PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 April 1921

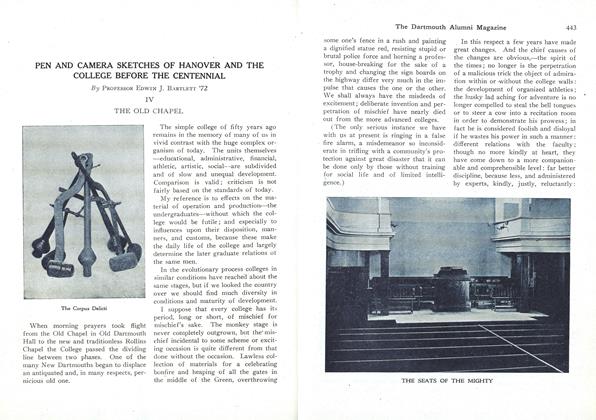

III

The Dartmouth Hotel

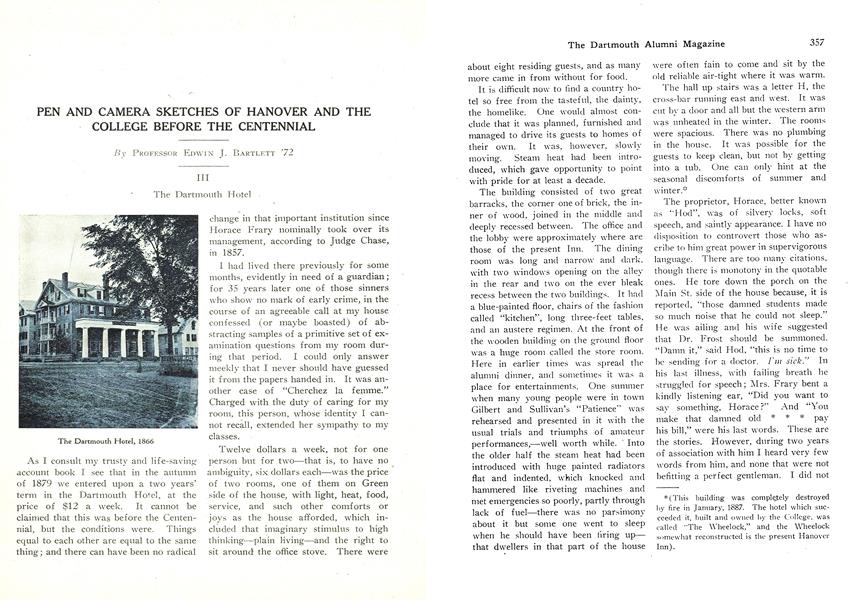

As I consult my trusty and life-saving account book I see that in the autumn of 1879 we entered upon a two years' term in the Dartmouth Hotel, at the price of $12 a week. It cannot be claimed that this was before the Centennial, but the conditions were. Things equal to each other are equal to the same thing; and there can have been no radical change in that important institution since Horace Frary nominally took over its management, according to Judge Chase, in 1857.

I had lived there previously for some months, evidently in need of a guardian; for 35 years later one of those sinners who show no mark of early crime, in the course of an agreeable call at my house confessed (or maybe boasted) of abstracting samples of a primitive set of examination questions from my room during that period. I could only answer meekly that I never should have guessed it from the papers handed in. It was another case of "Cherchez la femme." Charged with the duty of caring for my room, this person, whose identity I cannot recall, extended her sympathy to my classes.

Twelve dollars a week, not for one person but for two — that is, to have no ambiguity, six dollars each — was the price of two rooms, one of them on Green side of the house, with light, heat, food, service, and such other comforts or joys as the house afforded, which in- cluded that imaginary stimulus to high thinking — plain living — and the right to sit around the office stove. There were about eight residing guests, and as many more came in from without for food.

It is difficult now to find a country hotel so free from the tasteful, the dainty, the homelike. One would almost conclude that it was planned, furnished and managed to drive its, guests to homes of their own. It was, however, slowly moving. Steam heat had been introduced, which gave opportunity to point with pride for at least a decade.

