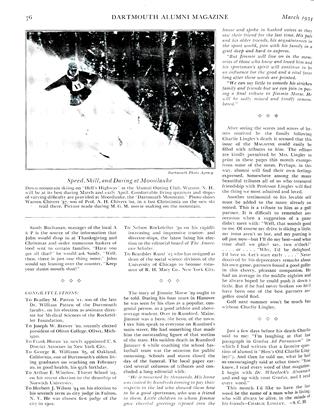

The following letter has been received by the editor from C. D. Horton '15. Mr Horton went to France in 1916 as a ski-man in Red Cross work. He soon changed to aviation and has since been busy acquiring experience and honor in the flying branch of the French Army.

Plessis-Belleville, May 16, 1918.

Please excuse the many I's with which I shall be forced to propel this narrative. Since I last wrote you, about a year ago, I've been to the front and been sent back to the rear, and now I'm trained again for different work. I had about nine months of reconnaissance flying, which is the most interesting job of all. Here one works at fairly low altitudes, and sees a great deal of the war. You see the reciprocal bombardment from a seat in the orchestra, and generally you lead the music at the same time. Artillery reglage is the nicest, especially when you start on a fresh target, such as a clean cement fort, or a newly fortified trench. Often the same pilot and the same observer will work for several days on the target. This is only so when the target does not have to be destroyed immediately. You sail out in the earliest dawn and get pretty close to your fort. Someone's been doing something to it, for it doesn't look as new as it did when you left it the night before, after three hours' hammering. The Boches have been covering it over with earth. The roof of the fort, which is a machine gun emplacement, is perhaps six feet under ground. It was discovered by a microscopic study of photographs. 1 he first work done on it was the unlevying of the two yards of earth which buried it. This tegument was easily brushed off with a reglage of fifty 75 centimeter shells. The white cement was exposed and ready for the heavies, the 120 s and the 210's. These seem to have chipped the framework in spots, but before the firing is started again by the whole battery, send a couple of single 210's to see if this new cover of earth is too deep. In a few minutes a fat 210 sends up a puff of smoke and spray into the air (this is in soggy, boggy, foggy Flanders), and presently the white cement is again exposed. The heavy firing can continue, five minutes to regulate each gun separately, and soon the heavies begin to work steadily by fours. The plane is working steadily, too, over the target to mark the shot, back to the battery to get the ground signals and to correct the fire, then back to the target, and so on for two or even three hours. Flying only half a mile high, the battlefield is a wide yellow gash, belting the earth from Dunkirk to Ypres, where it is hidden by the mist. The battery below is the only external sound, except the roaring of the two motors, thump, thump, thump, thump! And it is felt rather than heard, for the sound wave makes a plane "jump" at the same time. Occasionally a passing shell gives the craft a nasty knock. A big fellow lining us 50 yards away gives the plane a slow uplift and drop, as a sluggsh swell on the sea. A little 75, coming nearer, gives a puny, but very swift jolt. When the motion is particularly pronounced, the observer turns around, and we exchange glances, as if to say "That one came near!" These are our own shells, too, possibly from the very battery we're directing, and therein lies one of the chief dangers of the work. In Flanders last summer and fall, the Allied attack necessitated great artillery preparation, and the air was full of menace for our observing planes. But the work goes on, for this fort must be made useless for planting machine guns. At the end of two and one-half hours the battery spreads out its white "goodbye" signal. They have their guns regulated now so that they can fire the rest of the day without our aid. Work is over. But we still have gasoline left for another hour, so let's take a joy ride. I have a machine which can be converted into a double command 'bus by screwing, in a steel control bar. This bar is for the observer in case the pilot is "hors de combat."

But few observers know how to handle a-machine and they're all anxious to learn. There's a good-natured jealousy between the pilots and the observers. The pilot is the observer's "taxi-driver"; the observer is the pilot's "bundle." Also, we say, "An observer is an officer who wants to be a pilot." And no wonder! You can't blame an observer for wanting to know how to save his life. My favorite observer knew how to drive a machine in the air because of these little joy rides. I'd take the machine high enough so that I could catch it if he let it slip, and he'd. screw in his stick and take control, and I, myself, would enjoy the scenery in my turn. We'd go over the sea at Dunkirk, skirt the beach, and have machine gun practice on the dunes. My big bi-motor carried gasoline enough for four hours' flight, but after three and one-half hours we generally were tired.

