For a better design forliving, writes . . .

PROFESSOR OF PSYCHOLOGY

DESPITE the fact that he had lived more years than any other human being, Methuselah was probably neither learned nor uniquely interested in history. Likewise the fact that I am in my thirty-sixth year as a member of the Dartmouth Faculty, and have spent eight of these years on the Committee on Educational Policy, does not, I fully realize, qualify me as an expert on education. Such length of service, however, preceded by three years as an undergraduate at Dartmouth, would almost certainly ensure anyone a varied experience* under a variety of curricula, and an acquaintance through faculty discussions, formal and informal, with a wide diversity of educational philosophies. Add to these factors in the teacher's experience the personal classroom association with some fifteen thousand students, at least ten per cent of whom are at one time or another vocal about the defects of their curriculum, and perhaps one per cent of whom on occasion wish to express a mild academic pleasure in their quadrennial sojourn on Hanover Plain, and almost any pedagogue not psychotically inhibited on second thought, perhaps especially anyone psychotically inhibited would feel a messianic urge to express the convictions of his accumulated years.

The foregoing paragraph explains in part my compulsions to go beyond the confines of my original assignment, announced in the November issue of the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE as "an article on the content and rationale of the present Dartmouth curriculum."

Although there have been many minor modifications in the Dartmouth curriculum since 1900, the only substantial revision so far in the twentieth century has been that effected in 1925 through the Committee on Educational Policy under the chairmanship of Leon Burr Richardson 'OO This revision embodied three significant changes: it enlarged the major to 30 semester-hours beyond the introductory course; it introduced a comprehensive examination in the major subject in the senior year; and it made the A.B. the sole award for completion of the undergraduate requirements, regardless of the student's major.

Although neither students nor professors felt that the academic Utopia had been achieved in this 1925 curriculum, there was no unmistakable demand for curricular re-examination prior to World War 11. The new envisagement of America and the world which was forced upon us by the attack on Pearl Harbor after we had been for several years lethargic, if somewhat disconcerted, in viewing the monstrosities of Lenin's, Mussolini's, Hitler's and Stalin's totalitarianism in Europe made most of us more realistic about the functions of education in human society. Suddenly aware that nowhere in the world had education given us an appreciation of the dignity and worth of the human individual, we hastily began to think how we might help America in the new war, for unless we helped America and other nations to defeat Italy, Germany and Japan, it seemed doubtful if there would be any dignity and worth of human beings anywhere. To be sure, utilitarian motives also entered into our efforts to keep the colleges in operation during the war. Representatives of the Armed Forces in Washington also saw advantages in keeping American colleges open, and worked out programs that would have both academic and military value. For the next few years Dartmouth with its V-12 Unit was essentially a Naval College. Although this Armed Services interlude had some unattractive characteristics, by and large most of us felt that the experience not only circumvented greater educational sacrifices and disharmonies, but actually gave us new appreciations of the meaning of education to the individual and to the nation.

In this ferment of thought committees rather generally in American colleges went to work to re-appraise the objectives, courses and methods of higher education. Among the first colleges to announce their postwar curricula, Amherst at one extreme adopted an almost entirely prescribed curriculum, and the University of Buffalo at the other extreme a curriculum of almost entirely free election. (The University of Buffalo had had such a curriculum since the First World War, and after the Second World War voted unanimously, I believe to continue this curriculum.)

AT Dartmouth Professor Richardson became the champion of the cause of free election, and proposed that except for three proficiency hurdles the student be free to choose what courses he would. Every student would be required to consult a faculty adviser in these elections, but the student would be free to make the final decisions. The three hurdles would be demonstrations of proficiency, either by examination or by the completion of courses at the level of achievement of the examination, in English, in reading a foreign language, and in American history. The Committee on Educational Policy, the membership of which was divided about evenly for and against Professor Richardson's proposal, submitted the issue to the Faculty, 75% of whom rejected the proposal. There was some slight trend of sentiment, however, in favor of a curriculum of wider freedom of election. But the overwhelming vote of the Faculty in favor of certain distributive requirements was taken by the Committee on Educational Policy, if not as a mandate, at least as an indication of the kind of curriculum the Faculty would accept and work with sympathetically.

The curriculum which emerged from two years of deliberation is described in the April, 1946, issue of the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE, pp. 16-18; and the educational philosophy behind the curriculum is enunciated in the same issue on the next two pages.

In brief, the present curriculum requires the student in his freshman and sophomore years to devote 2 semesterhours to hygiene, 12 to courses in the humanities, 12 to social sciences, 12 to the sciences, and from o to 12 semester-hours to foreign language (depending on the time after his arrival at Dartmouth when he can demonstrate proficiency in this subject). In the junior and senior years 30 hours have been required in the major subject (a requirement reduced tentatively because of the addition of ROTC courses in the present-day college) and 6 hours in Dartmouth's new educational venture, the Great Issues Course (Professor Poole's report of which appeared in last month's issue of this magazine).