The building consisted of two great barracks, the corner one of brick, the inner of wood, joined in the middle and deeply recessed between. The office and the lobby were approximately where are those of the present Inn. The dining room was long and narrow and dark, with two windows opening on the alley in the rear and two on the ever bleak recess between the two buildings. It had a blue-painted floor, chairs of the fashion called "kitchen", long three-feet tables, and an austere regimen. At the front of the wooden building on the ground floor was a huge room called the store room. Here in earlier times was spread the alumni dinner, and sometimes it was a place for entertainments. One summer when many young people were in town Gilbert and Sullivan's "Patience" was rehearsed and presented in it with the usual trials and triumphs of amateur performances, — well worth while. Into the older half the steam heat had been introduced with huge painted radiators flat and indented, which knocked and hammered like riveting machines and met emergencies so poorly, partly through lack of fuel — there was no parsimony about it but some one went to sleep when he should have been firing upthat dwellers in that part of the house were often fain to come and sit by the old reliable air-tight where it was warm.

The hall up stairs was a letter H, the cross-bar running east and west. It was cut by a door and all but the western arm was unheated in the winter. The rooms were spacious. There was no plumbing in the house. It was possible for the guests to keep clean, but not by getting into a tub. One can only hint at the seasonal discomforts of summer and winter.*

The proprietor, Horace, better known as "Hod", was of silvery locks, soft speech, and saintly appearance. I have no disposition to controvert those who ascribe to him great power in supervigorous language. There are too many citations, though there is monotony in the quotable ones. He tore down the porch on the Main St. side of the house because, it is reported, "those damned students made so much noise that he could not sleep.' He was ailing and his wife suggested that Dr. Frost should be summoned. "Damn it," said Hod, "this is no time to be sending for a doctor. Itn sick. In his last illness, with failing breath he struggled for speech; Mrs. Frary bent a kindly listening ear, "Did you want to say something, Horace?" And "You make that damned old * * * pay his bill," were his last words. These are the stories. However, during two years of association with him I heard very few words from him, and none that were not befitting a perfect gentleman. I did not hear what he said when his peculiar and uncertain temper had been aroused, or when he stood coatless and hatless in the coldest weather, at the tail of the meat cart bargaining for joints to feed people who never stayed fed longer than over night.

Mr. Frary took the Boston Journal as others took alcohol or stimulating drugs. As he read it he growled and muttered, grew violently excited, and finally flung the paper as far as he could across the room. No persuasion could induce him to change to a less irritating source of news. His behavior was far worse than that of the young miss of Back Bay,

"Whose conduct was very blase; While yet in her teens She refused pork and beans, And once threw a Transcript away."

Yes he carved, very skilfully, in his shirt sleeves, and with his back towards the pensioners. Knowing the legend, we watched furtively and anxiously to discover whether he did wipe either his nose or his knife on his vest. The verdict was "not proven, but put on another vest."

There was a clerk whose name was not Rufus, hard worked and reluctant. Perhaps the greatest sorrow of his life was having to sell six five-cent see-gars for a quarter. Next to that was the grievance of letting anyone into the house after 10 p. m.

But whatever Hod or the clerk whose name was not Rufus may have done or have been in the stable, the lobby, or the street, the autocrat of the breakfast table and all the tables was Mrs. Frary, whose given but unused name was Sarah; and she maintained her authority by constant presence, eagle vision, disconcertingly acute hearing, a far-carrying voice that never missed, and a firm conviction that she was responsible not only for our nutrition but also for our manners and morals.

Very tall and very spare and very straight and very angular, with a neat brown-haired head-covering about which there was no deception (unless there were two) curving from a broad parting low to the ears, and with slippers always down at the heel, she shuffled rythmically from one end of the room to the other bearing food, supervising, warning, commanding, seldom comforting. Her thin face with its down-curving lines was always serious. If you ventured to jest, an appreciative gleam would come into her eyes, and if she was in very amiable mood she would let it go; on less favorable days she would repeat and dissect it in a loud clear flat voice to the intense but suppressed delight of every one in the dining-room, except the joker.

George Eliot declares that a difference of taste in jokes is a great strain on the affections. The autocrat had her own taste. Did you especially object to the flavor of sage you might hear her compelling voice, "Give him plenty of the turkey stuffing, Angelina." She nearly reduced a mother to tears by commenting loudly on the inebriated condition in which the mother's son came in the night before, and she continued the subject at intervals for a week though every one knew that while late the young man was not drunk. Early one July morning a small new boarder came into the house. This Mrs. Frary announced to the breakfasting boarders by the remark in her long range voice to relatives of the debutante, "It was rather Frosty early this morning, wasn't it?" A stranger demanded a bath and his case was referred to Mrs. Frary and disposed of thus, "You want a bath? Didn't you see the river when you came up from the depot?"

