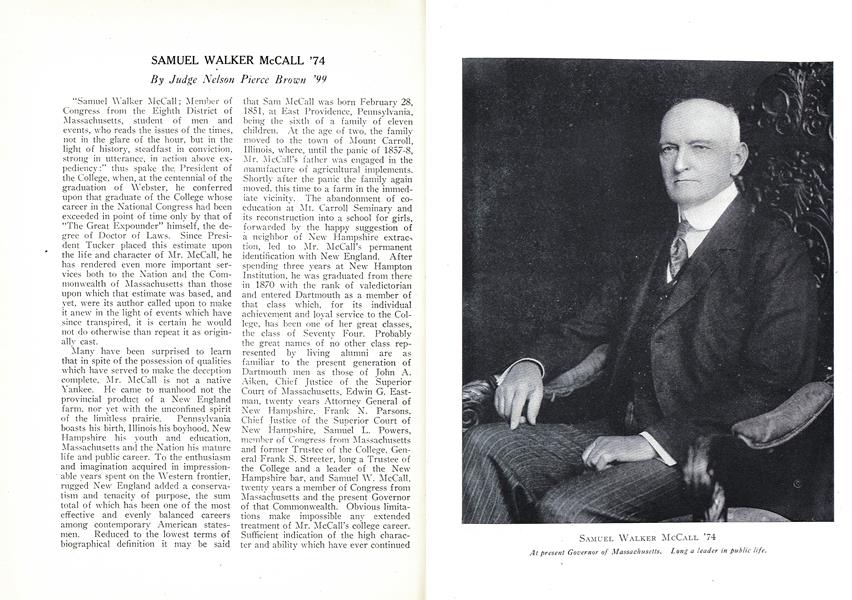

"Samuel Walker McCall; Member of Congress from the Eighth District of Massachusetts, student of men and events, who reads the issues of the times, not in the glare of the hour, but in the light of history, steadfast in conviction, strong in utterance, in action above expediency thus spake the, President of the College, when, at the centennial of the graduation of Webster, he conferred upon that graduate of the College whose career in the National Congress had been exceeded in point of time only by that of "The Great Expounder" himself, the degree of Doctor of Laws. Since President Tucker placed this estimate upon the life and character of Mr. McCall, he has rendered even more important services both to the Nation and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts than those upon which that estimate was based, and yet, were its author called upon to make it anew in the light of events which have since transpired, it is certain he would not do otherwise than repeat it as originally cast.

Many have been surprised to learn that in spite of the possession of qualities which have served to make the deception complete, Mr. McCall is not a native Yankee. He came to manhood not the provincial product of a New England farm, nor yet with the unconfined spirit of the limitless prairie, Pennsylvania boasts his birth, Illinois his boyhood, New Hampshire his youth and education, Massachusetts and the Nation his mature life and public career. To the enthusiasm and imagination acquired in impressionable years spent on the Western frontier, rugged New England added a conservatism and tenacity of purpose, the sum total of which has been one of the most effective and evenly balanced careers among contemporary American statesmen. Reduced to the lowest terms of biographical definition it may be said that Sam McCall was born February 28, 1851, at East Providence, Pennsylvania, being the sixth of a family of eleven children. At the age of two. the family moved to the town of Mount Carroll, Illinois, where, until the panic of 1857-8, Mr. McCall's father was engaged in the manufacture of agricultural implements. Shortly after the panic the family again moved, this time to a farm in the immediate vicinity. The abandonment of coeducation at Mt. Carroll Seminary and its reconstruction into a school for girls, forwarded by the happy suggestion of a neighbor of New Hampshire extraction, led to Mr. McCall's permanent identification with New England. After spending three years at New Hampton Institution, he was graduated from there in 1870 with the rank of valedictorian and entered Dartmouth as a member of that class which, for its individual achievement and loyal service to the College, has been one of her great classes, the class of Seventy Four. Probably the great names of no other class represented by living alumni are as familiar to the present generation of Dartmouth men as those of John A. Aiken, Chief Justice of the Superior Court of Massachusetts, Edwin G. Eastman, twenty years Attorney General of New Hampshire, Frank N. Parsons, Chief Justice of the Superior Court of New Hampshire, Samuel L. Powers, member of Congress from Massachusetts and former Trustee of the College, General Frank S. Streeter, long a Trustee of the College and a leader of the New Hampshire bar, and Samuel W. McCall, twenty years a member of Congress from Massachusetts and the present Governor of that Commonwealth. Obvious limitations make impossible any extended treatment of Mr. McCall's college career. Sufficient indication of the high character and ability which have ever continued to distinguish his public service is to be found in his editorship of "The Anvil," a publication of more than ordinary merit, his selection as instructor in the Classics in Kimball Union Academy, and his winning, without severe extension, the second highest rank in the Phi Beta Kappa delegation from his class.

