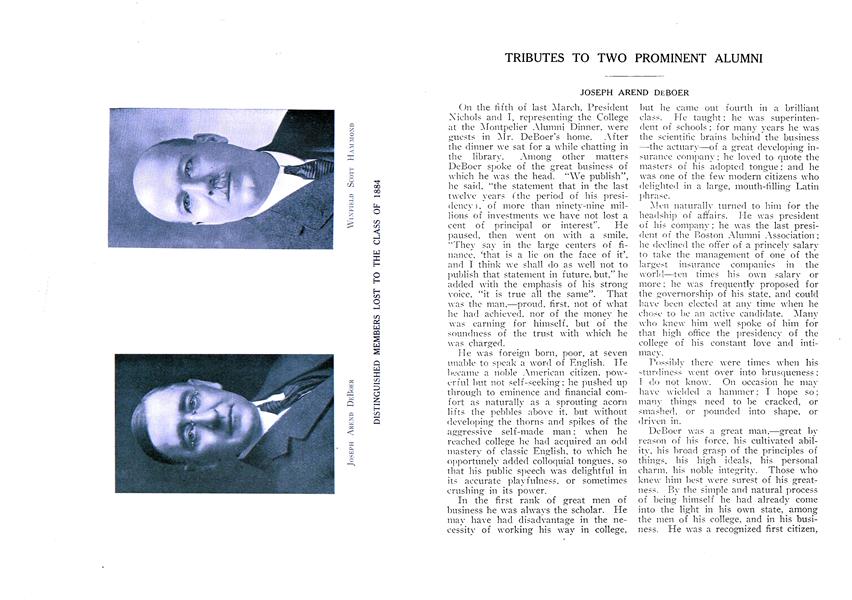

In writing of the late Governor Hammond, I shall perforce speak in a personal and intimate way, for I knew him only as a personal friend. Soon after graduation the tides of circumstance drifted us far apart, and yet the few years during which we were together sufficiently proved the unusual quality of his personality.

There was a charm in it which I have encountered in no other man. It escapes analysis or definition, but the few who knew him well were thoroughly alive to it.

Now that he has fallen, in the heyday of his manhood and of his achievement, I should like to set down, in brief, the more salient qualities which even in those early years marked him as a man of exceptional promise.

And first, he was a modest man. No student at Dartmouth in his day was less obtrusive or less covetous of popularity. I doubt if anyone in the class of '84 could have picked him out as the man who would attain the most conspicuous position. But as we look back upon it all we can see that it was in him. He stood, as it were, in the background, an observer of men, a keen critic of their motives and their actions.

In the second place, his intimacies were intellectual rather than of the heart. They were based on judgment rather than impulse. He never was a good partisan. He told me that he was elected to Congress by the combined votes of Democrats and Republicans. Soon after his election to the governorship of Minnesota, I was assured by leading men in that state that he was carried into office on a surprisingly nonpartisan vote. This is precisely what was to have been expected. It was the moderation and sanity of his views rather than any unreasoning personal fealty on the part of his friends which lifted him to that important post. To some this might, and doubtless did, seem cold, but it was the nature of the man.

In the third place, he knew what he wanted. No man in college selected from the curriculum the particular and definite articles of his intellectual diet with greater fastidiousness than Hammond. He concentrated on these, and he let the others go with an apparent lack of appreciation that may have shocked some of his instructors.

I shall not soon forget the night when, soon after our return from teaching school on the Cape, we foregathered in his room and together faced the dismal fact that on the morrow we must appear before our Professor in Philosophy and "make up" certain hundreds of pages of the history of that delectable science. What we did not do to Spinoza, Kant, Hegel and Hume that night would be scarce worth doing. I can see now the kindly twinkle in Hammond's eye when he charged me with complete mental vacuity as touching the Idea of Plato; which awkward thrust I could parry only by ironical references to his own tenuous hold upon the Categorical Imperative.

When, however, it came to such a subject as Constitutional Law, Hammond demonstrated the seriousness of his purpose and vindicated his power of sane selection. He sniffed the battle from afar and took the bits in his teeth. He cared little for "marks" in those days. He made his later.

And lastly, he was a man who set no little goals. Beneath the mildness of his exterior and the apparent indifference of his manner one could suspect an immense ambition. The meek shall inherit the earth but he wanted his not as a bequest but as an achievement. He was in a fair way to secure whatever he was after. At the moment of his demise he was in line for the highest position in the gift of his countrymen. The qualities that had carried him so far must assuredly have carried him to the highest positions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

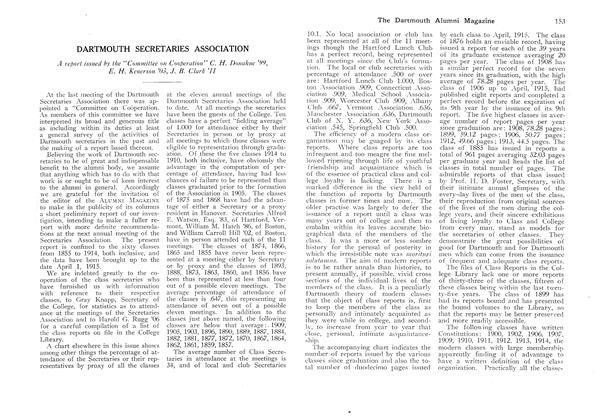

ArticleDARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

February 1916 -

Article

ArticleRICHARD NELVILLE HALL '15

February 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1884

February 1916 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AND THE SECONDARY SCHOOLS

February 1916 By James L. McConanghy -

Class Notes

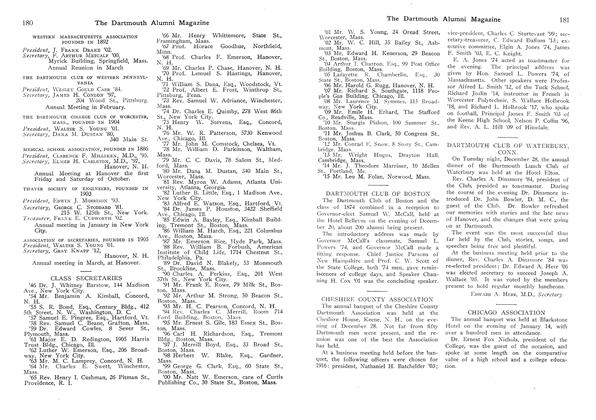

Class NotesLOCAL ASSOCIATIONS

February 1916 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1861

February 1916