who had been dropped because of unsatisfactory scholarship would be readmitted to the college will be generally approved. The reasons offered in support of this new and drastic rule should be convincing. The men who in past years have been given a second chance do not commonly graduate. Only one in four is said to have done so. The other three, and probably the fourth as well, have proved a drag on the rest. It is therefore decided not to continue the practice—which we believe to be practically universal among colleges—of affording a second chance. If a man wishes to graduate from Dartmouth, let him maintain his standing. Why not? It is possible, of course, that an occasional injustice will be done to an individual here and there by unswerving application of this rule; but it is absolutely certain that the old custom has worked wholesale injustice on the rank and file whose standing was consistently satisfactory, and the preponderance of the evidence thus favors the adoption of the new rule.

Out of 219 recent cases of men readmitted for study after failing to keep pace with their mates, it is stated that 70 had to be dismissed a second time for poor scholarship and that 50 others left voluntarily for the same reason. Forty-two managed to graduate—but not with creditable standing from the purely scholastic point of view. In fact every one of the 42 held his position in the class by reason of credits for war service without which each would have shared the fate of the others. In short, it is clear that the practice works badly—and, what is worse, is not sufficiently appreciated by its beneficiaries who so consistently omit to bring forth the fruits meet for repentance. There are said to be 57 students now enrolled at Hanover who have been readmitted after a previous failure and that of these only five have at present a creditable standing—14 having only "fair" records and 38 distinctly poor ones to show.

It must be admitted, then, that the chances of injustice are so small as to be negligible. Apart from failures due to illness, rather than to habitual indifference to college requirements, it is hard to imagine a probable case of unfairness in applying the new regulation.

This may prompt a moment's reflection upon the common classification of colleges—those that are "hard to get into but easy to stay in," and those where admission is easy but where continuance as a student is difficult. There may be colleges which do not fall into either one of these categories; i. e., there may be some which are both easy to get into and easy to stay in, and vice versa. But the average critic, acting perhaps on insufficient premises, usually catalogues the higher institutions in the manner first mentioned.

There is room for debate whether or not Dartmouth, even today, is too easy to enter, from the standpoint of the scholastic requirement;—but in view of the latest rulings it will nowhere be maintained that continued membership in the student body is unduly easy. This does not imply, either, that sustained membership is unduly hard. It is quite probable that no man of tolerable capacities need ever fail if he does even tolerable work.

Alumni drifting by easy stages into the sere and yellow leaf, and professors who are themselves no longer young but increasingly impatient of footless plodding, are not always capable of taking the students' point of view, or of recalling their own point, of view when they also were students. One makes due allowance for this and also for the fact that undergraduates themselves would probably in majority admit that a persistent shirker, who either cannot or will not maintain a passing mark, is entitled to scant consideration. In other words there is probably a common ground where crabbed age and youth may agree fairly well as to what it is and what it isn't reasonable to ask of average young men studying in modern colleges. If the college refrains from demanding the impossible, the least the student body can do is deliver the possible.

No one asks that all members of a class attain valedictory rank, or even qualify for the Phi Beta Kappa. The credit of the college demands that at least the passing mark be kept reasonably high—and by that one means high enough to make a college degree imply some thoroughly appreciable attainment, rather than become a meaningless parchment bestowed alike on the wise and the foolish. There is no occasion to suspect that American colleges are demanding excessive cultural exploits as the conditions precedent to the grant of an A. 8., or other cognate academic honor. There are times when one is tempted like Mr. Edison, to question whether the demand is exigent enough. But at least there can be small dissent, if any, from the requirement that students shall either live up to the standards which do reasonably obtain or shall drop out and make room for men who both can and will make the effort.

Current pressures on the physical capacity of Dartmouth college no doubt have operated to expedite the adoption of this rule. That, however, is a side-issue and does not go to the essence of the case. The main justification of. this refusal to accord second chances to men who fail to sustain the scholarship tests is found in the fact that it doesn't pay either the college or the men themselves to give it to them—on the face of the record.