It was but natural that an aptitude and love for debate, an exceptional classical scholarship, and an intense and active interest in public affairs should have led him to enter the legal profession. Although enjoying the most congenial association with his classmate Powers both in the study and, immediately following his admission to the bar, in the practice of law, his natural inclinations and peculiar qualifications for a public career soon led to his abandonment of active practice. Although not coincident with his entrance into public life, the story of the division of partnership property by Powers taking the copy of the Public Statutes and McCall the copy of Webster's dictionary has become one of the Dartmouth classics.

His first official contact with legislative affairs came with his election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1887. Although a "first year man," he received immediate recognition-through his appointment to the chairmanship of the important Committee on Probate and Insolvency. Far from being satisfied with the perfunctory service rendered by the average maiden legislator, he showed no hesitation in exerting what proved to be a powerful and intelligent influence upon the work of the session. Like the air fighter of the present war who is instructed "not to wait for a fight, but to pick one," so this new recruit in the army of reform did not wait for opportunity to call upon him, but went forth seeking it. was he slow in finding it. Here in his first year of membership in a legislative body, he mani- fested that broad and sympathetic understanding of human nature, its hopes and aspirations, and that keen sensitiveness to injustice, which have ever been conspicuous features of his character. It was due to his efforts during this year that there was written upon the statute books of Massachusetts a just poor debtor law, free from the hardships and inequalities of a system which bore all too many marks of feudal oppression, by the terms of which enactment the atrocious fee system, and imprisonment for debt except in cases of fraud, were permanently abolished.

A year intervened before he again returned to the legislature, but as chair man of the Committee on Judiciary he became the titular leader of the lower branch and achieved the distinction through his introduction of what was known at the time as "The Anti-Boodle Bill," and the preparation on behalf of the Judiciary Committee of a report and resolution defining the position of the House in its controversy with the Supreme Judicial Court over the latter's refusal to answer a request for its opinion. The quality of this report first directed attention to McCall's ability as a constitutional lawyer. During his last year in the legislature in 1892 he had the satisfaction of seeing the "Anti-Boodle Bill" made into law, and thus, to use the language of his biographer, Mr. Evans, achieved "the distinction of leading the way, both in the legislation of Massachusetts and in the Federal Congress, in the enactment of legislation having for its object the restriction and regulation of the use of money in elections."

With the year 1892 came his first nomination as a member of Congress from the eighth district. It was no perfunctory contest to which the Republicans of the eighth district called him. The district was a close one politically. The Democratic candidate, John F. Andrew, not only because of the traditional popularity of his illustrious father, the "War Governor" of the Commonwealth, but also because of the great personal popularity of the candidate himself, was an extremely dangerous opponent. The election of a Republican of long service in high position would have been considered an exceptional victory, but for Mr. McCall it can justly be claimed to have been an especial recognition of the esteem in which he was already held by what has been regarded as the most particular and demanding constituency among the Congressional districts of the Commonwealth. Although the district was carried by the Democratic candidate for Governor by 52 votes, Mr. McCall was returned a winner by a majority of 992. The constantly increasing satisfaction with which he continued to serve it during the two decades he was destined to remain in Congress is best attested by the fact that during the other nine contests, he was every time nominated by his party by acclamation, and easily elected; at one election having been returned with a majority of 18,888 votes, the largest majority ever received by a candidate for Congress in Massachusetts. Incidentally, it has been a source of no little satisfaction to Dartmouth men that this district, so permeated with the culture and influence of Harvard University should have been represented for so long, and with such conspicuous brilliancy by a graduate of the College.

