of loss in the departure from its staff of Homer Eaton Keyes, whose long and valuable connection with the College is coming to an end. Besides being a most industrious and useful assistant in the administration of the financial side of the College, Mr. Keyes had served as associate editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE from 1907 to 1909 and as managing editor or editor-in-chief from 1910, in which capacities he did much to enhance the excellence of this publication at the time when it was taking definite shape and formulating its general policies of service.

Of his manifold activities in the college management it is hardly necessary to speak to any audience of Dartmouth alumni. Soon after graduating, Mr. Keyes became an instructor in English and an assistant professor of the fine arts. He served as secretary of the Alumni Association from 1912, and a year later assumed the new and extremely important post of "Business Director of the College," with the incidental duty of being secretary to the Alumni Council in that year. The growth of Dartmouth in size and scope created new and perplexing problems, to the solution of which Mr. Keyes brought a resourcefulness and sterling judgment which have been of the first importance to the financial side of the institution at that juncture.

No one who has had even the most casual knowledge of the work done by him will have failed to remark the curiously diversified character of his talents. It is unusual, to say the least, for artistic, literary and business ability to coexist- but coexist they do to a most remarkable degree in Mr. Keyes. All these gifts— and many more—have been employed without reserve to advance the prestige of Dartmouth and this MAGAZINE has received its full share. A special word of thanks and of Godspeed seems to de due and is herewith most cordially uttered.

When the much-discussed Professor Einstein gets away from the mysterious realms of "relativity" it appears that he is understandable enough. In speaking before the Princeton people, for instance, he made acute comment upon the trend and tendency of American collegiate education as manifestly toward the leavening of whole lumps with the yeast of letters, rather than toward the fostering of ripe scholarship in the few.

"I do not believe," said Professor Einstein, "that the atmosphere of an American college such as Princeton is conducive to deep study or concentration, as is the quieter, more restricted life in the German university centres. You have too much that is not study that attracts. Your sports, your social life, the constant intercourse between students, that does not make study. But your young men learn much from this. They expand. They have more chance for self-development. On your campus here at Princeton you have many things that fill much of the students' time outside of the classroom. You publish a daily newspaper, no university in Germany does such a thing. But the time so spent is not wasted; they learn much so. Your colleges here in America should make better men, but not better students."

It may not be so true as it was that the man emulous of a reputation as a savant has to obtain a degree at some foreign university, and it is likely to be several years before German universities in particular revive their former prestige among aspiring scientists in the United States. But it is quite true, as Professor Einstein says, that the American colleges do not aim at quite the same result as that which the ancient universities of the European continent have sought— and they have done this consciously, with open eyes and with what the lawyers might call "malice prepense" in some degree.

Our theory at Dartmouth, certainly, has been that the college would best serve its day and country by cleaving to the , idea of producing "better men" in large numbers, rather than by trying to produce a small and select body of profound scholars. It must be remembered that despite our Pilgrim tercentenary we are a young country, still more or less in the raw, growing more rapidly than is good for us, still facing the tasks of the political pioneer, and thus far devoid of that leisure which profound scholarship demands. Indeed, unless we have, sadly forgotten our Greek roots, the very word "scholar" implies a person of leisure. With the unfolding of the ages, no doubt, the United States will in due season become the seat of such specialized learning as hitherto one had to seek abroad. But for the time being we are a great and very new country, sadly in need of a very high level of general intelligence for the proper conduct of a democratic government —and this imposes an imperative duty upon the colleges to assist in raising that level with all speed.

Intellectual leadership is a thing which can be cultivated in comparatively tew, and those few gifted from birth. Leaders are born, not made—as poets are. What the colleges appear chiefly concerned to do is improve as far as may be the quality of those who are to be led— i. e., improve the intellectual and ethical perceptions of the great mass of young men and women. Our conditions differ widely from the conditions under which the "educational systems of both Germany and England were developed. It was Stevenson, we believe, who said that the British educational system was "better devised to train men for the prime minister's portfolio than for the tasks of the intelligent voter." He would hardly say the same of the American system and on the whole it is probably for the best that it is so.

Meantime it is to be noted that so erudite a journal as the Springfield Republican, whose opinions are certainly entitled to respect, inclines to the other view—so at least we interpret its critical comment on certain remarks of President Hopkins in which he upheld the theory that the best possible education for the mass of Dartmouth students should be the ideal. The Republican seems to adopt the theory that a college should play up to its most brilliant minds and let the average man trail on as best he may, treating as immaterial any sacrifice of the latter's interest that may be involved.