And you were expected to eat what she allotted to you. You asked for bread and she was likely to shuffle over to you and inquire, always in the far-carrying voice, "What ails the biscuit this morning? I made them myself." Angelina said "Pork chop, sausage, and meat and tater hash," and you expressed a preference for sausage, to hear, "Guess you better have meat and tater hash; sausage might not suit you." Or you heard, "Hot coffee? If he wants his coffee hot he better come earlier to his breakfast." A veteran boarder requested underdone meat one day, and we heard from the region of the serving table, "You take him back this; raw meat aint good for him." A reckless traveling man actually took exception to the food that was brought him and sent it back. Our, first notice of it was, "Hey! what ails it?" Then taking the plate in her own hands she marched with flapping heels upon the daring man. We grasped the sides of our chairs and listened. "Say, what's the matter of this? Aint it good enough for you ?" He looked up, then muttered something inaudible even in the supernatural stillness of the room. "Well, it's the best we got; I suppose you needn't eat it if you don't want it." But he took it. Whenever she thus crushed an upstart an appreciative twinkle lingered in her glances for a minute or two.

Who of the time will forget the sentence of expulsion solemnly pronounced and executed on Squire Duncan, brother-in-law of Rufus Choate, and McClary of the bookstore, for habitual and incorrigible tardiness at breakfast. But they were almost as much fixtures of the house as Mrs. Frary herself, and after missing them for a week she changed her mind and called them back.

When the few festal days of the College arrived Mrs. Frary came into her own. The great ones of the earth, the trustees and judges and governors, placed their feet under her mahogany, and in some instances made rapid plays with their knives, but there was no servility in Mrs. Frary's manner, although we common feeders were made to see distinctly that the real thing had come and that the tavern was now serving its highest ends. "I'm getting along about as usual, judge; I hope your rheumatism is better." "Will you have meat pie or rice pudding, doctor?" "We have some nice haddock fish today, governor; shall I bring you some ?" all conveyed a fine sense of social equality weighted with appreciation of their temporary alimentary dependence. (We never were quite clear why it was always "haddockfish" that was offered, but the most probable theory is that the discrimination thus suggested was a delicate courtesy to Professor Haddock's aged widow who was a distinguished and stately boarder. Her egg, by the way, was a well-known feature of the breakfast, because, being deaf, she did not know that the tinkling as she stirred it in the glass was loud enough to obscure the chapel bell. She was a good sport, and when in the panicky time of the fire Mr. Henry Rood hastened to her rescue with the word that unless she hurried it was uncertain whether she could get out she replied, "Harry Rood, I've never hurried in my life, and I m not going to begin now, and fully dressed and composed she took his arm and marched through the smoke into safety).

But the gentler elements were mixed in Mrs. Frary, and if one could penetrate to the great clean kitchen and find her, a prudent Penelope, sitting with the weary flat feet in an otherwise vacant oven, while she regulated the maids with eye and voice, it might be that any request even to cake or oysters in the evening would be granted. If, as sometimes happened, a genuine liking for some boarding lady took hold of her, that one might even come into the kitchen and make things, or have toast at supper. She was a constant friend to the poor; and impecunious boarders touched her sympathy, especially if the bill was old and large. That baby born on the Frosty summer morning fetched her, and for the only known time in two years she climbed the stairs all the way from the first to the second floor to pay a visit and to see her have her bath.

The food materials were generally good. The chef was about average Yankee, neither best nor worst. Options in food were not much encouraged. There were certain memorable fixtures, — fish on Friday, baked beans and brown bread Saturday night, fish cakes Sunday morning, oyster soup and chicken or turkey Sunday noon, all of course. And there were some immutable grievances. Some people love sage and some hate it; but it was a constant and abundant constituent of that part of fowls which is so generously given out in hotels and boarding houses, — the stuffing. There is an humane invention of the clever chemist known as baking-powder, in which the gas-giving compounds are shrewdly mixed to baffle culinary recklessness. Before its day, when the neat-handed Phyllis or the sturdy Mary Ann came in from the afternoon out and rushed to stir up "soda biscuit" for supper, she made sure of at least twice the necessary sal aeratus, with grievous offense to sight and taste in the product. Yeast was strictly domestic in those days. Like the fire of the Vestal Virgins the home-made supply was never allowed to get out. Or perhaps a lump of dough was carried over from one rising to the next. Thus besides the proper alcoholic ferment much "wild yeast" was propagated to make acetic acid and lactic acid and other acids, and the bread was almost always sour. So no gift more precious could be borne to anyone condemned to th 6 hotel dietary than a loaf of genuine home-made bread. It was an occasion for gloating. Many such gifts were made and remembered to the present day.