Fie now belonged to the country. A staunch believer in a republican form of government and a close constitutional student, he well understood he was not a mere delegate to record the will and carry out the instructions of his immediate constituency. From the moment he took his seat, he became a Representative to the fullest meaning of which the word is capable. His career, as evidenced both by his recorded speeches and votes, showed an independence not only of constituent, but of party control where great principles were involved, which was refreshing during a period when it seemed as if the judgment and action of Congress had been delegated to a few. In "his own words addressed to his constituents upon his retirement from Con- gress, "I have always felt that the best recompense I could make for your generous support was to reverence our relations as your Representative, and treat your commission broadly as a mandate to serve the whole country."

It was but typical of the man that when, during the Spanish War, a resolution was introduced in a Republican caucus in his district expressing its disapproval of his disinclination to respond to the whip then being snapped rather vigorously by Rep. Grosvenor of Ohio, he should have replied, "if you are looking for a man to represent you as Grosvenor says, if you want a man with the back bone of an angleworm, don't send me back to Congress." Needless to say, the resolution was defeated and thereby the seal of disapprobation put upon the proposition so strongly favored by some political bosses that the ideal Representative to Congress should be an invertebrate.

That a new member should be seen and not heard was a principle to which Mr. McCall gave the same measure of respect in Congress he had given in the Massachusetts legislature. Taking his seat August 5, 1893, at the special session called by President Cleveland for the repeal of the Silver Purchase Act of 1890, during one of the severest financial crises in the history of the country, he immediately plunged into the active debate of that intricate question in support of the President's policy. So deep was the favorable impression made by his efforts, both upon the floor of the House and in the forum of the nation, that not only did it receive wide public and press recognition, but when three years later the country seemed about to adopt Mr. Bryan's free silver theories, he was called upon to bear an important share of the burden of stemming the tide in those Middle and Western States where those fetiches had acquired a most dangerous popularity. The reputation which he thus early established as a sound student and master of. the problems of national finance he never ceased to maintain, and that too during a period of our history which, was not only of itself prolific of financial hysteria and heresy, but to which was added the complication of a war with a European power.

While the tendency toward specialization had not respected even the halls of legislation, and men were there achieving preeminence in narrow fields, Mr. McCall's well balanced powers made him equally at home in the consideration of broad questions of constitutional rights and duties as well as those others which, like finance and tariff, involved not only sound judgment, but painstaking attention to detail. When he chose to speak it was with a thorough mastery of his subject and of the most forcible means of expressing the ideas he wished to convey. His simple but virile diction,, no less apparent in his public speeches than in his literary productions the result-of direct thinking and highly cultivated power of expression made him a leader in every debate in which he chose to participate. He easily justified the characterization of the New York Sun after his speech in 1906 upon revision of the tariff as "perhaps the most intellectual man in the House, and without a doubt the most independent."

Although actively connected with many important reforms or attempts at reform in various fields of government, his attitude never was that of the reformer pure and simple with its frequent loss of effectiveness, but rather that of the intelligent politician who fights for the whole, but never refuses the half when the whole is unattainable. At the same time, he never has been of that class of politicians who would prefer to pick the lock of the back door than enter freely at the front, nor of those who would tolerate compromise where great principles were involved.

As a member of the great Committee upon Ways and Means from 1899 to 1913, he rendered service in connection with such important matters as reciprocal trade relations with Cuba, the Payne tariff act, and reciprocity with Canada, not excelled by that of any other member of'the House' In fact, at the request of President Taft, he introduced and had charge of the passage through House of the act for Canadian reciprocity which only failed of complete success through its rejection by Canada herself, a rejection for which the propaganda of hostile American interests has been held largely responsible.

At a time when the country was inflamed by what was then, and even now still remains, an unproved fact, the alleged implication of Spain in the sinking of the Maine, he; was one of six members who refused their approval to the declaration of war with that country. It was to be expected of a judicial temperament that refused to form a judgment upon ex parte testimony or to be swayed from its true course by popular clamor; but when the country was once committed to the war, he loyally and vigorously supported every measure designed to prosecute it to a successful conclusion.