This topic has been debated long and apparently without reaching definite conclusions. There are still, and there will always be, critics to hold the view seemingly taken by the editors of the Springfield Republican. It seems probable, however, that this is the minority opinion and that it will continue to be such as long as the country's circumstances remain what they are. Possibly, since this democracy is likely to be enduring, the conditions will not greatly change even with the lapse of centuries so far as concerns the need of considering first and foremost the improvement of the average man. It isn't a case of what we might like, but of what we must have. The future, no doubt, may be left to care for itself. In the present we believe the case calls for the treatment indicated by President Hopkins —which is the development of the general theory so strongly emphasized by President Tucker in his day of personal direction in college affairs. Show us your man," was his reiterated test for the estimate of any college. He, in hr time, was similarly criticized for subordinating the scholastic ideal to the leavening of the large masses of the public by disseminating college training as widely as might be; but it seems to us more than ever before that he was right. Professor Einstein's comment merely proves that an unprejudiced observer finds the same condition and a similar theory prevailing in other important American colleges.

Those, of us who live apart from the cloistered and scholastic shade perhaps appreciate more than others can the pressing need for the promotion of a large and intelligent citizenship—not "scholarly" in the accepted sense, but at least possessed of a bowing acquaintance with the higher things and loftier ideals There is not nearly so much need for holders of world's records among our American intellectual leaders as there is for a live body of reasonably intelligent men and women everywhere. The advocates of the theory that colleges should play to their most brilliant minds and let the mass of students work out their own meagre salvation as best they can, seem more concerned for world's records than for a practical service of general character. This, so far as it is done at all, seems work for the very few—and the great number of American colleges with their wholesale appeal are debarred from it. At the most they will produce but few field-marshals of education; and they are, in fact, much more concerned to provide adequate subalterns—nay, i may better be mere non-coms—to steady the ranks. For our ranks of citizenship are vast and the need for steadying is prodigious.

Vice-President Coolidge, writing in the Delineator magazine, cites numerous examples of ultra-radicalism in the outgivings of college authorities, and deprecates the same with his usual terseness and good sense. He is by no means backward about mentioning names. Possibly the article in question was penned with more vigor and spirit because the writer was aware that, as governor of Massachu setts during the troubled days of the police strike in Boston, he reaped abundantly of the bitter criticisms of college radicals—althouugh for this .there was balm in the revelation that people in general indignantly repudiated the whole fabric of university bolshevism as it bore upon this episode.

This tendency toward a certain rudd ness of socialism is confined to no one college and of course is manifest in no one section. It is a universal trouble, which better balanced men and women have deplored and of which it is possible to exaggerate the important effect. Mr. Coolidge appears inclined to overrate the susceptibility of the mass of college students to what he hints is an' "insidious propaganda," conducted by socialists with the connivance and sympathy of the more radical faculty members. Our own feeling is that healthy-minded college men and women react against these propagandist notions precisely as the bulk of non-college men and women do. The record of the colleges in the war affords small evidence that the pacifists and anti-government theorists find in the undergraduate soil a fertile field. Some of the seed falls upon thin soil, springs up quickly —and withers away because it hath no deepness of earth. But for such disseminations we hope and believe that the great mass of college students will prove to be stony ground, in which these alleged propagandist sowings will find scanty lodgment.

It is true, however, that more or less difficulty has been experienced by the various colleges in canvassing for large endowment funds because of the indignation which alumni feel against the too vocal sympathies of a few vagarists in nearly every faculty. It is natural that "intellectuals" should be found in such circles, with all their wild tendency toward overstrain. What probably saves the situation is the college student's abundant sense of humor—the surest of all antidotes against this poison from the East Side and the Russian steppes.

By this time no doubt the world has said nearly everything there is to say about Mr. Thomas A. Edison's famous tests of collegiate sapience. The incident was a curious one and the result appears not to be altogether disheartening to the colleges, despite Mr. Edison's finding that "college men don't seem to know anything" because they have proved incapable of answering a set of specific questions. Mr. Edison is probably still convinced that college graduates are ignorant—and college graduates are probably still convinced that they are not. The general world, so far as one may judge by published comment, does not incline to condemn the colleges so severely and intimates that Mr. Edison's questions were poor instruments for the formation of an accurate judgment.

One comes back to that everlasting query as to what the colleges are supposed to do. Up to a certain limit they may be asked to fill the minds of youth with predigested information, which ought, in many cases, to be retained as ready knowledge for use at need. The human mind being of limited capacity in the average case, most of us retain but little of the things we have been taught with sufficient clarity to cause it to respond at our call. Professor Campbell, we now recollect, used to say of the mental processes involved in mnemonics that "we dismember what we retain in order to remember what we recall. This is a formula which we are proud to say recurs to us after nearly 30 years without effort —a triumph for the instruction we once received at Hanover. But while we possess this inheritance we find ourselves quite incapable of the same readiness in responding to the vast majority of Mr. Edison's queries. If most of us ever knew the answers to those famous questions we have utterly forgotten them by

now—and the bulk of them never entered into our purview in any case. Is the college man ignorant because he cannot answer the Edison questions? Certainly not—no more than Mr. Edison is ignorant because he probably could not answer a set of as many questions which virtually any intelligent person living could ask him.