I am permitted to record some of the experiences and recollections of N. A. McClary '84, who boarded at the Frary table for eight years and roomed in the house for two.

"I have heard Mr. Duncan say that in his younger days Mr. Frary was a very interesting, and attractive man. He had been a shoemaker before he became a hotel keeper. He was remarkably wellread and knew Shakespeare as few men know him. Mr. Frary often had a volume of Shakespeare open before him as he worked at his bench and could repeat from memory long passages. Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, when he was a professor in the Medical School, knew Mr. Frary well and greatly enjoyed his society. Mr. Duncan said that he frequently found Dr. Holmes sitting in Mr. Frary's shop, the two discussing Shakespeare while Mr. Frary pegged away at his work.

"I remember one day when Mr. Frary was at the desk, as infrequently happened, a young mincing sort of man, whom I guessed to be a New Yorker, floated into the office with, 'Can I have my shoes shined ?' Mr. Frary leered at him but did not answer. He repeated his question rather insistently when Mr. Frary indicating the little corner enclosure where the washstand was located said, 'There's the blacking; shine them yourself.' The New Yorker inspected the hard worn-out brush and the empty blacking box and coming out with the brush in hand ventured the inquiry, 'Where can I find some blacking?' Then the bolt fell. 'You damned fool! There's blacking enough on that brush now to shine a hundred pairs of shoes.' I think that the incident was rather characteristic of his attitude towards guests."

(Yes, and of the employes. After any little congestion of business there was a tendency to speed the parting guests very quickly and then give thanks. It might almost be said they were ready with the swift kick).

"My personal relations with Mr. Frary were rather friendly. 'I kept out of his way pretty well. But one night Billy Reding's dog followed me in and upstairs. Mr. Frary happened to be passing through the hall and saw us. He immediately let loose a torrent of profanity and abuse and ended by ordering me out of the house. I was not able to get in a single word. But as soon as he had disappeared Mrs. Frary came out of her room and asked me not to go and not to mind it. She then made the only derogatory remark that I ever heard from her concerning him, 'lf you knew what I have to stand from him you would think this nothing.' He had grown very sour and irritable towards the latter part of his life. The students sensing this made life miserable for him, often shouting in a chorus as they passed his windows 'O, Hod!' and other inane calls. I was told that he had the veranda, originally built on the Main St. front, removed because the boys had the habit of stopping there as they passed and dancing clogs for his benefit.

"I have been told that Mr. Duncan once defended Mr. Frary in a lawsuit and that the latter in the fullness of his gratitude had impetuously told him that he would board him for the rest of his life. Be that as it may Mr. Duncan held on for a long time and Mr. Frary got tired of the arrangement although it was clear that he admired his star boarder. During his last illness he was delirious a part of the time. One day Mr. Duncan went in to see him. Mrs. Frary bent over the bed and said, 'Horace, this is Mr. Duncan come to see you; you know your friend, Mr. Duncan.' 'Know him? Damn him; I should say that I do know him! He hasn't paid a cent of board for 20 years."

(It will be noticed that this is another form of the legend already cited).

"Mrs. Frary was a very superior woman. I did not realize it so fully at the time as I have since. I have known very few women of so much character, so forceful, so intelligent and so good at heart. How she dominated the diningroom! It was clear even at Commencement time that she acknowledged no superiors and very few equals. She liked to talk with the men and seemed to have little use for the 'weaker sex.' And the men liked to talk with her, even the most distinguished of them. Mr. Stoughton, the New York lawyer, was one of her favorites. He had a home at Windsor and sometimes drove to Hanover for dinner. She would limp over to his chair, shake hands with him and personally take his order. Before he left the room she would draw up a chair, sit down beside him, and they would have the best of times. It would be the same way with Dr. Peasley and many others. She liked to talk to Mr. Duncan, but for the most part ignored Mrs. Haddock, widow of Professor Haddock who was once Minister to Portugal, who sat next to him.