The article on the philosophy behind the curriculum is perhaps summed up in one paragraph: "Dartmouth College, in our opinion, can best contribute to the future if the College is primarily and predominantly concerned with humanity rather than technology; if its educational spirit is amateur rather than professional; if its programs are planned for the student rather than for the professor; if in the operation of its curriculum it recognizes that function is more important than content; and if in its instructional procedures it stresses responsibility rather than discipline, thus making discipline a positive means to an end rather than in itself a vague and vacuous end." The article from which this paragraph is taken could be best regarded as a statement of the postulates of general education, of the principles to guide curriculum-building at such an institution as Dartmouth.

In the present article it is my intent to elaborate one of these five postulates, concerning which the April 1946 presentation stated, "It is idle to plan a content of education without giving thought to the way in which such content will function in the lives of men."

This elaboration begins, therefore, with the question, What are the objectives of education in the liberal arts college? Many answers have been given to this complex question, and obviously no answer has been or could be entirely satisfactory to everyone. Many definitions of the purpose of the college include two kinds of objectives, those concerning obligations to the student and those concerning obligations to society. Professor Richardson, for example (A Study of the Liberal College, p. 17), speaks of the student becoming "first, a better companion to himself through life, and, second, a more efficient force in his contacts with his fellow men."

A PSYCHOLOGIST is likely to consider these two objectives interrelated: those who are good companions to themselves are more likely to be effective in their social intercourse; and significant contributions to society make the contributors more companionable to themselves. No one can be a good companion to himself who is not perceptive of truth, sensitive to beauty, and devoted to virtue. These qualities in man are the source of his social worth; and his social works, in turn, further develop these qualities in him.

For the purpose of this article I should like to concentrate on man's relation to his society, as at least one aspect of the objectives in the liberal arts college. I begin with the hypothesis that the essential purpose of education is to discover, to change, and to improve one's design for living.

Thorndike opens his three-volume Educational Psychology with these two sentences: "The arts and sciences serve human welfare by helping man to change the world, including man himself, for the better. The word education refers especially to those elements of science and art which are concerned with changes in man himself." The most significant way in which we can improve the world is by improving individual men. President Dickey stated this very effectively in one of his convocation addresses: "There is nothing wrong with the world that better human beings cannot fix." The responsibility of education is the production of better human beings. Since education is in the last analysis self-education, the function of the Faculty is the catalytic one of activating in the student the perceptions, imaginations, and motivations which create in him a better design for living.

All of us in college Administration, Faculty, and students are so constantly consumed by the demands of the mechanics of education that we have neither the vitality nor the vision to keep the real objectives clearly in mind. Students whose attention is engrossed by courses, assignments, quizzes, and marks, and whose professors talk incessantly about this machinery, can hardly be vibrant to the real purpose of college. These students, therefore, accept courses as impositions which they must hurdle in order to secure the coveted sheepskin significant emblem! and in the process they formulate their own objectives, which are neither intellectual nor social, but economic and political (in the Spranger sense). In a country in which, ever since the Declaration of Independence, we have talked and thought more about rights than about responsibilities, these selfish personal aims become unwittingly a design for living, but an unsatisfactory one for a good society. This selfish, ill-conceived, immature design for living has certainly a relationship to the major maladjustments of our society mental disorder, divorce, industrial strife, crime, and war.

I do not mean to hold the liberal arts college totally responsible for these several categories of maladjustment; but I do hold the design for living responsible for most of our social ills, and the design for living is a product of all education, formal and informal especially the latter. But at least the liberal arts college should help the student to liberate himself to discover a socially sound, mature design for living.

DEMOCRACY, in my opinion, is the best form of government because, first, it is the only form of government which recognizes the dignity and worth of the individual, and, second, it demands of the individual the kind of social adjustment most likely to produce a sound and mature personality. Wherever democracy is found in the world, it is incomplete more an aspiration than an achievement. The achievement is a function of the whole educational process. In its role the liberal arts college is defective in two respects: it fails to realize that education is the education of individual human beings, and it fails to realize that formal education in college is the further development of individuals already partially educated, both formally and informally, individuals who are not only intellectual, but also emotional, human beings. One psychiatrist, Blanton, used a significant analogy when he said that "formal education is to the great mass of informal education as the visible is to the invisible part of the iceberg." If college graduates are ever to answer John Tunis' question, "Was College Worth While?" in the affirmative, the liberal arts college must be genuinely concerned with the tides and drifts of informal education; it must reach the emotions as well as the intellect; it must understand human beings in their genetic development, particularly as this genetic development determines the design for living.