I could tell of camera raids and how we helped the infantry attacks, but these would take too long. Instead, I'll tell of my only fight, and how the enemy flier escaped from me. In reconnaissance we generally fly so low that we re out of danger from the fighting machines two or three miles above us, as long as we keep our eyes open. But one busy day, just as we were opening shop and regulating four batteries at once, the always expected enemy appeared. He was flying alone on our side of the canal, which' was contrary to custom and wisdom. As our work at the moment was important, I did nothing more than to keep my eye on him. My observer, how ever, became suddenly excited, unslung his Hotchkiss gun, and bade me give chase. The enemy was not a biplane, like us, but much smaller and faster, and what the Hindenburg was he doing there! He was circling and mounting. He certainly saw us, and several other Allied planes near us, but he did not offer battle. After him we went, and he persisted in his upward spiral. On the curves, I found that I could turn and make as much headway as he, but I couldn't keep my height. Finally I managed to jockey the 'bus within fifty yards of his tail, and the Hotchkiss started to stutter. My observer was a good shot, but the swift foe seemed untouched. He continued to climb, and on the last steep curve I lost him. He headed for Bochie and disappeared. My observer made a gesture of resigned mortification. I did not appear to share his thoughts, so he wrote a few words on his map-board and passed it to me. And not till then did I understand. "It was a carrier' pigeon." What's the use of regretting? I'd done my best to get the "enemy flier," solely out of respect for my observer's sporting instinct, and that's half of the 'impulse in any part of the air game.

I have left reconnaissance work now, and am training for monoplane work, but I know that nothing will happen to me on a fighting machine that can compare in interest with life on my slow and steady passenger 'bus. I regret this change because no more will I share the thrills of a vigorous bombardment, or a gas attack. No more will I pore over new-made photographs with a magnifying glass.to see whether the battery of minnen-werfers has been obliterated by our work. No more wrill I rejoice to see the cocards on our own fighting machines swooping over my head and keeping away the Albatross, the Roland, and the latest Fokker. Instead, I shall be one of these policemen of the air myself. I shall be flying too high to see the batteries in action, and the only danger will be from others of my kind.

Every man likes his own job best. You can guess that reconnaissance strongly appealed to me. But listen to the other men. The daytime bomber says, "No siree. Nothing else for me. We go right out and we come right back, after having dropped our 'crottes' and there's enough of us here to keep off the Boches. What, the shell fire? Oh yes, there is some of that, but they never hit us. Night bombing? Not for me! Break your neck when you land!"

Then the night bomber: "Night bombing's the best job of all. Shell fire doesn't count at night, and they can't chase us in their machines, and it's lots of fun. Safest job in the business. Are the fogs dangerous? Nothing much. We lose a man now and then who has to land in a fog, but a good pilot generally gets backall right."

Lastly, the "chasse" pilot, the hunter and fighter: "Of course, you know, we're the elite of the air, and we don't have to carry any observer to tell us what to do. It's a great job—not like flying a slow bi-motor, where the Boches can pounce right on you and bowl you over. We can take care of ourselves, and of the others, too. You ask if we don't lose a lot of men? Yes, we do, but they are the young pilots who've never been over the lines before. The first Boche they see they go for him, regardless of his position or armament, and they get eaten up. But after a chasse-pilot's lasted two months, it's his own fault if he gets brought down."

I dare say I shall like "chasse" work as well as the reconnaissance. It required a commandant's recommendation to allow me to change over, so it is a gift not to be refused, for it's hard to change after one is well broken in for special work. I've now enough experience to save me from most of the stupid possibilities of the air. I haven't "ramassed" any medals yet, but I have four beautiful decorations, which are something of a tribute to my ability. These four much-to-be-desired decorations are "mes quatres pattes." May I long continue to bear them!