Believing the permanent acquisition of the Philippine Islands would but add to race problems, of which the country seemed to have a surfeit, that it deprived the Monroe Doctrine of all consistent excuse for existence, and was in violation of the spirit and letter of that great Charter of our liberties, the Declaration of Independence, he was one of the most consistent and effective opponents of the policy of "Imperialism". Massachusetts, at least, will never fail to give full credit to the patriotism and ablity with which Mr. Hoar in the Senate and Mr. McCall in the House contended almost single handed against what they believed to be a radical and unjustifiable departure from the fundamental princples of our liberties.

His Congressional career was marked by a distinct loyalty to the Constitution, a belief in a rational tariff, absolute justice to our conquered provinces, and strict economy in public expenditures. As a member of the Committee on Elections, and for two years its chairman, he saw its entire fourteen reports, including some adverse to his own party's interest, accepted by the House in every instance. He served upon nearly every committee appointed by the House for the investigation of its own members, m itself a bestowal of confidence on the part of his colleagues in which he might feel a just pride. His ten years of service on the Committee on the Library made it possible for him to put his interest in and appreciation of the arts and sciences to a practical use which has done much toward the beautifying of our National Capital, while his present service on the Lincoln Memorial Commission assures to it the addition of one of the most impressive memorials of the world.

His thorough familiarity with governmental systems in general and the American Constitution in particular made him a leader in .every debate involving a constitutional questions. His contribution to these debates have left a permanent impress. The House has had no more able or jealous opponent of the frequent attempts on the part of the Senate to infringe upon its constitutional prerogatives. His vigorous opposition to the threatened amendment of the Constitution "by construction" in limitation of the power of the states, to the power to abrogate treaties by vote of the Senate alone, to the proposed amendment to provide for an income tax, to the initiative, referendum, and recall, and his advocacy of the autonomy of the states, the proposed amendment to provide for uniform labor laws, and the popular election of Senators were conducted upon the highest plane of-constitutional discussion, while his speeches and contributed articles upon those important measures have earned rank with the efforts of the earlier masters in that field. No reproach has ever been uttered against the motives of any of his public acts. No one ever presumed to question that the purpose constantly guiding his conduct was, to use his own words, "to help keep vital the essential principles of the American Constitution so necessary to the continued greatness of our country and to the preservation of our liberties."

Coincident with Mr. McCall's retirement from Congress came the retirement of Hon. Winthrop Murray Crane from the Senate. Mr. McCall immediately announced his candidacy for Mr. Crane's seat. There was a strong public sentiment that Mr. McCall was the logical successor. Not only his long and distinguished service in the lower branch, but also the possession of an ideal equipment, perhaps on the whole better adapted even to the atmosphere of the Senate than to the House, was quickly appreciated by the people and gave a strong impetus to his candidacy. From the press of the entire country came expressions of approval and confidence that Massachusetts was about to honor herself and the nation by adding another worthy name to an already illustrious succession. But the popular election of United States Senators was not yet a fact. The peculiar demands of an election by the legislature had to be met. The issue was complicated by a variety of motives and personal expediency, as a result of which, after leading the ballot for three days and coming within a few votes of the nomination, on the third day, hovering fortune lighted on the standard of his opponent.

But while the Legislature refused to make him Senator, Massachusetts soon called him to what history may record as a greater service than that denied him. For five years, mainly by reason of the Progressive defection from the Republican party, a defection due, in Massachusetts at least, fully as much to a disapproval of the methods by which certain leaders assumed to control its destinies as to an approval of so-called Progressive principles, the Democratic party had elected its candidate for Governor. The Republican division seemed almost hopeless. But after one unsuccessful attempt to persuade him from Ins Winchester retirement. Mr. McCall finally consented to take the nomination. Although unsuccessful in his first campaign in 1914, he increased the Republican vote by over 80,000, and in 1915 by nearly 120,000 over the vote cast in 1913, in the latter year defeating one of the most popular Governors the Commonwealth had ever had.

