to lie between moving heaven and earth to provide an endowment fund, sufficient in its principal sum to yield a large annual interest, and taking up a collection every year which shall represent that interest. Something like this is involved in the "Alumni Fund" at Dartmouth, appeals for which are now in season. What we do annually is to provide by contribution the money which would otherwise accrue from an invested endowment. This has certain drawbacks, chiefly the recurrent necessity of giving from year to year, which a contribution to a permanent endowment would avert. But the advantage lies in the fact that what one thus contributes in 10 years is probably less than one would have to raise in one year to provide an endowment large enough to be fully sufficient. In other words it comes to about the same thing in the end, dollar for dollar; but the giving of ten small annual contributions comes more easily to most of us than the making of one prodigious gift would do.

Notoriously the student who is educated at this, or at any other college pays much less than his education costs the college. Even with the tuition fixed, as it is- now at Dartmouth, at $250 a year the student is still the beneficiary of a deficit which the alumni body has in some way to make up; and the doing of a substantial justice by the teaching force probably insures the permanence of a deficit not very far from the usual proportions when tuition was lower. But it has been found possible to keep the ball rolling by annual contributions to the Alumni Fund, without the expensive organization and delays which an endowment campaign would involve, so that in all probability this expedient will endure for some time to come.

Other advantages suggest themselves. Our belief is that the necessity of making repeated small gifts, rather than one large one, bends to retain the direct interest of alumni which might otherwise dissipate if we made one job of it and got the endowment raised once and for all. One might, in that case, have the comfortable feeling that every needful step had been taken and that the subject could be dismissed altogether from mind; whereas now we have the steadily recurring need which keeps the college actively before vis as a part of our life — the one thing we believe should be most harped upon in such columns as these. For it isn't merely the money of her alumni that Dartmouth requires. She needs the interest and the active service of her sons. She needs to have them feel that they remain an integral part of her existence, just as surely as the men in college are.

It is improbable that the average contributor to the Alumni Fund will, in the course of years, do much more than repay with interest the discrepancy between his own tuition fee and the cost of educating him. That, however, need not concern us. We are facing the period of readjustment in which new conditions, which not only perpetuate but also intensify old discrepancies, will have to be met. In a great number of colleges this has been done by the "drive" process, designed to secure permanent sums of several million dollars. With the multiplicity of such demands and with the waning of the enthusiasm to give which was born of the war, the possibilities have been minimized. It is very doubtful that Dartmouth could with the needful degree of success instigate such a movement now. Failing that, it is necessary to tide over until a more convenient season, and that is what is being done, year after year, by the Alumni Fund raised in lieu of regular income from an invested principal of millions.

It should be needless, and we think it is, to urge Dartmouth men with any special vehemence to undertake the manifest duty which the annual provision of this fund entails. It will be easiest of all if men train themselves to regard it as a perfectly regular visitant, make due provision for meeting it, and cease to look upon the Alumni Fund as a transitory or unusual thing which belongs to this 'one year rather than to others. After all, what most of us surrender to the upkeep of this fund is not going to beggar us — and it is possible to off-set it against income taxes!

We note with approbation also a growing class rivalry, which is sure to assist in the raising of a proper fund. No class wants to be rated low in proportion of contributors — but some of us have awakened to the sad fact that this was happening to our own classes and have taken a pride in altering the figures. Now and again a bit of class effort has prodded the slow of heart into giving twice or thrice what had been secretly determined upon as the extreme contribution, it being made clear that to do less would be unworthy. Class efforts are of the utmost value in such a case, because a man left to himself is prone to whittle down his estimate of his own proper portion until it is absurdly less than his due. No exigent class secretary ever got more out of his class than it could really afford; but many an undirected or unexhorted class has given infinitely less than it ought to do. Worst of all, too many classes rest content with the participation of a ridiculously low percentage of their living membership in this common duty of all.

Our experience has been that any class, once it is alive to the facts and perceives itself to be among the tail-enders in the league, so to say, will cheerfully pull itself together and change all that. Of course the more nearly universal is this support for the Alumni Fund, the lighter the burden on the individual alumnus.