The thing for a student to see to with the utmost solicitude should hereafter be his own security in collegiate membership. There are times when men less gifted than others persuade themselves that this task is made excessively hard for them—but it very seldom happens that this is really true. In the nature of things the standard certainly cannot be lowered to accommodate every grade of backward youthful intellect. However pleasant that would be, it wouldn't be fair to the college. Those who cannot keep up to the mark set as fairly attainable by any average student will failsometimes without their fault, but oftener because of persistent indifference and indolence. Such will simply have to go —and once gone, may not return. The more reason, then, to insure against the slips due to indolence or inadvertence, since such are to be irretrievable. It's easy enough to avoid them and the average man will avoid them hereafter with quite as much success as in the past. Perhaps with more.

There has been manifested of late in certain quarters a disposition to question the apparently well established truth that college education must necessarily be purveyed at a deficit—that is, that the tuition fees paid by any student in such an institution are certain always to fall far below the actual cost of what is offered him. Whether this familiar situation is or is not a needless one remains in doubt; but it is significant. that the question of its imperative necessity has been raised.

The questioning probably arises from the fact that almost every considerable college for men and women has in recent months been engaged in a campaign for the enlistment of endowment funds to make good the discrepancy between what the student pays and the cost of what he gets. It was morally certain that the multiplicity of these demands would prompt the query whether the situation was economically sound—whether, in short, it was businesslike. If the student pays far less than the cost of his education, why does this condition persist ? Is the raising of large endowment funds any guarantee that the discrepancy, even after pouring in the yield of the endowment, will not continue and make further demands imperative? Any other business' conducted in this way would fail. Private schools, conducted for profit, manage to pay. What makes the difference when it becomes the case of a college or university?

It may be granted, we believe, that the situation is at least one in which a question is justified, although one may not be too sure that it admits of a simple answer one way or the other. Broadly speaking, it may also be admitted that from the standpoint of ordinary economics the custom of taking only a partial payment from the undergraduate is unsound. The obstacles in the way of changing this situation, however, are very serious indeed and relate to something beyond mere businesslike efficiency.

At the outset it may be noted that tuition fees, although notoriously insufficient to cover what they are supposed to cover, are very high by comparison with what they formerly were. Expenses have advanced coincidently and the ordinary college term-dues still fall short by something like the usual margin of paying for the process in each individual case. Can term dues ever be figured in such a way as to meet, or nearly meet, the cost without debarring from college education all but the richer students ? If so, would the gain be worth the having, in terms of mere dollars and cents?

It is possible—and this suggestion has been seriously made—that something could be done at the other end of the problem by curtailing the cost of education, as well as by increasing the sum which the student pays. The suggestion includes a project for simplifying the curriculum by lopping off the "sparsely populated" courses, which often demand expensive equipment without attracting a sufficient patronage to justify their upkeep. There is in this something rather suggestive of a sordid, but on the whole pertinent, analogy between the college's intellectual bill of fare and that offered in wholly unintellectual ways by the ordinary social clubs and restaurants. Restaurants of the commercial variety, conducted for profit, have to pay; whereas pretty nearly every club restaurant runs behind and has to be made good by appropriations from other revenues. The reason is partly that the ordinary social club insists upon the provision of a well stocked larder for the occasional or sporadic demand—and does this deliberately, knowing that it "doesn't pay" in the financial sense; but regarding it as justified by other features.

It is doubtful that the college of our present day could afford not to sell education at less than cost. It would be possible so to impair the extent and variety of its offerings as to decrease its repute far beyond what would be gained in the way of making both ends meet, financially. Apart from the closing of little-frequented courses in the manner above suggested, there seems little that can be done. It is clear that even with the increases lately common in the salaries of the teaching force, the professors are very far from being overpaid.

In a word, it may well be that the proper estate of the American college inexorably demands the continued existence of this seeming defect—the failure of ordinary revenue to meet the regular running expenses.

The dedication a short time ago of the new chemical laboratory, the gift of the late Sanford H. Steele, provides the college with; a thoroughly up-to-date chemical headquarters for the study of this superlatively important science. The fact that Judge Steele was for many years president of the General Chemical Company naturally adds to the appropriateness of his gift. It was a thing of which the college stood in the utmost need, the old quarters having been sadly outgrown, partly because of the swiftly increasing size of the student body and partly because of the relatively greater interest which modern education is taking in the material sciences. The size and scope of the new laboratory appear to be such as adequately to provide for any probable growth that is now foreseeable.

