This comment appeared in the columns of the New York Evening Post:

“It is, sir, as I have said, a small college.” If Webster could have attended the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the institution which he saved from becoming in name at least, a university, he would have found that while it is still a college, it is no longer small. Indeed, during his own student days, Dartmouth was not the tiny place that it is apt to be imagined as being. His famous words give one a picture of a little bit of a college overshadowed by the mighty establishments of Harvard, Yale and Prince- ton. Yet in the decade in which his Ife at Dartmouth fell, his “small college” graduated more students than Yale or Princeton, and not many fewer than the oldest of them all, Har- vard. This rank it was not destined to retain, although it clung closely to Princeton for more than half a century. It is not surprising, there- fore, that in the celebration at Hanover noth- ing was heard of the question so eagerly dis- cussed a few years ago, of the place of the small college. There are small colleges, but Dartmouth is not of them. Her members and guests spoke of her simply as “the college.”

Dartmouth is larger than Brown; she is larger than any one of a dozen of our State universities. And she is bound to be larger. Her 1500 students of pre-war days, like the similar number at Tufts and Oberlin, will soon be left far behind. It is an exceptional college that is not having a record-breaking enrolment this fall. One of the problems of the small college then, is how to remain small. Cynically minded persons have questioned whether there was any small college that had this ambition. They have pointed to adver- tisements of such institutions and asked why a college should seek more students on the ground that it was a small college. Even col- leges that have not advertised have been un- able to stop growing. In vain Amherst makes Greek compulsory. It is hard to find a well- known “small college” with fewer than 400 students. Dickinson has 500, Lafayette and Williams 600, Mount Holyoke 800, and Vas- sar 1200. William and Mary has managed to keep down to 250 and Hamilton to 200. For the bulk of the really small colleges, however, it is necessary to turn to the denominational colleges, for which that is the more accurate designation. Some states, like Ohio, are flooded with them. Although they draw to some extent upon the community in which they are located, their growth is in the main conditioned by that of the church which they represent, and this, as a rule, means slow de- velopment, both in numbers and in endow- ment.

The “small college” of a few years ago has changed in more than numbers. Even when it has not grown beyond recognition, it has ac- quired a more formal method of procedure. President Emeritus Tucker, whose volume of reminiscences, entitled “My Generation,” has appeared just as the college of which he was the head from 1893-1909 has been rejoicing in its century and a half of progress, gives a picture of his entrance at Dartmouth in 1857 that might have been duplicated for a long time thereafter in a multitude of colleges, but that the smallest would now hardly be able to reproduce:

“I recall very clearly my examination for college. It was made up of a succession of individual, oral interviews, conducted by the professors in charge, in their private studies. A certain fluency in reading from one or two of the prescribed Latin authors brought from Professor Sanborn, who was little inclined to waste any unnecessary time in so tedious a business, the abrupt but pleasing remark— ‘Well, there is no use in eating a joint of mut- ton to tell whether it’s tainted or not.’ . . .

The examination in mathematics brought me to the study of Prof. ,Ira Young—father of the celebrated astronomer—just before the dinner hour. ,1 had hardly been seated and put to work upori a problem, before the dining-room door opened and dinner announced, itself. After a little the professor asked me how long it would take me to finish my work. I replied (truthfully) that I couldn’t tell. He quickly made his own calculation, asked me a few general questions, and closed the interview. The alternative was evidently a cold—a very cold—dinner.”

In some respects the college has gone far in imitating the university. It is a very small college, indeed, that cannot muster up enough assurance to offer an LL.D. to President, King, or Cardinal. Yet the largest colleges feel closer to the smaller ones than to universities of their own size. One admires his univer- sity; he loves his college. Or if this does not do the university man justice, let the thing be looked at from the other end. The uni- versity stands primarily for scholarship; the college, in President Wilson’s words at the inauguration of President Nichols at Dart- mouth in 1909, for “a passion ... a pas- sion not so much individual as social, a pas- sion for the things which live, for the things which enlighten, for the things which bind men together in unselfish companies.” The small college, especially if it be isolated, is obviously hampered in this undertaking. It tends to develop intensity at the expense of breadth. But here too it has been changing. Not a few of the really small colleges may ap- ply to themselves Mr. Tucker’s story of the director of a small railroad who wanted to connect it with the New York Central. To the rather contemptuous question of Commo- dore Vanderbilt, “How long is your little road?” he replied, “What does that matter? It’s just as wide as yours is.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE SESQUI-CENTENNIAL

December 1919 By George Levi Kibbee -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH COLLEGE: AN ATTEMPT AT FORMAL INTERPRETATION

December 1919 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF TRUSTEES MEETING

December 1919 -

Article

ArticleNEW ENGLAND STATES

December 1919 -

Article

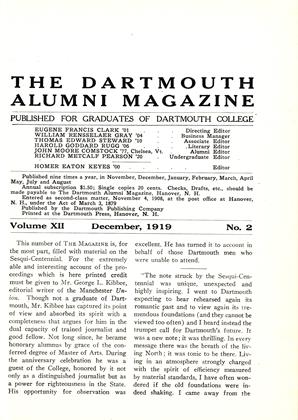

ArticleThis number of The Magazine

December 1919 -

Article

ArticleFALL MEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1919 By Homer E. Keyes