Speculation as to the reasons why Dartmouth college has lately grown so amazingly are interesting but baffling — and are, after all, of much less direct importance than sober reflection upon two concrete problems now before us; to wit, how to care for this inundation of students, and how to deserve a continuance of the currently obvious popularity.

The point mentioned first is no doubt the more pressing matter. The college, according to Dean Laycock, seems practically sure of a larger number of applicants for several years to come than it can accept. Certainly it has so many in sight for. the next two years as to warrant preparation for the persistence of the demand upon our facilities. At the end of January, when the door was closed upon the present flood of applications, there were on file in the offices, at Hanover, 1200 names of young men desirous of entering the next freshman class; and the number already on file for the year following was so much greater than the previous record at that date as to make it desirable to frame certain rules dealing with the case.

These rules include provisions safeguarding the preference of the sons of Dartmouth alumni who are properly prepared, and also the sufficient recognition of the claims of residents of the state of New Hampshire. These stipulations are manifestly essential. A further wise precaution is the reservation of SO places to be held by the president and the dean for exceptional instances, to be acted upon in the light of their own judgment. In such a matter much depends upon the good sense and fairness of those charged with the discrimination — and of these there is in present circumstances no possible question.

There remains the solid fact that of 1200 applicants for the next freshman class it is physically impossible to receive more than 700 at the outside — probably not more than 600. In other words, the college has before it a problem which in cities would be called a "housing proposition." The college is as full as it can be, between the incoming freshmen and the flood of those who wish transfers from other colleges to our upper classes. Dean Laycock told the Boston alumni recently at their dinner that had all the applicants for transfers been received it would have precluded the reception of any freshman class at all. The safe course for the aspiring youth who would be numbered among our fellowship, then, is to start right by registering early as a Dartmouth man ab initio.

Since a freshman class of rising 600 appears to be regarded as one which the present college can handle, the question presents itself whether or not it is wise to expand with the expectation of receiving still larger classes in the future. In other words, if present housing conditions suffice for the' acceptance of a limited number, should that number be further augmented by the provision of yet more dormitories? Or is the college as large now as it is profitable for it to be ?

One recognizes that as such recordbreaking classes proceed through their course a certain erosion is inevitable, productive of smaller numbers at graduation than at entrance; yet it is certain that the huge freshman class of today will maintain a reasonable proportion of its hugeness throughout; and that this, by pressing backward, must restrict the room available for subsequent entering classes. Without any increase at all in later classes the demand for dormitory facilities is thus sure to be a serious one, lest we face the necessity of confining the new-comers to numbers even lower than 600.

To what Dartmouth owes this increment in popularity seems doubtful, even in the minds of those best qualified to judge—to wit, the president and the dean. Reasons suggested by the latter at the Boston meeting seem to us imperfectly to account for the growth. President Hopkins last summer professed himself to be thoroughly mystified by it. The immediately important thing is the fact that it is with us and must be dealt with in such a way as to insure the continuance of upper classes far in excess of the previous numbers, without too greatly curtailing the number of future freshmen.

It all comes down in the end to a consideration of the total number of students of all classes, properly apportioned among the four years, and with due regard also for the growing popularity of graduate work. How big can Dartmouth be — and still be Dartmouth ?

We have referred to our desire that alumni express their beliefs and opinions freely by writing to the editors of this MAGAZINE—and we would now renew that wish with especial reference to the proper policy of the college as affected by its size. Just what is the saturation point, with special regard to the maintenance of our democratic tradition-the point beyond which we cannot safely go without forfeitures of our goodly heritage? We assume that such a point does exist, since it has long been the plea of smaller colleges when arguing their case as against the larger ones; but where does the little college leave off, and where does the big college begin? And at what point does the big college cast loose from its ancient faith, so that a chemical, as well as a purely physical, change" occurs in its nature? Is there not in this a suggestion for the expression of alumni opinion?