Soon after we are born we are subjected to elaborate social regulations, which most of us resist initially. Some persons to whom these mores are so obnoxious as to be considered infringements on reasonable human liberty persist into adult life in rebellion against society, failing to perceive that society may sometimes adopt infelicitous means to attain quite praiseworthy ends. These chronically negative, and frequently bitter, individuals are almost certain to be badly adjusted members of our society. Other persons, although they fought social control in the beginning, yield to society, not because they realize the essential wisdom or necessity of social regulation, but because they feel themselves overwhelmed and impotent, and because conformity is easier on the nervous system especially the autonomic nervous system than the assertion of their independence. These passive individuals, although they appear superficially welladjusted, experience no real personal or social integration, and actually live little other than a vegetative existence. Blessed are those persons who discover fairly early in life that neither perennial rebellion nor absolute surrender promises either contentment or achievement. Insightfully they discover that many social ends are good and many social means faulty; that they as individuals have certain rights, but also certain responsibilities and obligations; that they must on occasion assert themselves in defiance of society, and on occasion yield to the desires and intents, if not to the opinions, of the majority. It would seem that only this third group can envision a successful design for living. At what Shelley referred to in his definition of poetry as "the best and happiest moments" of these "happiest and best minds," these persons conceive of what an ideal society would be, what kind of human beings we must be to constitute such a society, and how we can become such human beings.

As a psychologist who has long and vigorously inveighed against the glib classification of human beings into compartmental types, I am not proposing here a new trichotomy, but rather suggesting the two poles and the mean a golden mean, I believe in a certain continuum of behavioral variability. (The two poles, by the way, represent extremes of behavior which Blanton has called extreme egoadjustment and extreme group-adjustment.) The two and a quarter billion human beings who today find themselves members of some hundreds of different human cultures approximate in greater or lesser degree one of these poles or the intermediate mean.

The failure of liberal arts education, in so far as it does fail, is in part attributable to the failure of teachers to see and understand clearly their objectives or the failure to know how to achieve these objectives; but in at least as great a degree the failure results from our having our students ten to fifteen years too late to help them develop most effectively a proper design for living. Despite this enormous handicap, however, human nature even at twenty is still sufficiently modifiable for warm, patient, and imaginative teachers to guide students into more favorable patterns of adjustment.

This, as I see it, is the main purpose of the liberal arts college. If this purpose is achieved in only small degree and with even a relatively few students, and if, as a result, the incidence of mental disorder, divorce, and crime is somewhat reduced, industrial strife somewhat lessened, and war is made somewhat less probable, even this small improvement will stand as a very worthy, indeed a great, achievement.

PERHAPS at this point the reader is bothered by two perplexities, how the subject-matter o£ certain disciplines can conceivably be related to the objective proposed, and whether this design for living is something to be imposed by the Faculty or developed by the student. To answer the easier question first, no design for living can be meaningful unless it develops out of the experience of the student himself. But the teacher should so treat his subject that it provides meaningful material to fit into the design.

The other question is more difficult to answer adequately. The reader can probably see how the subject-matter of philosophy or literature, psychology or sociology would contribute to the design for living, but has some difficulty thinking how the subject-matter, say, of geology concerns this objective. To begin with, a design for living is a vaster matter than one's particular orientation to society, although in this article I have especially stressed this social adjustment as a major aspect of the design for living. Education is, in any event, considerably more than the accumulation of facts: in every course it is possible to examine the sources of knowledge, the methods by which knowledge is obtained, the uses of this knowledge for bettering human society, and the pleasures which such knowledge may afford to individual men and women. Anything less than this, it seems to me, is scholasticism pure and simple. The historian, Barnes, in his introduction to James Harvey Robinson's The Human Comedy, a book published after Robinson's death, says of the author that "he believed that human learning had little significance unless it was put directly at the service of mankind." I believe that in somewhat different language I am urging much the same thing: first, that we should not regard knowledge as an end in itself, but as a means to an end; and, second, that we should have some genuine concern socially for what end knowledge serves.

It may well be argued that the view of education presented in this article is merely the view of one psychologist; that a botanist, a geologist, a historian, a teacher of English or of a Romance language might well have a. very different view. Precisely. Life and education for it are many-faceted, and happily a college faculty has men whose life-work has emphasized varied points of view. Indeed, the present Committee on Educational Policy has representatives of the six academic departments enumerated above. A concert of such diverse voices, you may be sure, prevents any individual idiosyncrasy from throwing the group off key or from producing educational cacophony.

In conclusion, I am convinced that whoever produces new curricula, however such curricula are produced, and whether the problems are attacked centrally or peripherally, if the resultant education of the students is really improved, there will inevitably be in human society an improved design for living.