It is not amiss in this connection to remark on the good fortune which Dartmouth has had in the form of wise gifts from generous gentlemen who have served on her board of trustees. Instances that suggest themselves currentecalamo are Mr. Parkhurst's gift of the administration building, Mr. Moore's endowment of the Guernsey Centre Moore Alumni lectureships, Mr. Streeter's gift of a magnificent organ to Rollins chapel, Mr. Hilton's several benefactions for the development of Hilton Field, Mr. Kimball's bequest to the college—and the magnificent chemical laboratory above mentioned, which Mr. Steele's munificence made possible.

Good news for all will be found in the report, hopefully indicative of many years' continued activity, that professor Edwin Julius Bartlett, whom we all know and love, is recovering his strength after a prolonged illness which was at fust legarded as alarming. Readers of this magazine will recall the delightful reminiscences of his student days which Dr. Bartlett published in these columns during last year—articles which it is hoped may be extended and continued, and which most certainly should be embodied in the more coherent form of a book. In these has been revealed the genial spirit of the man who for so many years bore so intimate a personal relation to thousands of Dartmouth students as the chief professor of chemistry. To the magisterial history of the college by Messrs. Chase and John King- Lord it is fitting to add this anecdotal commentary which throws so clear a light, not alone upon the life of the college, but also on the life of the town and some of its resident "characters," its traditions and its institutions. The best criterion for judging these writings of Professor BartLett may well be the fact that to more modern graduates, who had no personal recollection of "Hod" Frary and his famous hostelry, or of the hardships which Hanover offered to the student of the 70 s and 'Bo's, the pages were no less delightful than to the writer's contemporaries in college.

Dartmouth has arrived at the dignity of an additional dean. Mr. E. Gordon Bill, who relieves Dean Laycock of the care of the incoming students, represents in a way the natural development of that once familiar institution, the "class officer." The difficulty of making! the needful readjustments to a new and unfamiliar environment, which the estate of the freshman always involves, make this new college officer a highly important functionary and tend to equalize the tasks of dealing with but a single class and handling the other three, which have been in college longer arid may be supposed in consequence to be acclimatized. The freshman dean has before him the exacting task of bending the twig in the direction in which it is desirable it should grow to maturity in the college orchard—and one's recollections afford ample warrant for the belief that such a post will be no sinecure. The office of a dean never is. In fact there is need for some panegyrist to arise to extol in appropriate terms the efforts of college deans everywhere—the men on whose little noted efforts the morale of every college depends. One recalls from one's classical training the fact that the "Decanus" was originally "a chief of ten"—which may show how far we have come on the road, since Dean Bill will have under his charge something between 600 and 700 young men this year, and Dean Laycock more still.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleALUMNI COUNCIL MEETS

December 1921 By EUGENE F. CLARK -

Article

ArticleTHE BURYING GROUND

December 1921 By EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 -

Article

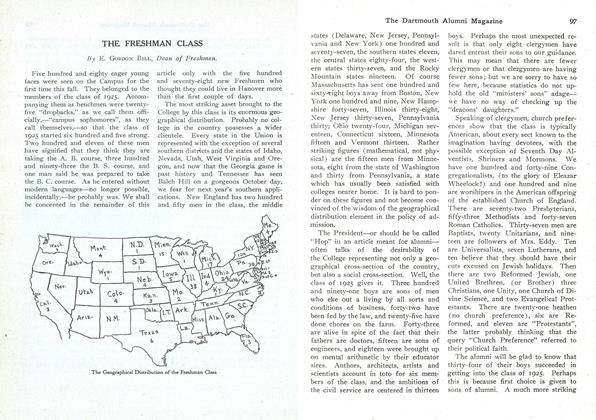

ArticleTHE FRESHMAN CLASS

December 1921 By E. GOKDON BILL -

Article

ArticleNEW FACULTY REGULATIONS

December 1921 -

Sports

SportsFOOTBALL

December 1921 -

Article

ArticleEXTRACT FROM MINUTES OF TRUSTEES' MEETING

December 1921

Article

-

Article

ArticleADDRESSES UNKNOWN APRIL 6, 1916

May 1916 -

Article

ArticleCivilian Positions

February 1943 -

Article

ArticleCommunity Development Conference.

APRIL 1966 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

SEPTEMBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleHazing, shooting lead to disciplinary action for fraternities

September 1986 -

Article

ArticleERRATUM

February 1941 By Leon B. Ricahardson '00.