Deserving to hold the present degree of popularity with such as seek higher education appears to ,the editors to be a phase of the problem which is inseparably bound up with the one just mentioned. We shall deserve to retain our hold upon public esteem if we deal adequately and convincingly with those already enrolled. To give to such a really liberal education, as well as to surround them, with appropriate conveniences and comforts, is the task — and the efficacy of its accomplishment will be inexorably judged by the product itself as it is viewed by the world of men. When all is said and done, colleges stand or fall by the standing achieved by their alumni. To be possessed of handsome buildings and eminent teachers is not in itself enough. The real monument is the resultant man and his revealed capacities as the world sees them. We speak now of sustained, rather than sporadic, popularity.

Wherefore in addition to the projects for more and better physical facilities, what about the education offered? That, in the last analysis, is what the college exists for, although it is sometimes easy to forget the fact in the multiplicity of college complexes. Is Dartmouth in any danger of drifting from the status of the college to that of the university, by the expansion of her mental bill of fare ?

There may be need for a restatement of the definition of a "liberal education." It is certainly a very different thing from what it. was in the days of President Lord — or even in the day of President Bartlett. The scope of the so-called "liberal arts" ("liberal" because originally only such Romans as were freemen could pursue them) used to include the "seven branches of learning — grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy." The list has been recast to include the various sciences, history, philosophy and so forth—with, one suspects, more and more stress on the sciences, and less and less upon the once-prized humanities. But for general purposes one may say that a liberal education today means such education as best fits a man for the efficient conduct and enjoyment of life, with particular emphasis on the enjoyment. To fit men for the earning of their bread by special forms of activity is the function, not of the liberal,"but of the technical education; not of the college, but of the technical or professional school.

It is no rash assumption that the alumni would regret to find Dartmouth drifting from the estate of a college inculcating the liberal arts to that of a university adding thereto a heterogeneous mass of technical or professional schools. The college has to draw a nice distinction between giving the students too freely what they think they want and giving them too much of what th : educators think they ought to have. It has been found necessary to set metes and bounds to the elective system: and it will no doubt. be found essential to confine the Dartmouth curricula to the furtherance of liberal education, leaving the technical training to such as make that their main object in teaching.

But bigness in itself impairs educational efficiency; and a too serious impairment would, we believe, react ultimately against the standing of the institution as measured by its mass of alumni. In short, our growth is not an entirely unmixed blessing. It carries with it a potential source of trouble, merely because such large institutions have the defects of their qualities. The fundamental question, as before, is: "How big can Dartmouth be, and still be Dartmouth?"

Just as the educational world was preparing to say the committal prayers over the grave of the Greek classics comes the news from Wellesley that the number electing Greek among the young women students of that excellent college has in the past two years more than doubled. That is to say, where only 38 girls were taking Greek in 1918, there are this year 84 enrolled. A year ago the number had advanced to 68 and the gain persisted into the present college year. What another year will reveal no one can say — but it will be surprising if the gain long manifests itself in any similar ratio. The saturation point is too soon reached when it comes to classics in modern times.

Nevertheless the recrudescence of the study of Greek is welcome to many of us — old-timers, who were brought up to think of Greek as one of the essential connotations of a college experience. To see the study of our boyhood familiars — Xenophon, Homer, Thucydides, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Anacreon, Socrates, Aeschines and the like — contemned as a futile expenditure of time has been irritating. It hadn't occurred to us that our time was wasted — unless it were aS a passing fancy while one was still a student. There are weary moments, when one has wrestled with obscure text and lexicon in vain, in which one hastily consigns the whole Hellenic crew to an unmerited perdition. But after one has been some time out, no longer labors under the daily necessity of doing 300 lines of the Iliad, and finds himself appreciating erudite allusions in sermons and books, one begins to plume one's self on being a bit of a Greek.

We all like to feel that we understand and use English rather better for our drill under "Roots" and "Tute," and as a matter of fact we do. There is no longer very much Greek sticking to us — but it has served its turn. It barely introduced us to the realms of gold — but it left us with an idea of grammatical structure, root-meanings and other things, which are not amiss even for the purely scientific mind.

Just what has produced the increase at Wellesley remains a mystery, for it cannot be accounted for on the basis of the total growth of the student body. The most one may say is, it happened.

