A radical departure from established custom was marked at the last annual public meeting of the Academie Francaise when two American citizens — Mr. and Mrs. Edward Tuck—were awarded a "Prix de Vertu."

The famous French institute, the "40 Immortals," which thus honors an American name, though now in the fourth century of its existence, is still a living force in French life and letters. Membership of the body is one of the most coveted distinctions among Frenchmen, and if its usages and ceremonial retain an old-world savour, they are interpreted in the) spirit of our own age.

The Academy grew out of small informal meetings held in Paris towards the end of the 16th century, whose interests were mainly literary and philosophical. They, met to discuss poetry and eloquence. How Richelieu incorporated them in 1635 "for the cultivation of the French language and literature," and how later they coalesced with other learned bodies to form the Institut de France, are matters of general knowledge.

One of the means adopted to promote the object of the Academy was the bestowal of prizes on the authors of poetical and oratorical compositions selected as the best of the year. To provide funds for prizes many legacies or donations were made to the Academy during the eighteenth century. It was in 1782 that an anonymous donor established a prize to be awarded by the Academy "for some virtuous action, which shall be commended in an oration to be delivered by the Director in public assembly; the subject of the encomium to be some laudable action done in the city of Paris or in its surrounding." The prize could be divided, and honorable mention might be made of other virtuous acts which, without having obtained a prize, were considered worthy of being brought to public attention.

At the annual meeting of December, 1916, a Swiss institution, The International Committee of the Red Cross, and two Americans, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Tuck, were named the first among authors of virtuous actions which the Academy desired to honor with a prize.

The International' Red Crabs Committee. whose headquarters are at Geneva, have since August, 1914, maintained communication between members of families separated by the war. It employs 1200 citizens of Geneva, men and women. It receives 1500 to 2000 letters of enquiry daily, and sends out 3000 to 4000. Up to the end of 1915 it had arranged the transport of nearly 16,000,000 packages of food, clothing and other comforts to prisoners of war, deported civilians and others in need. The whole enterprise is admirably managed and works with almost clock-like precision.

M. Emile Lavasse, the Directeur (which is the title of the presiding officer of the Académie) in presenting the next two laureates to his colleagues, said:

"Mr. and Mrs. Tuck, Americans, for whom France is a second and well-be-loved mother-country. Before the war they had heaped the town of Rueil with their benefactions, among which is a fine hospital with an endowed annual income of 70,000 francs. A School of Domestic Economy, founded by Mrs. Tuck, has for the present been transformed into an ambulance. They have multiplied their gifts to other ambulances and hospitals. These are fine examples of the sympathy of the United States for France, a sympathy made manifest by munificent charity, and by the numerous adhesions to our righteous cause. I think of these solemn declarations as of judgments, by which men of high eminence, knowing the spirit of France and the spirit of Germany. knowing our civilization and their kultur, have notified Germany that she has forever fallen from her pretensions to intellectual leadership."

Addressing the recipients of the prize, M. Frederick Masson, whose published works include a history of the Academy, says:

"Contrary to its established usage, the Academy this year for the first time has crowned a foreign society and a foreigner — the International Committee of the Red Cross, and you. The joining of your names will not displease you, for you know the noble work that Society is accomplishing. You, for thirty years in our country, have done good, without ostentation, without advertisement, without seeking honors, solely for the sake of doing good. When I first knew you, I was impressed by what I was told of your works of charity a Rueil and in Paris. Since then I have followed attentively your admirable career, and it was a great pleasure to me to bring it to the notice of my fellow-Academicians. We know what a friend you have been to France and to the French, not only in these latter days when we ought to have on our side all who wish to be free, all who would continue worthy to be called men, but also in less troubled days when you were able to appreciate both of you, the beauty of the sky of this our lie de France. Before presenting your names to the Academy I thought it my duty to consult the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who gave his immediate, warm and decided approval. My colleagues accepted the proposal unanimously, for they could not better than through you honor our friends on the other side of the Atlantic."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

April 1917 By Eugene D. Towler '17, W. J. TUCKER. -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE MONTH

April 1917 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S MILITARY POLICY

April 1917 -

Article

ArticleDue to a fancied isolation,

April 1917 -

Article

ArticleMARCH MEETING OF THE TRUSTEES

April 1917 -

Article

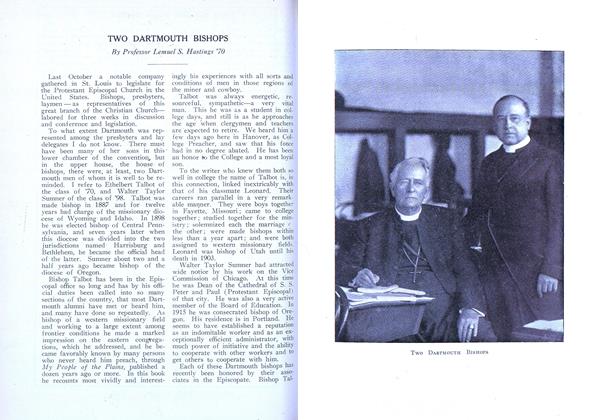

ArticleTWO DARTMOUTH BISHOPS

April 1917 By Lemuel S. Hastings '70

Article

-

Article

ArticleTuck Graduation

June 1929 -

Article

ArticleVisiting Professor

JULY 1959 -

Article

ArticleForeign Clubs Visited

FEBRUARY 1966 -

Article

ArticleSignal-Caller for the Hurt

October 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleSAMSON OCCOM, A PICTURESQUE DIARIST

JANUARY, 1928 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

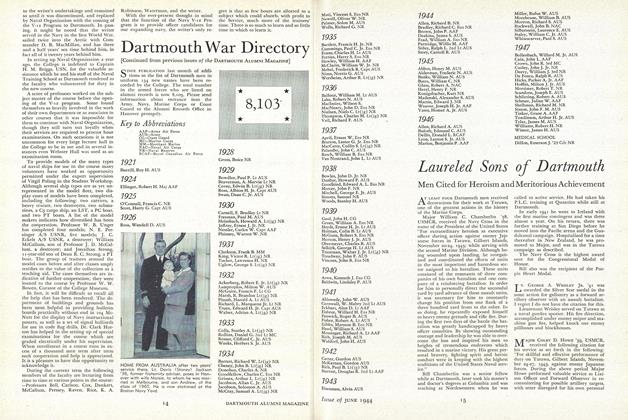

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1944 By H. F. W.