"It was a real, treat to hear Mr. Duncan talk. Mrs. Haddock was an excellent foil for him. Mr. Duncan would tell stories of his brother-in-law, Rufus Choate, and Mrs. Haddock liked to tell of her experiences at European courts. She had been presented at several, either going to or returning from their mission. In England she had danced in a quadrille with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. At Lisbon she had given English lessons to the young Prince. She had entertained Daniel Webster and many other notables in her own home. She had much to say about her brother Richard B. Kimball. She loved to tell about the courtship of her niece by Levi P. Morton, and how when he first came to Hanover in charge of a branch men's furnishing goods store the faculty people would have nothing to do with him socially. 'And see where he is now !', — at that time millionaire banker and Minister to France."

(Mrs. Haddock's conversation was often of the nature of a monologue and frequently superposed irrelevantly upon other talk. If one wished real conversation with her it was necessary to sit close and hurl winged words into a large ear trumpet.)

"Mr. Duncan was emphatically the autocrat of our table. He would raise his voice slightly, as Mrs. Haddock was quite deaf, so I got much of the conversation even before by gradual promotion, seat by seat, I reached an eminent position at Mr. Duncan's left hand and opposite Mrs. Haddock. He was the best conversationalist I ever listened to. All his long life" (Mr. Duncan died in 1883 in his 76th year.) "He had been a careful student of books and of men, to the neglect perhaps of his profession. His enunciation was slow and musical, his language prefect, some might think it almost stilted, never a suggestion of slang, no 'young words' as Professor Parker used to call them, and the matter was always interesting. I have always felt that those table talks with Mr. Duncan, running as they did through several years were a very important part of my education."

Asa W. Waters of the class of 1871 permits me to offer his evidence that in 1870 Squire Duncan was not lacking in professional adroitness. This is not inconsistent with the traditions of his later years.

"Mr. Frary raved loudly and continuously, and said "cuss words" over the state liquor ' prohibitory legislation, or threatened legislation, which he believed was an encroachment on personal liberty, and unconstitutional, and he sought frequent legal advice from Squire Duncan. Mr. Frary had a small room for an office at the front entrance to the dining-room, and when the wide door to the latter .was open we could hear conversations in this little room whose door was always open and Mr. Frary never lowered his voice, and I give a conversation that I thus overheard, and which has for some reason lodged in my memory ever since.

(Mr. Frary) "Squire Duncan, this being the beginning of a new year (1870) I have made out your bill for board for the past year; may I hand it to you?"

(Squire Duncan) "Certainly, Mr. Frary; how much is it?"

"Fifty-two weeks at four dollars per week I calculate is $208; am I right ?"

"Perfectly, Mr. Frary. Will you let me take the bill, over to my office, for, I think I have some charges against you, Mr. Frary, for legal advice."

"All right, Squire Duncan."

Our curiosity was satisfied, for we overheard the final settlement. "I find, Mr. Frary, that I have charges against you on my books, totaling $260.25.

"Why, Squire Duncan, I did not think I owed you so much as that. What is the twenty-five cents for?"

"Do you not remember that I acknowledged a deed for you? I cannot help, Mr. Frary, but think from your manner that you feel that I have charged more than you expected, but there was much legal effort and research necessary to give sound legal opinions upon the constitutional questions you submitted to me; but I do not wish you to think you are overcharged, and if you will receipt in full payment your bill against me. I will do the same with mine against you."

"All right, Squire Duncan."

*(This building was completely destroyed by fire in January, 1887. The hotel which succeeded it, built and owned by the College, was called "The Wheelock," and the Wheelock somewhat reconstructed is the present Hanover Inn).

