ADDRESS OF PRESIDENT ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS AT THE OPENING OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, SEPTEMBER 23, 1920

November 1920ADDRESS OF PRESIDENT ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS AT THE OPENING OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, SEPTEMBER 23, 1920 November 1920

Dartmouth College today begins its 152nd year with unprecedented enrollment, —larger than anticipated even a few months ago.; far smaller than what was available to it. The number of applications for admission, however, is not in itself of large consequence but its significance lies in the faith in the College which is thus bespoken. We must not allow .ourselves to forget that confidence so proffered in the purpose of the College is deserved simply to the degree that fundamentally the College is actuated by a clean-cut intelligent sense of spiritual motive and civic responsibility and to the extent that individually each of us is conscious of personal accountability to assist in making this purpose effective.

The vitality of the College is dependent upon realization and understanding of the obligation which rests upon it and upon the extent to which the obligation is met. The whole situation is a challenge to us collectively and individually and no man in the group here, whether by election to official position or by enrollment in undergraduate membership, is exempt from the responsibility imposed that the answer to this challenge shall be adequate.

A generation is the custodian of the civilization of its time and is eventually adjudged to have been worthy or unworthy according to whether it transmits to the future a civilization richer or poorer than was received in things which make for collective welfare and individual satisfaction. The civilization of a given period is the code of society of that time. Society is a combination of individuals. Thus we arrive at the inevitable conclusion that upon the thinking and upon the actions of each one of us is dependent the greater or lesser good of the civilization for which we are trustees .

It is an exceedingly easy thing, viewing the proposition of responsibility in its magnitude, with all its complexities, to become fatalistic in our thinking and to accept a dictum that individual effort makes no difference to society. Thus we can seek a personal alibi by the simple device of adopting a personal theory of laissez faire. Even so, nevertheless, we are not freed from the fundamental fact that the reaction from effort is essential to the individual who seeks intellectual and spiritual growth. Society, however, is made up of thinking beings. In the final analysis it cannot be considered as an inanimate machine but must be considered as a living organism,, existent because of and in behalf of the human beings who compose it. To this view education must unreservedly commit itself no less than must religion.

I make these generalizations because I wish immediately at the opening of this College year to begin to emphasize the fact of individual responsibility resting upon each man among us and to suggest the premises of the argument by which such a conclusion is justified. It is yet more necessary, however, in such a period as this for us to examine some of the extraordinary circumstances under the influence of which we are called upon to define how personal responsibility shall be assumed and what its method of expression in behalf of the public good shall be in times like these.

The blinding flare of war has paled, giving sense of relief, it is true, but leaving devastated areas of mind and soul even less capable of early restoration than is the great spread of earth's surface upon which ruin was imposed. The conflagration is subdued but the embers glow and hiss and no man knows where explosion may next take place nor what tragedy it may entail. Meanwhile, a world's physical, intellectual and spiritual redemption is dependent upon knowledge of those things which are true and adherence to the dictates of truth, at a period when truth is obscured and perverted almost beyond recovery.

As the world war, far more than any in history, reached back into every detail of human life and mobilized as never dreamed of before all forces of material existence, so now the reaction reaches the remotest springs of human conduct, and galvanizes into vitality primitive instincts and selfish impulses, largely forgotten or long suppressed in deference to the code of an advancing civilization, but now, to the extent that they are endured, threatening to retard the civilization of the future and to impair the working out of democracy.

The reasons for this seem to me obviously to lie, first, in the artificiality and extraneousness of the habit of war and its customs, recently imposed of necessity upon every detail of human life; and, second, in the insistent reluctance of governments to relinquish the autocracies with which they were clothed for the special emergencies of time of war.

However unsavory the odor of the reflection now, apart from the exigencies of the struggle, the fact remains that, as it was done, breeding the morale of the people for war involved in the censorship the suppression of truth as well as of falsehood; and involved in the policy of propaganda the enthronement of part truths and emotional appeals above complete truth and the dictates of reason. These are conditions with which education is particularly concerned, for in its processes almost alone lie the correctness which make for stability and the mutual confidence which draws mankind together instead of separating it into hostile camps.

The demands of war created destructive forces powerful for their purposes when under direction but gigantic in their potentiality for harm when once they escape restraint, as evidenced in the dire distress of a prostrate empire of greatest natural resources in the world, or in the melancholy assembly of ambulances and hearses which are summoned for the relief of a stricken crowd before a Federal sub-treasury building. Intellectual indifference to the tendencies of these phenomena, whether the product of mental inertia, pessimism or cynicism', is in the last analysis a partner of the warped instinct which assumes that violence and bloodshed mark the normal or desirable avenue to peace and happiness. It is abhorrent to all for which science stands and to which true education consecrates itself.

