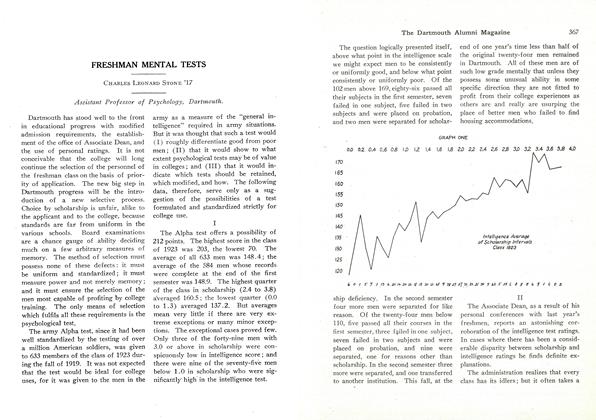

The unprecedented action of Columbia University in admitting students on the basis of an intelligence examination gave rise, not only to suggestive comment, but also to the frank doubt whether psychological tests really measure the capacity for scholarship. With this question in mind, the Department of Psychology undertook some statistical studies of the Dartmouth S. A. T. C.

In the fall of 1918 the army intelligence test, Alpha, was given to all but a few of the S. A. T. C.; and a study of the intelligence distribution by class and by state was reported in this publication last spring. Last fall the scholastic standing of each of the men tested was computed so as to represent the average scholarship through the college year 1918-1919. The present study, therefore, is a continuation of that of Mr. Echterbecker, presenting the correlation of intelligence and scholarship.

It is only fair to point out that in the case of freshmen, intelligence is correlated with only one year of scholarship; whereas, in the case of seniors, the intelligence rating is correlated for four years of scholarship. Naturally, the status of freshmen is quite unlike that of seniors, in social and mental adjustability, in elective freedom, and in purposive study. Many a man spends the major part of his first year establishing himself. The problem of financial maintenance requires relatively more of a freshman's time. Delta Alpha, various competitive try-outs, both in athletic and in non-athletic activities, vassalage to the commandeering upper classmen and the tyrannous sophomores, unceasing duties as fraternity pledges, and general familiarization with the college consume numberless hours of the freshman dial and affect scholarship undeniably. Furthermore, young Lochinvar has to learn that the college means business — and study ; and no less young Alexander the Great has to experience the humility of new worlds to conquer. It is reasonable to assume that the adjustability and establishment of added years make for a truer estimation of native scholarship.

In the measurement of intelligence no psychologist would claim a perfect instrument ; only wide experimentation and correlation will conduce to a satisfactory standard of measurement. The army test is supported by the large number of cases in which it has been used, and has at least had the benefit of an appreciable correlation with intelligent performances in national service, in schools, and in industry. A study of the relationship of intelligence to academic performance, along the suggested lines of this study, should inure to the benefit both of academic measurement and of intelligence measurement.

The army test Alpha is comprised of eight tests to measure (1) ability to follow directions; (2)ability to solve simple mathematical problems; (3) ability to make logical inferences; (4) vocabulary; (5) quickness of perception of meaning; (6) ability to perceive mathematical relationships; (7) ability to perceive concept relationships and (8) general information. The total number of items in the whole examination is 212, and a perfect performance is indicated by that number. The average of these 677 cases of the S. A. T. C. is 147.5. The average total scholarship average of these same men, through June, 1919, is 2.12 (D being represented by 1, C by 2, B by 3, and A by 4.)

The correlation of intelligence with scholarship is a positive correlation of 0.4434 (positive 1.0 indicating a perfect correlation, and zero indicating mere chance relationship).

The 24 men lowest in academic standing average 125.88 in intelligence, ranging from 88 to .167, with an average deviation of 21.53; the 25 men highest in scholarship average 172.36, ranging from 133 to 202, with an average deviation of 16.08. Of the men taken into the Phi Beta Kappa Society this fall, 15 were in the S. A. T. C. and average 177.13, ranging from 141 to 202, with an average deviation of 17.54; that is to say, judged by the army intelligence standards, every man is an A intelligence man.

Division of the S. A. T. C. into approximate quintiles shows the very significant fact that the lowest 20% in scholarship are markedly inferior in intelligence, having an average of 132.4; the highest 20% are markedly superior in intelligence, having an average of 163.9; whereas, the middle 60% in scholarship (from 1.57 to 2.63) deviate but little from one another in intelligence, the second quintile averaging 141.9, the third 148.0, and the fourth 149.2. If the relationship of scholarship to intelligence in secondary and preparatory schools shows this same accentuation at the extremes, Dartmouth's recent proposal to admit students scholastically in the upper quarter of their class in approved schools has a psychological justification in addition to that of incentive. Intelligence data could doubtlessly be secured from many of the approved schools and should prove of value to the administration. Standarized intelligence examinations for high school seniors. worked out by certain associations of colleges, state boards, or the Federal Bureau of Education, are not at all an improbability of the next few years.