Having said which, it may be fair to append the opinion that in Mr. Edison's list of questions there certainly were many which any college educated person, man or woman, ought to be reasonably well able to answer, but which, one regrets to believe, too many could not. To jump to the Edisonian conclusion that "college men don't seem to know anything" may not be justified however.

Most of the criticism of the list of queries has been based on isolated blocks of questions—chosen, it would seem, with a view to proving the whole list to have been equally absurd, which was not the fact. It is hardly reasonable to expect the ordinary mind to remember the rate of vibration of red and violet lightrays, or know off-hand what states are now inhabited by the Apache Indians. But surely there were easy questions enough and any college-bred person should be able to say something about Solon, Plutarch, Francis Marion, Fenimore Cooper, Thomas Paine and the like. Surely one ought not to be ignorant as to how and from whom the territory known as Louisiana was acquired. The list covered a very wide field and by no means all the questions were technical, or were related to obscure facts with which no one would charge his mind.

It is possibly pertinent to bear in mind the fact that the larger industries annually scour the colleges for promising young men; and within a month the writer was told by a leading New England newspaper proprietor that he made it a rule to take on no new member of his staff who had not received a college education. So the verdict, based on something broader than this single examination of the Wizard of Menlo Park, evidently is that college men aren't so ignorant after all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1921

August 1921 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNPROVABILITY OF MAN

August 1921 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

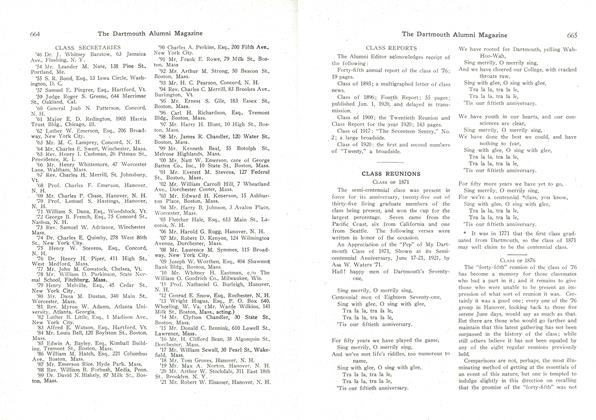

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1876

August 1921 By HENRY H. PIPER -

Article

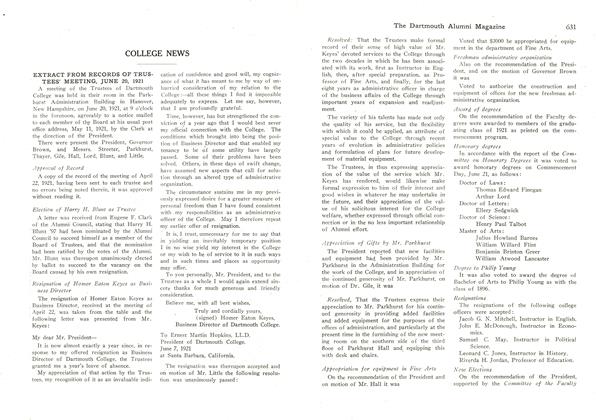

ArticleEXTRACT FROM RECORDS OF TRUSTEES' MEETING, JUNE 20, 1921

August 1921 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

August 1921 By N. G. BURLEIGH -

Article

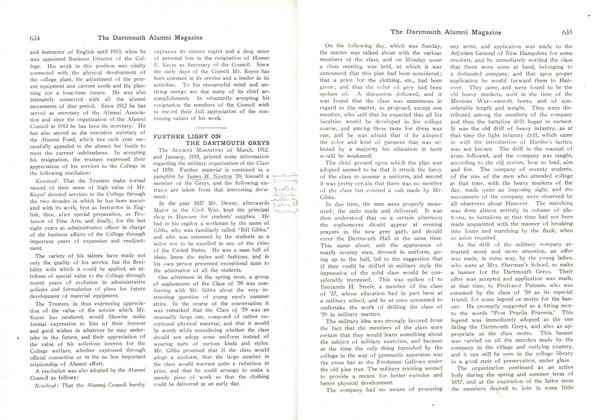

ArticleFURTHER LIGHT ON THE DARTMOUTH GREYS

August 1921