The college today cannot stand apart from the affairs of life, if indeed it ever could. It cannot view the convulsions of the world as laboratory demonstrations in which it has no part except to observe and classify them. As a factor in the civilization of the time, the college must set itself steadfastly to stimulating the corrective processes which make for cooperation and constructive effort and healing. It must be inspired by the intellectual zeal to subordinate all else to seeking truth and must cultivate the spiritual receptivity which shall make truth recognized and followed when found. In such circumstances alone may we hope for the influences to become operative which are now so greatly needed alike in the camps of those who agitate largely for the self-indulgence and selfelation of agitation and in the citadels of those rigid minded adherents of theory which has no flexibility nor elasticity to bend to the strain of vitally changed conditions. The American college cannot view without introspective concern as to its own share in the responsibility, the melancholy fact that certain great words of the language, such as progressivism, liberalism, or idealism, properly significant of mental attitudes essential to the advance of civilization, are losing their force and even falling into disrepute because associated so constantly with groups whose theories lead but to destruction or futility. In some measure at least this is attributable to sins of omission in the process of higher education. We have not put the same stigma on mental arrogance that we have on social or political presumption. We have not withheld admiration from the man of large intellectual capacity who was too self-centered or too selfish to utilize this capacity for the benefit of society as we have withheld approval from those who hoard wealth or political power. We have not held in disdain the man who utilizes his intellectual brilliancy for irresponsible pyrotechnic display to attract the attention of an amazed populace as we would visit contempt upon the man who with like purpose splurged financially or prostituted political power.

It is a fact not without its distasteful implications that, while groups associated for almost any of the various activities of life can arrive at a policy of action founded on mutual give and take and the submerging of personal interest for the common good, measures of desirable reform and programs of social progress are almost invariably retarded and oftentimes terminated in complete futility because of the obstinacy of minds and the uncompromising attributes of temperaments in individuals whose intellectual equipment has won leadership in the movements. , It becomes increasingly plain that it must be the part of the college to compel understanding of the truth that the ineffectiveness of narrowmindedness may be as little to the ad- vantage of an age as the inability of insufficient-mindedness. Each alike is incapable of being largely useful in time of stress, and it is to the needs of such a time that we have to give attention today.

I repeat, therefore, that those of us gathered here who are solicitous for the part which Dartmouth is to play in these critical times can have but incidental interest in the exact figures of enrollment within the College. What is all-important is the number of men within this enrollment who are possessed of instinct for intelligent service to the welfare of the times in which they live and are possessed of ambition to qualify for these in attributes of mind and soul and body, in accordance with the spirit of science which is the law of humanity, which seeks to build up and not to destroy.

In 1888 at the dedication of the Institute bearing his name the veteran scientist Pasteur gave definition of the function of science which may well be cited here, so inclusive is it of the purposes for which the College wishes to stand:

"Two contrary laws seem to be wrestling with each other at the present time: the one a law of blood and death, ever devising new means of destruction and forcing nations to be constantly ready for the battlefield—the other, a law of peace, work, and health, ever developing new means of delivering man from the scourges which beset him.

"The one seeks violent conquests, the other the relief of humanity. The latter places one human life above any victory; while the former would sacrifice hundreds and thousands of lives to the ambition of one. * * * * Which of these two laws will ultimately prevail God alone knows. But we may assert that * * science will have tried, by obeying the law of humanity, to extend the frontiers of life."

May all effort within this College focus on this one great objective, to aid in extending the frontiers of life, and when the record of this great group of Dartmouth men is compiled, may this prove to have been its accomplishment!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe congestion due to the great increase in the size of the undergraduate

November 1920 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1920 By W. H EASTMAN -

Article

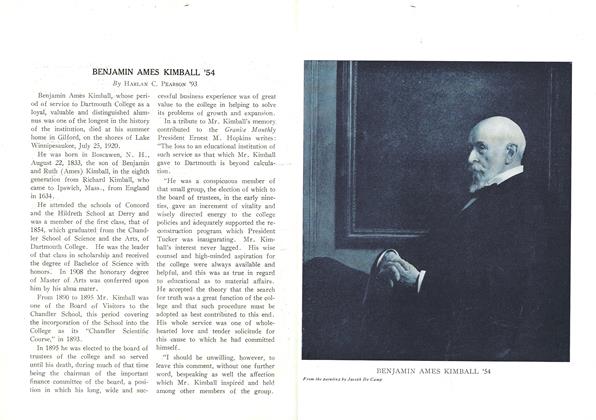

ArticleBENJAMIN AMES KIMBALL '54

November 1920 By HARLAN C. PEARSON '93 -

Class Notes

Class NotesREUNIONS CLASS OF 1870

November 1920 By A.S. ABERNETHY -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1920 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1920 By WILLIAM SEWALL