That the colleges need a group examination which will better differentiate among men who in the cruder sorting of the general population are much alike, is apparent to anyone who has conjured with intelligence examination statistics; and the same need is plainly evidenced by the fact that in the Dartmouth S. A. T. C. and in most college groups about 75% of the men rate "A" (135-212).

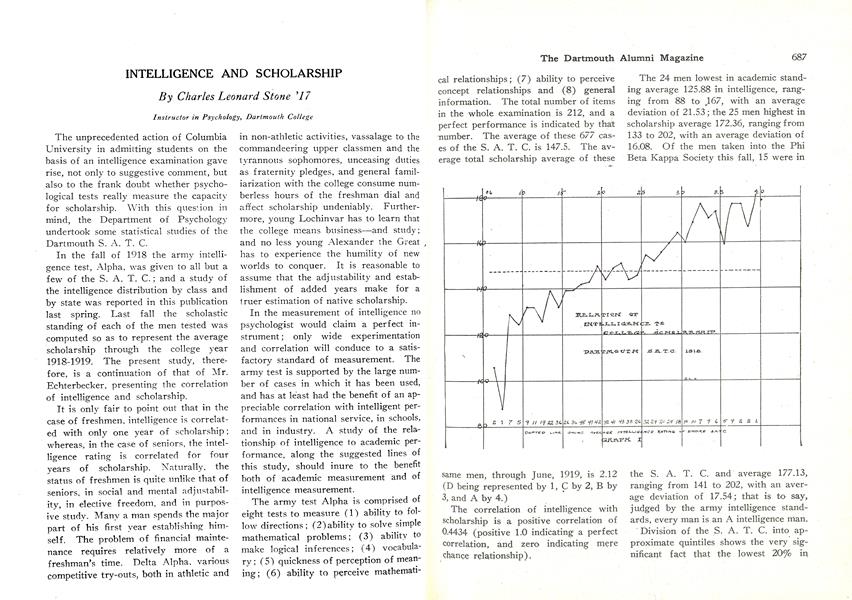

The accompanying graphs bring into relief the salient features of statistical study. Graph 1 presents the curve of relationship of intelligence to Scholarship. The points plotted are the average intelligence rating of the scholarship intervals indicated at the top of the graph. The figures at the base of the interval columns indicate the number of cases for each scholarship interval.

Graph II presents the average of special groups. Other groups, athletic, musical clubs, debating, and managerial, will be the subject of later study.

Graph III presents the average ratings of the scholarship quintiles, in which particularly the lowest and highest quintile are clearly marked off from the other groups.

Graph IV presents the percentage of men of "A" intelligence in each of the scholarship quintiles.

Study is now being made of the present freshman class to discover not only the relationship of general intelligence to general scholarship, but also the correlation of general intelligence and of specific tests of the intelligence examination with scholarship in each of the freshman studies. Such investigation will have no end of usefulness. It will be valuable to the administration to know whether men low or failing in certain subjects are indolent, overburdened with activities or extra hours, or natively incapable in those subjects. For both the students and those men consulted with regarding the selection of majors and complementary courses an additional basis for objective judgment will exist. This value alone cannot be overestimated, for much potential ability has atrophied or been perverted by the miselection of courses or aim, a problem in which students and faculty alike have floundered distressingly.

The assumption that psychological tests are infallible is, of course, as unwarranted as the belief that anyone has discovered an ideal method of rating scholarship. Our reverence for our ability to grade the scholarship of others is neither more laudable than the ambition to perfect an intelligence scale nor more logical than the hope to attain such a standard of intelligence measurement.

SAMUEL SUMNER WILDE 1789

Charles Leonard Stone '17Instructor in Psychology, Dartmouth College

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSAMUEL SUMNER WILDE 1789

March 1920 By John King Lord '68 -

Article

ArticleSTATEMENT AND COMMENT ON THE NEW ADMISSION PLAN

March 1920 -

Article

ArticleThe February issue of THE MAGAZINE came limping along

March 1920 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

March 1920 By F. L. C. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

March 1920 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Article

ArticleRESOLUTION ON SERVICES OF PROFESSORS HITCHCOCK AND HAZEN

March 1920

Charles Leonard Stone '17

-

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN MENTAL TESTS

April 1921 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Books

BooksFOUNDATIONS FOR AMERICAN EDUCATION

March 1948 By Charles Leonard Stone '17 -

Books

BooksTHE "WHY" OF MAN'S EXPERIENCE,

January 1951 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Article

ArticleEducation for What?

March 1953 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Feature

FeaturePsychology at Dartmouth

February 1958 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17

Article

-

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR JOSHI TEACHES COMPARATIVE RELIGION COURSES

MARCH, 1927 -

Article

Article'49 Alumni Fund Totals $386,611

October 1949 -

Article

Article... And a New Trustee

May 1975 -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

March 1961 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleSummer Repertory.

FEBRUARY 1966 By R.J.B. -

Article

ArticleThayer School

JUNE 1971 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29