The Dartmouth Hotel, 1866

The Dartmouth Hotel, from N. W. Corner of the Green, later

A Nearer View

AS IT APPEARED BEFORE THE FIRE, IN 1887

THE LAST OF THE DARTMOUTH HOTEL

A FAIR PARTY From The Wheelock which was altered and called the Hanover Inn in 1902

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIn these days of "drives" the choice seems

April 1921 -

Article

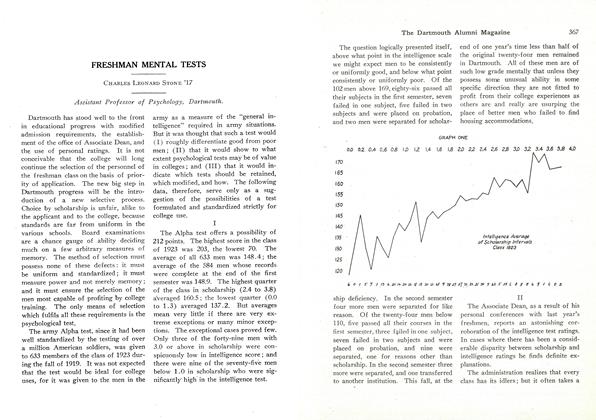

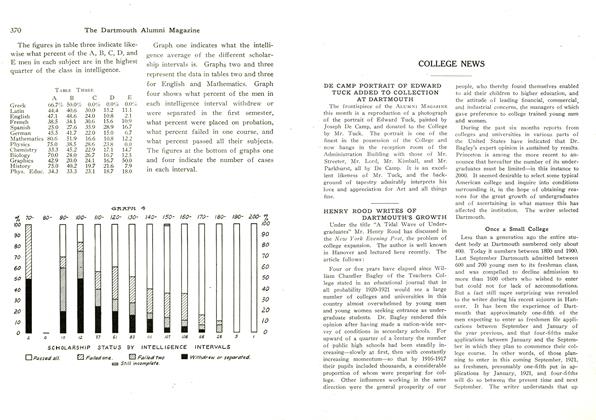

ArticleFRESHMAN MENTAL TESTS

April 1921 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleAMERICAN PROFESSORS AND STUDENTS RESENT CHARGES AGAINST FRENCH PEOPLE

April 1921 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1921 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Article

ArticleHENRY ROOD WRITES OF DARTMOUTH'S GROWTH

April 1921

EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72

-

Article

ArticleATHLETIC SPORTS AT DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1905 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

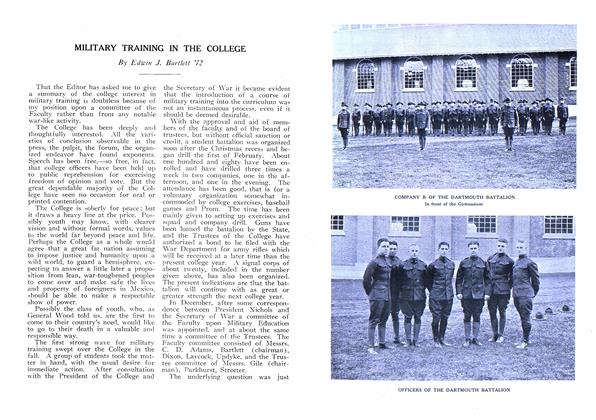

ArticleMILITARY TRAINING IN THE COLLEGE

June 1916 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

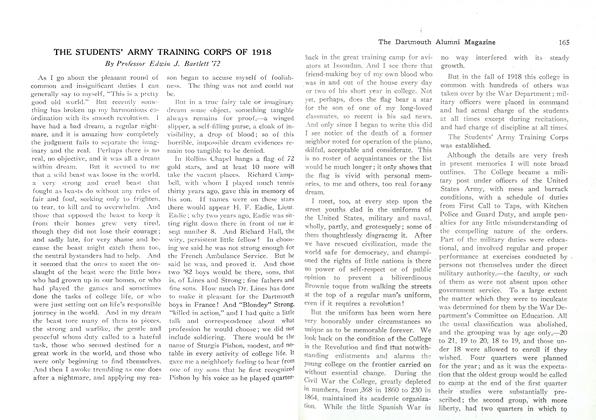

ArticleTHE STUDENTS' ARMY TRAINING CORPS OF 1918

February 1919 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

May 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE REJOINDER OF JOAN

August, 1923 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleMATERIES MEDICI

June 1924 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72

Article

-

Article

Article"THE BEMA" ELECTIONS

June 1921 -

Article

ArticleINTERCOLLEGIATE CONFERENCE TAKES STAND AGAINST LIQUOR

June, 1923 -

Article

ArticleSnapped in Informal Classroom Scenes

April 1936 -

Article

ArticleFootball

December 1957 -

Article

ArticleRugby

December 1955 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

October 1940 By The Editor