By the way, what has become of the project, once mooted in college circles, for causing the Greek classics to be read in translation by such as refused to study them in the original? The idea had much to commend it. After all, it is better to know a little something of these classic masterpieces at second hand than it would be to remain utterly ignorant of them — provided one seeks to pass current as a gentleman or lady of culture. Making due allowance for the contention that no translation ever does justice to an original — a very rash contention indeed — the fact remains that language is but the common denominator of thought and that what Aeschylus had in mind when he produced his "Agamemnon" may be set forth with perfect clarity in any other tongue, by one ,who comprehends the idea as it stood in Greek and has the requisite mastery over his own forms of speech.

One waxes a bit impatient with the repeated assertions that no translation ever adequately represents an original. There is no reason why it should not — and there is even a bare possibility that, in the hands of one entirely great, a translation might surpass the initial form in which it was given to the world — for the purposes, at least, of a mere modern reader. If one held a brief for Greek as a study appropriate to colleges it might better be on the ground of its assistance to a more flexible use of the mind, the tongue, or the pen, than upon any theory that it was the sole and only way of knowing the great classics. The latter can be known by other means, and if many are to know them it will have to be by other means, than the study of Greek. The number of Greek students who obtain actual acquaintance with more than a single tragedy among the titanic survivors of the great Athenian age is deplorably small. One labors over "Iphigenia in Aulis," spelling it out a few pages at a time — passes the final examination — and that's usually all. There are, however, something over thirty surviving tragedies from the pens of the immortal three — and it were surely a sin to overlook the trenchant comedies of Aristophanes.

Those familiar with the really great translators, past and present, know that to despise their versions of these masterpieces is folly. Only a pedant claims that the reader who knows "Alcestis" only through Browning, or "The Frogs" only through Gilbert Murray has never really been introduced to either. That curious omnium gatherum, Everyman's Library, has probably done more to popularize the modern reading of the great Attic tragedians than all the colleges together have done in a generation.

One not on the ground and not enrapport with educational affairs cannot know to what extent the idea has been adopted of making translated classics a course in those colleges where Greek is studied but rarely if at all. It seems to the present editors, however, that the idea is much too good to be let drop, or to be but meagrely availed of.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

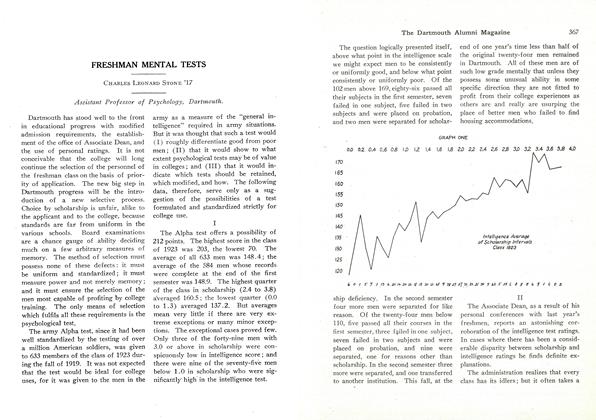

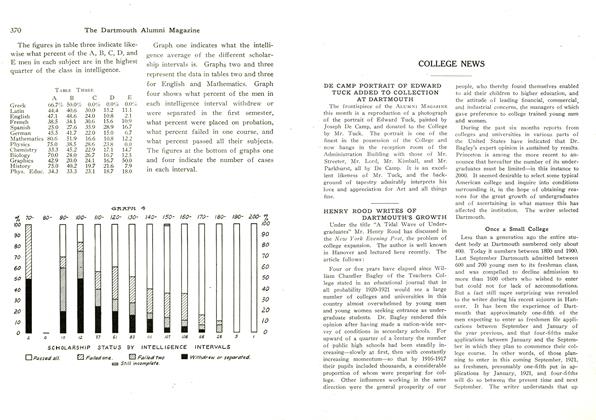

ArticleFRESHMAN MENTAL TESTS

April 1921 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleAMERICAN PROFESSORS AND STUDENTS RESENT CHARGES AGAINST FRENCH PEOPLE

April 1921 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1921 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Article

ArticleHENRY ROOD WRITES OF DARTMOUTH'S GROWTH

April 1921