

He was foreign born, poor, at seven unable to speak a word of English. He became a noble American citizen, powerful but not self-seeking; he pushed up through to eminence and financial comfort as naturally as a sprouting acorn lifts the pebbles above it, but without developing the thorns and spikes of the aggressive self-made man; when he reached college he had acquired an odd mastery of classic English, to which he opportunely added colloquial tongues, so that his public speech was delightful in its accurate playfulness, or sometimes crushing in its power.

In the first rank of great men of business he was always the scholar. He may have had disadvantage in the necessity of working his way in college, but he came out fourth in a brilliant class. He taught; he was superintendent of schools; for many years he was the scientific brains behind the business —the actuary—of a great developing insurance company; he loved to quote the masters of his adopted tongue; and he was one of the few modern citizens who delighted in a large, mouth-filling Latin phrase.

Men naturally turned to him for the headship of affairs. He was president of his company; he was the last president of the Boston Alumni Association; he declined the offer of a princely salary to take the management of one of the largest insurance companies in the world—ten times his own salary or more; he was frequently proposed for the governorship of his state, and could have been elected at any time when he chose to be an active candidate. Many who knew him well spoke of him for that high office the presidency of the college of his constant love and intimacy.

Possibly there were times when his sturdiness went over into brusqueness; I do not know. On occasion he may have wielded a hammer; I hope so; many things need to be cracked, or smashed, or pounded into shape, or driven in.

DeBoer was a great man,—great by reason of his force, his cultivated ability, his broad grasp of the principles of things, his high ideals, his personal charm' his noble integrity. Those who knew him best were surest of his greatness. By the simple and natural process of being himself he had already come into the light in his own state, among the men of his college, and in his business. He was a recognized first citizen, a pre-eminent alumnus, a master organizer and executive. But after all he was only midway in the career open to the rare men of his type and degree.

To eyes that are not blind there is something shining, splendid, in the upbuilding and maintenance of any great business organization in which the aim is complete soundness and excellence; and which is held by its up-builders and managers as a trust for those who have invested in it, for those who work for it, and for those who use its product. A great factory, a widely branching railroad, a distributing market,—each in this manner almost acquires a beneficent personality. Such administrators are, I suppose, more common than our gloomy suspicions or our collectors of startling news permit us to believe. Here at any rate, was one, a Dartmouth man in every drop of his blood, whose sensitive pride and honor were wholly enlisted in maintaining the soundness of the complex business, upon which so many depended. We must not let his example be lost or his memory grow dim.

EDWIN J. BARTLETT

JOSEPH AREND DEBOER

DISTINGUISHED MEMBERS LOST TO THE CLASS OF 1884

WINFIELD SCOTT HAMMOND

DISTINGUISHED MEMBERS LOST TO THE CLASS OF 1884

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

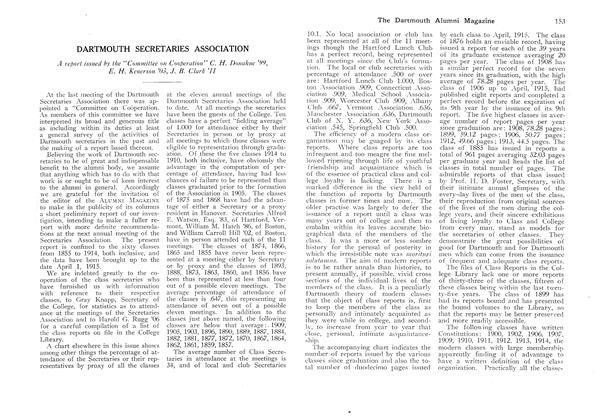

ArticleDARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

February 1916 -

Article

ArticleRICHARD NELVILLE HALL '15

February 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1884

February 1916 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AND THE SECONDARY SCHOOLS

February 1916 By James L. McConanghy -

Class Notes

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

February 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1861

February 1916

Article

-

Article

ArticleROLLINS CHAPEL REMODELED

February 1917 -

Article

ArticleSTEELE CHEMISTRY BUILDING FORMALLY DEDICATED OCT. 29

December 1921 -

Article

ArticleLARGE CLASSES AND SMALL

February 1934 -

Article

ArticleAdams Collection

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleThe College

April 1974 -

Article

ArticleThe Anti-Doctor Doctor

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93