"Education is the education of individual human beings . ."

UPPERCLASSMEN REGISTER IN McNUTT HALL FOR SECOND SEMESTER COURSES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Responsibility of Management

March 1953 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Article

ArticleHome Thoughts On Europe

March 1953 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. 48 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1953 By RICHARD M. PEARSON, ROSCOE O. ELLIOTT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1953 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMOND J. MORAND III

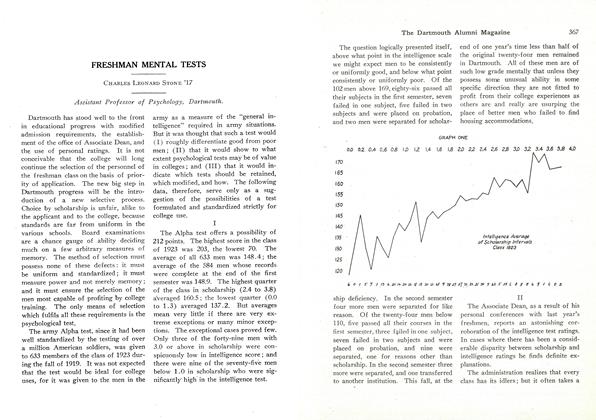

CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17

-

Article

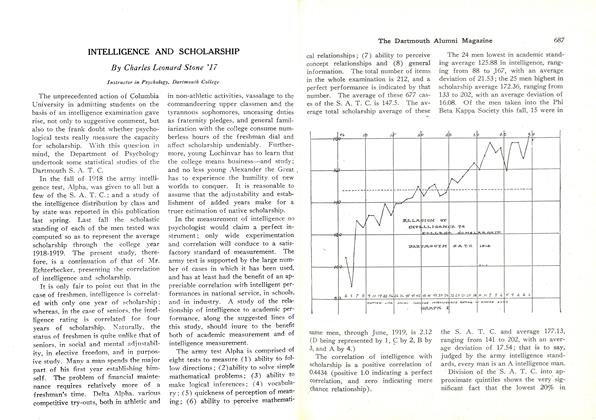

ArticleINTELLIGENCE AND SCHOLARSHIP

March 1920 By Charles Leonard Stone '17 -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN MENTAL TESTS

April 1921 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Books

BooksFOUNDATIONS FOR AMERICAN EDUCATION

March 1948 By Charles Leonard Stone '17 -

Books

BooksTHE "WHY" OF MAN'S EXPERIENCE,

January 1951 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Feature

FeaturePsychology at Dartmouth

February 1958 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17

Article

-

Article

Article21 Columbia Luncheon

October 1950 -

Article

ArticleBequests Provide $328,287

JUNE 1964 -

Article

ArticleSal Andretta Memorial

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Article

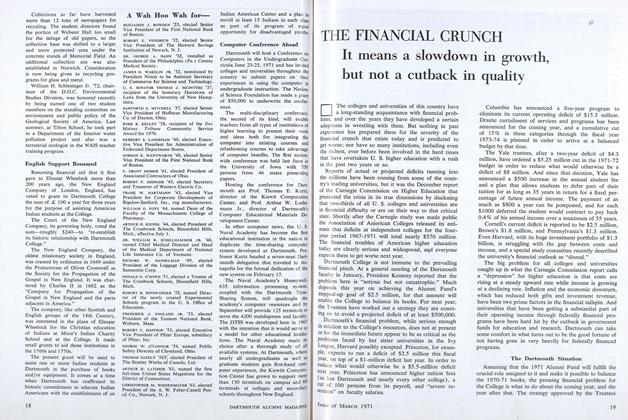

ArticleComputer Conference Ahead

MARCH 1971 -

Article

ArticleFINE ARTS BUILDING GIVEN

FEBRUARY, 1928 By F. P. CARPENTER -

Article

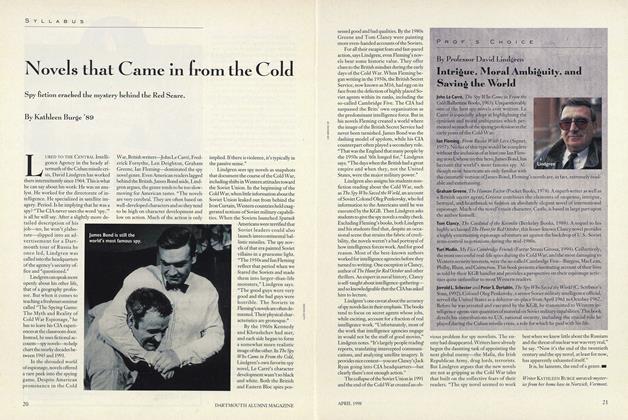

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

APRIL 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89