Probably no other man could have achieved this result. No doubt many candidates could make as honest assurances to the errant Progressives, but Mr. McCall's well known independence of control, his freedom from the sinister influences against which their defection was a protest, constituted a sufficient guaranty that an end of the old regime was in sight. This confidence outweighed even Mr. McCall's well known hostility to some of the pet reforms to which they had committed themselves in their wanderings. By increased majorities he was re-elected in 1916 and 1917, and with the advent of the United States into the great European war, has taken his place among the "War Governors" of his Commonwealth. Nor is this title a perfunctory one, for true to her traditions, during his incumbency, Massa- chusetts troops were the first on the Mexican border and first to assist in discharging America's obligaton to stricken France.

But Mr. McCall does not need the glory of being a "War Governor" to entitle him to a place among the great Governors of Massachusetts. With characteristic directness, he immediately set about reorganizing the work of the government by attacking the multiplicity of commissions, reducing expenditures to terms of reasonable economy, and materially assisting in a wholesale reduction of the state tax. He advocated and promoted the calling of a Constitutional Convention, still in session, a portion of whose important work has already been written into fundamental law. Through his foresight and administrative capacity a great machine for the promotion of the public safety was created which quickly became the model upon which similar organizations in other states have been built. And withal, his innate sense of justice and hatred of oppression have found opportunity for expression in a brilliant veto of an attempt again to throttle the will of the people by a return to the discredited method of nominating state officers by convention, and in the dignified but firm refusal to make Massachusetts a party to the persecution of the poor negro at the hands of Southern prejudice. Nor should it be forgotten that in spite of the prominence of her graduates in the political history of Massachusetts, it remained for him to achieve the distinction of being the first Dartmouth Governor of the Commonwealth.

And yet, had Mr. McCall never entered public life, his accomplishments in the field of literature have been of sufficient merit to earn him a permanent place among American men of letters. His biographies of Thaddeus Stevens and Thomas B. Reed constitute most valuable contributions to the history of American statesmen. His "Business of Congress," comprising lectures delivered at Columbia, and his "Liberty of Citizenship," comprising the Dodge lectures delivered at Yale, easily take first rank in their respective fields, while his oration upon Webster, delivered at the centennial, belongs no less to the country than to Dartmouth.

Proud as Dartmouth would have been to know him as her President, his refusal of her brightest honor, regretted at the time, has resulted in bringing to her and to him probably greater credit even than could his acceptance. His letter, declining the presidency is worthy of a permanent place among Dartmouth letters. With Stevens and Webster and Choate he already has carried her banner with honor upon the field of great affairs, he has demonstrated to American life the ruggedness and virility of her training and" instruction, he has returned to her lap not only the talent she gave him, but others added to it. What glory he may add to her name only the future can disclose.

SAMUEL WALKER MCCALL '74 At present Governor of Massachusetts. Long a leader in public life.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

December 1939 -

Article

ArticleNaval Openings

December 1941 -

Article

ArticleNative patterns

MAY • 1987 -

Article

ArticleCANOE DROPOUT

Jan/Feb 2006 By Bill Gifford '88 -

Article

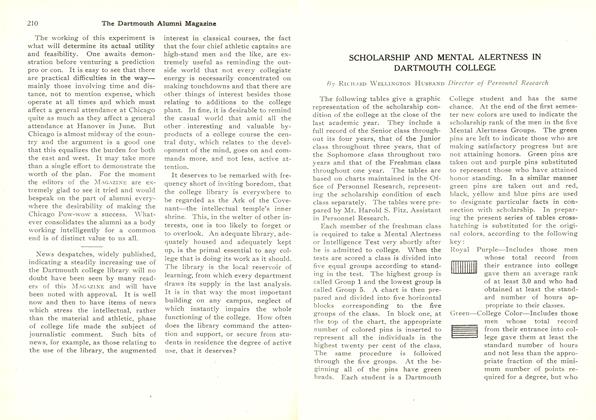

ArticleSCHOLARSHIP AND MENTAL ALERTNESS IN DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SCHOLARSHIP AND MENTAL ALERTNESS IN DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

January 1924 By Richard Wellington Husband -

Article

ArticleTHE UNOFFICIAL AMBASSADOR TO FRANCE

AUGUST, 1928 By Robert Davis '03